Sound Archives - A Guide to their Establishment and Development

Sound Archives - A Guide to their Establishment and Development

Edited by

David Lance

1983

IASA Special Publication No. 4

©1983 by the International Association of Sound Archives

ISBN 0 946475 01 6

Secretariat: Helen Harrison, Open University Library,

Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, England.

IASA Members may also download a free PDF version. If you are not a Member, why not join IASA?

Table of contents

Preface and Acknowledgements

The growth of new sound archives has been considerable during the past few years. Partly this is reflected within the International Association of Sound Archives which has seen its membership treble in the last decade. For these new members specialist advice can be gained from longer established member archives inside the professional community which IASA - as the only international body concerned solely with sound archivism represents. Through its journal (the Phonographic Bulletin), its special publications, its annual conferences and by the opportunities it provides for informal contacts, visits and exchange of information, the Association makes its expertise available.

Despite the fraternal availability of such professional benefits there are many regions, particularly the Socialist and Third World countries, in which IASA is not represented and where colleagues share problems which have already been experienced - and in many cases solved - within the International Association. Increasingly, new and inexperienced archives are therefore turning to individual IASA members for assistance. Thus, through these members, the Association has provided consultants whose work in areas such as Africa and South East Asia has furthered the development of sound archivism. Their role has often been confined to specific technical issues but, not infrequently, the question has arisen of how to establish an entirely new sound archive in an area without prior experience in the field. This 'Guide' is an endeavour to present in a general reference work the kind of basic information which many IASA members have previously provided through bilateral arrangements.

As the bibliographies in Appendix A of this publication illustrate, there is a considerable body of available literature on many of the specialised aspects of sound archivism and its related disciplines. Though widely scattered, much theoretical and practical information may be found which bears on the question 'How do you run a sound archive?' For institutions and individuals faced with the basic question 'How do you set a sound archive up?' there is, paradoxically, an almost total information vacuum. It is this question to which the contributors to this publication were asked to address themselves. As will be seen the individual authors have interpreted their brief in different ways; some offer fairly general brief in different ways; some offer fairly general in their advice. This work, therefore, should be seen as an introduction to sound archivism and certainly not as the last word. Readers are urged to make use of the 'Suggestions for Further Reading' in Appendix A to find sources of information relating to their detailed needs.

It is hoped that this guide will be particularly useful in Third World countries, where sound archives are a more recent interest and development. However, the publication is not exclusively designed for this purpose. Since the 'state of the art' in many developed countries is not high, it may be that this work will contribute to its general advancement. Much still needs to be done, however, before a body of reference material comparable to that which exists for conventional librarianship and traditional archive work will be available and the field of sound documentation adequately served. Towards this end IASA will shortly be publishing a Technical Manual and a guidebook on Selection. Further professional reference works may be expected within the next few years, to provide eventually the comprehensive coverage of sound archive techniques that is necessary.

In preparing the 'Guide' for publication I received valuable assistance. Bill Linnard, Grace Koch and Alexander Jansen - who are not otherwise acknowledged kindly provided the information on which the case studies for folklore and language, ethnomusicology and language, and commercial recordings in broadcasting are based in Chapter Ill. Helen Harrison and Dietrich Schuller gave advice and practical help in preparing and printing the work, while the eagle eyes of Laura Kamel and Kay Chee Lance spared me embarrassment from many errors and inconsistencies which would otherwise have been printed. Above all I must acknowledge the patience and tractability of my authors who tolerated with sometime astonishing forbearance the violence inflicted on their contributions by such an inexperienced editor!

DGL

1. Approaches to the National Organisation of Sound Archives (Rolf Schuursma)

1. Introduction

Sound archives have various origins. Broadcasting sound archives came naturally into being because of the primary need for developed storehouses of recordings for use in radio programmes. Other sound archives have developed within research or educational institutions which took up sound recordings as yet another source of information in their specialised fields (e.g. music, ethnomusicology, dialectology, political or social history). There are many and varied examples of such specialised archives, ranging from the Department of Sound Records of the Imperial War Museum in London to the Ethnomusicology Archive of the University of California in Los Angeles, and from the sound archive of the Netherlands Theater Institute in Amsterdam to the audio collection of the Indian Classical Music Foundation in Bombay. Many other archive$, however, developed inside institutions responsible for general collections, frequently of a national or regional character, which do not accentuate any specialised field. Thus centres like the Library of Congress in Washington DC or the Public Archives of British Columbia in Victoria have gradually built up extensive collections of sound recordings of spoken word and music alongside collections of books, documents and other media. A few sound archives have come into existence simply because their founders wanted to concentrate on sound recordings as such, regardless of any particular subject or regional interest, and independent of all other media. The British Institute of Recorded Sound in London is perhaps the best known archive of this kind.

Although the categories described above represent the main stream of sound archive activity other types of audio collections are also to be found. There are, for example, lending libraries which primarily specialise in the distribution of published material such as audio discs and cassettes and there are scientific institutes where sound recordings may form part of their monitoring or experimental data (e.g. recordings of the heartbeat made for medical purposes or bio-acoustic recordings used in the study of animal behaviour).

Whatever their origins, however, developments so far give the impression that in many countries sound archives - outside the realm of broadcasting – have been established as a consequence of momentary needs and certainly without much preliminary deliberation about an overall structure of sound archiving on a national scale. Even in areas where some effort has been made to consider whether the establishment of one or more sound archives would best meet the needs of the country as a whole, the outcome has seldom if ever been a structure based on clearly defined and elaborated possibilities and priorities. Some people may argue that this kind of 'structural' course is apt to fail and that a more ad hoc establishment of sound archives provides a stronger and more flexible approach to national needs than any other policy.

Whichever conclusion may be reached, however, it is important that the issue should be seriously and systematically considered. In many countries without any kind of sound archive organisation audio collections of various kinds are nonetheless coming into existence. The first requests for funds to cover their financial needs enter government offices or private foundations. Once this happens the administrators responsible for public or private money may, without adequate guidelines, grant or refuse resources according to the feelings of the moment. They should, however, consider the national need for sound archives and base their decisions on the outcome of such a study, while bearing in mind also the main existing models and options that are available to them.

2. General principles

In countries with as yet little or no sound archival activities there are two main ways of considering the subject, at least in theory. One is to look at sound archivism from the point of view of the medium itself, the other is to consider it from the point of view of the contents carried by the medium. The differences between the medium centred and the content centred approaches need further explanation before their respective advantages and disadvantages are examined.

The medium centred approach starts with the assumption that the preservation of sound recordings is so important and so specialised that the needs of the medium take priority over any other consideration. An archive based upon this assumption will tend to collect as many recordings as possible in order to preserve and describe them professionally and thus save them for posterity. Also such an archive does not usually give priority to research based upon the content of recordings and of other media carrying the same kind of information. The situation is reversed in the case of a content centred approach. Here the medium of recorded sound is just one instrument among many for research or education. It is the content of the recordings, which contributes to the total amount of information available for a given research or educational field, that is the centre of attention.

Anyone who is familiar with the field of sound recordings will immediately recognize that a strict differentiation between these two types of archives would be an over-simplification. In reality nearly every archive is a mixture of the two types with some accentuation of one or other of the two approaches. It is, for instance, obvious that no archive of the first type will totally neglect the contents of its recordings, while no archive of the second category will completely ignore the needs of the medium. However, this broad distinction is helpful for considering a national strategy for sound archives particularly in countries where as yet little or nothing has been achieved.

3. General versus specialised archives

Bearing this distinction between medium and content centred archives in mind let us first consider the needs of countries where recordings, of folk music or oral history for example, are coming into existence without being collected, preserved, described and made available in a professional way. In such countries there is much to be said in favour of creating a sound archive on a national basis which concentrates its primary efforts on the acquisition, the preservation and the description of every kind of sound record. Such an archive may conveniently be part of a national library or a public record office of written documents. The national institution would then take professional care of the preservation of the sound recordings in its collections, in the same way as it would of its paper and other records.

Although its staff would not perhaps spend much time on research on the contents of the records themselves, such a national archive would - in addition to preservation - certainly concentrate its efforts on their description, so making them fully available for research and educational purposes. If a national collection of sound recordings can be organised in this way as part of a state institution, then the government may also be expected to take care of its funding. In large countries additional centres may also usefully be established as branches of the national archive so as to provide recordings and facilities on a regional basis.

However, the national sound archive model has its limitations which should also be seriously considered before any conclusions are drawn about the most effective method for the organisation of sound archives. Every national archive is likely to try to live up to its broad objective by acquiring as many recordings as possible and to function as an archival centre for the total acquisition of every kind of sound recording in the country. However, unless the archive is part of such an enormously resourced and highly differentiated institute as the Library of Congress, even national archives will nonetheless generally tend to concentrate on a restricted range of subjects and be forced to leave some others aside. Although they are institutions with a wider field of view than is usually found in specialised archives the range of a national archive is still limited. The aperture of its lens has a wide-angle but nevertheless is not able to cover 360º or even more than 180º of the whole field of knowledge. This is not a situation which can be changed just by raising more funds and employing more staff. It is a structural problem, encountered in every institution where people try to cover comprehensively all fields of knowledge.

A related problem is that national sound archives will be required to administer a wide variety of highly specialised recordings many of which need much more detailed treatment than conventional cataloguing in order to make them most accessible for scholars. In this respect they are to be compared with public record offices and like those archives of written documents they seldom have the range of expertise to succeed in really giving their attention equally and on an equally high level to every subject of interest covered by their collections.

What then of the alternative approach to sound archive organisation: the specialised, single subject and content centred archive? From the point of view of the researcher and the educationalist a sound archive specialising in, say, history may be a better solution than a national archive, especially when it is part of a larger institution whose collections also include books, periodicals, films, photographs, written documents and newspapers relating to the same field. In other words, where all media combine to give maximum service to the user, who wants to study his subject of research or to have access to material for the class-room regardless of the medium it may be found in. This so-called multi-media approach is probably only possible in specialised institutes with archives concentrating on one field of interest or, perhaps, in some very great national institution like the Library of Congress.

A specialised institute with collections of pictures and sound recordings next to collections of printed or written records must, however, be prepared to direct a relatively greater part of its total budget towards the audiovisual media, for the obvious reason that the acquisition and the preservation of such media are generally more expensive than is the case with written or printed records. Such financial discrimination in favour of audiovisual records is not always achieved. Institutes with low budgets may easily feel that audiovisual media do not warrant such a high expenditure and decide to make less funds available for their administration than is professionally necessary. This is a problem for multi-media institutes and it can only be corrected or forestalled by firm decisions concerning the allocation of available funds.

There are other problems which must be taken into consideration as far as the specialised, single subject, content centred archive is concerned. One concerns the financial situation as seen from the national level. In the case of rather small collections, dispersed over several institutes, each specialising in different fields of research or education, the total cost may be rather high by comparison with the funds necessary to run a single, centralised sound archive which keeps all types of material on its premises. One should, of course, never accept such statements without applying a detailed cost-profit analysis but the assumption seems to be credible enough. Another major problem is that even a widespread network of specialised archives may not be able to cover the entire field of sound recordings.

Two institutions respectively covering folklore and ethnology, for example, may not have any activity in the field of dialect nor any interest in its development and, as a result, a major gap may be left in the national holdings.

4. Alternative models

Having considered a few arguments in favour of both national and specialised sound archives, it might be interesting to take a quick look at three other organisational models. First, the Arkivet för Ljud och Bild in Stockholm is an example of a national archive for sound recordings, videotapes and films, partly based upon the fusion of a few already existing archival collections. This Swedish model, of one integral national archive for all audiovisual media, is also interesting because it presents an alternative to both the national sound archive philosophy and the concept of audiovisual archives as part of a multi-media national institution like the Library of Congress. In Stockholm, sound recordings and moving pictures are brought together to the exclusion of other media such as books and written documents. It should be remembered, however, that storage and particularly the preservation of audio and visual media are in many ways different from both the technical aspects and from the financial needs and there may be some disadvantages to combining them. Also, in such an arrangement, the sound archive will only profit as long as the budget is fairly divided between the media, with each safely secured against interference, and so long as the management does not pursue a biased policy favouring the visual media at the expense of the audio.

Secondly, in order to profit from a similar kind of centralisation of the preservation and storage of recordings, several institutes in the Netherlands have proposed to the Government the establishment of an organisation which would act as a central depot and a clearing-house for audiovisual media and would also fill an intermediary role between the Netherlands Broadcasting Foundation (NOS) and the various public organisations and groups interested in access to radio and television material. These plans are primarily intended as a solution to the problems concerning films and video-tapes but they will undoubtedly have far reaching effects in the field of sound recordings as well. The clearing house idea may perhaps prove to be a valuable kind of compromise between the rigid centralised structure of a national archive and the 'anarchy' of quite independent and divergent specialised archives, especially in countries where such archives already exist.

Thirdly, there is the unique approach of Austrian sound archives united in the 'Arbeitsgemeinschaft Öesterreichischer Schallarchive AGöS' (Association of Austrian Sound Archives). The AGöS foresees a few primary archives concentrating on the collection and preservation of original sound records. These archives should not be open to the general public, but a network of other institutions including libraries, mediathèques or audio-visual centres should act as distributors of copies of the sound records preserved in the primary archives. The AGöS considers it necessary to maintain content centred archives in this range of primary archives, also distributing their recordings through the network of regional institutions mentioned above. The system starts of course from the assumption that certain standardisations in the field of title description and distribution media have first been accomplished.

5. Factors affecting national patterns

In reviewing the models considered in the preceding pages it will be seen that, despite the existence of several variants, the broad choice to be considered for the national organisation of sound archives lies between the establishment of a single centre or of several. In choosing between the unification or the multiplication of sound archives there are three other major factors that have to be assessed before the balance of advantage can be finally judged.

The first consideration, already touched on, applies mainly to countries in which specialised archives already exist. Once a collection of sound recordings is part of a specialised institute the creation of a single national collection is likely to become much more difficult to achieve. There will be a natural reluctance among such institutes to give up their sound archives despite any practical arguments in favour of a central or national solution. The effectiveness of such a solution then also has to be weighed against the value and efficiency of the service which existing archives are already providing. The inevitably disruptive effects of ending their independence obviously has to be more than balanced by the benefits that can be achieved through their amalgamation.

Secondly, an important part of the sound archival resources of most countries is represented by the output of their radio and television organisations. The national pattern chosen for sound archives may be significantly influenced by how these resources can best be organised in any particular state. Although broadcasting organisations commonly maintain their own archival collections, these are seldom open for educational and research purposes. Thus separate arrangements will generally be needed to provide public access to such material. Given the complications of copyright and contractual obligations, broadcasting organisations are often reluctant to provide copies of their recordings for use outside their own premises. They will certainly be even more hesitant if they have to deal with several institutes, each putting forward its own demands, than if they only have to collaborate with one. From this point of view a national sound archive can usefully function as the sole agent for broadcasting collections of sound recordings, providing a suitable access point for non-broadcasters while also centrally controlling and safeguarding the rights of the broadcasting agency and its contributors. A further advantage of such centralisation is that it ensures public availability of all broadcast recordings, including those which may happen to fall outside the orbit of existing specialised archives.

Thirdly, a similar case for a national sound archive can be made in respect of commercial discs and tapes published by recording companies. The reluctance of the recording industry to sustain a proliferation of centres holding copies of archival material in which commercial companies own rights is indeed now confirmed by its official policy. Thus its agent, the International Federation of Producers of Phonograms and Videograms (IFPI), has begun to promote the establishment of national archives in its member countries to serve as the only intermediary archives between the recording industry and the general public.

Such a centralised arrangement for broadcast and commercial recordings may not, however, always be the best one for researchers. Most national archives are - as mentioned before - in fact specialised in certain restricted areas of research. In acting as central intermediaries between broadcasting organisations or recording companies and researchers, however, they would also have to deal with many other fields of interest in which their staff may have no specialist knowledge. The BBC, for example, has understood this problem very well. Thus, copies from the large and valuable collection of recordings made during the Second World War have been made available to the Imperial War Museum, specialised as it is in that field, and not to the British Institute of Recorded Sound, which serves as a national sound archive but does in fact concentrate primarily on the field of music. As a matter of course any general archive might be expected to handle the BBC Second World War collections at a lower level of description and research than the specialised staff of the Imperial War Museum.

To conclude, the problems of and the models for the national organisation of sound archives are manifold and it would be unwise to pretend that there is but one solution for every country developing activities in this field. However, the establishment of a national sound archive is in many cases the best safety net for the recordings which every country is producing in ever greater amounts. This will ensure that all kinds of recordings will find their way into a professional preservation and description centre, where at least they may be saved for the future. Eventually specialised archives may also come into being, but even then a national archive may continue to fulfil this central function while also preserving those recordings which would not be collected elsewhere.

2. The Technical Basis of Sound Archive Work (Dietrich Schuller)

1. Introduction

The wide-ranging scope of this book illustrates the great variety of disciplines and institutions which owe much to sound recording or archives for their essential stimulus. Indeed, without sound recording and sound archives, it would be hard to imagine some disciplines ever existing in their modern form. Although the problems peculiar to each individual subject are and will remain the prime concern of scholars in those fields, all need to consider the basic technical requirements and the physical conditions necessary if acoustic source material is to be produced and to remain unspoilt for posterity.

This chapter, therefore, is aimed at the technical layman - such as the scholar drawing up a research programme or planning a sound archive - so that he might have some idea of the technical and financial implications of his plans and to ensure that, from the very beginning, he seeks the co-operation or at least the constant advice of technical experts. 1

If we are to establish what problems have to be overcome in sound recording and sound archives, we must first know something about the nature of sound itself. The term 'sound' is generally understood to mean periodic oscillations in air pressure, but for our purposes (with the exception of some bio-acoustic matters) it is sufficient to consider sound simply in terms of human hearing. In humans, hearing sensitivity starts at 16 cycles per second (Hertz, Hz) and extends to an upper limit of 20,000 Hz (20 kHz). Each doubling of audio frequencies is called an octave and the range of human hearing covers about ten octaves. With regard to different sound levels, human hearing has an extensive range. Hearing sensitivity begins at a sound pressure level of 2.10-4 micro-bars and extends to as high as 6.102 micro-bars, at which point the sensation of hearing becomes painful. The ratio of these sound pressure levels, which we term the 'dynamic range', is about 1:3,000.000 or l30dB2. All acoustic phenomena, whether a tone, a sound, exotic music, speech or any sort of noise, are made up of quite individual patterns of oscillation each of which can comprise a variety of partial oscillations but which can all be expressed in the fundamental parameters of frequency (= cycles per second or Hz) and amplitude (sound pressure level, expressed as dB).

By a transformation process, sound recording has to convert these parameters into a medium in which the function of time is rendered as a function of space, i.e. every moment in a sonic event has to correspond to a particular point on a recording.

Old phonographs and the early gramophones used to do this mechanically. Vibrations in the air were captured in a horn, exciting a membrane which in turn set in motion a stylus which left modulations on a revolving cylinder or plate, each modulation corresponding to the vibrations of the membrane and the air. The process of reproducing the sound simply involved reversing the procedure. The modulated groove moved a needle which then caused a membrane to vibrate and the vibrations would be amplified and made audible by the horn. In time electronic methods of recording and reproduction came to be used; the air vibrates the membrane of a microphone which then transforms the vibrations into an analogous alternating current. After precise amplification, this drives an electric cutting head. In reproducing the sound, we nowadays use electro-dynamic or electro-magnetic sound pick-ups which convert the modulation of the record groove into an analogous alternating current. By means of an amplifier, this will then drive a loudspeaker or headphones, which convert the alternating current back into air vibrations. The disc itself has not changed in principle since it was originally introduced.

In magnetic sound recording, the sound is stored on a magnetic tape. The alternating current from the microphone is converted in the machine's recording head into an alternating magnetic field. The tape, moving at a constant speed across this recording head, has each particle stored within its coating re-arranged in accordance with the alternating field. To reproduce the sound, the magnetic field fixed on the tape produces an alternating current as it passes across the replay head and, suitably amplified, is converted into sound by the loudspeaker. The process functions that much more precisely the more linear the system or, to put it another way, the less distortions there are. These distortions can be classified as three different types:

- Linear distortion: this is caused by uneven sensitivity at different frequencies. The ideal requirement is a flat frequency response i.e. constant sensitivity across the whole audible range, from about 20Hz to about 20,000Hz.

- Non-linear distortion: this is caused by changes in the original wave form and appears as spurious sound not present in the original (harmonic distortion, intermodulation distortion).

- Modulation distortion: distortion mainly caused by irregularities in the tape travel. Pitch fluctuations ('wow' and 'flutter') and 'mod-noise' come under this heading.

In addition to these distortions there is the unavoidable noise which we find in every link in the chain and which occurs particularly in the sound carrying medium itself, limiting the dynamic range which can be stored. Despite all the technical progress which has been made since sound recording was invented, there is still no system so perfect that distortion will not occur. Even though there are no difficulties nowadays in converting and storing the whole audible frequency range, non-linear and modulation distortions are still with us. More important, with analogue recording techniques only 60 of the 130dB dynamic range of human hearing can be stored (although with the introduction of digital technology the upper limit of this can be raised to 96dB).

In view of what we shall see can be quite considerable outlays for machinery, servicing, tapes and their care and storage, we must explain why this cost-intensive standard is necessary for sound recording and archiving. In contrast to the written and printed word which reproduces a verbalised mental process by a series of representational symbols, a sound recording documents a physical event which can be repeated at any time after the event itself. A certain amount of redundancy is intrinsic in speech and writing and - without any real detriment to communication - letters, words, even whole clauses can be omitted. The essential value of a sound document, however, lies in the very information which it supplies over and above what can be transcribed; such as form and variations in tone, manner of speech, or - in the field of music - the timbre, the performance, the subtleties of rhythm. Here, too, we see more clearly that musical notation provides no more than a framework, just a small part of the total musical message. In the case of a noise, however, written symbols cannot provide an adequate substitute for any part of a sound recording. It is the very information which a transcription simply cannot convey, which provides the criteria and the fundamental argument for high quality sound recording. If, for any reason, the additional information supplied by a sound recording is considered worthless, then the recording is no more than an intermediary substitute for a written record and is not worth keeping. Merely making a voice intelligible or a melody clear enough to be transcribed should not become the sole criterion for technical standards in sound recording. Rather, it should ideally be a question of exhausting all available means to obtain the optimum quality of recording. The value of this ideal is further underlined by the fact that more and more scholars in various fields (musicology, linguistics, psychology) are endeavouring to make this element in sound recording which transcends writing, a subject for serious research.

It must not be concluded, however, that an ideal recording technique will necessarily produce an ideal recording in practice, for an array of technical gadgetry may end up distracting and disturbing the subject being recorded. Careful consideration must be given in every case to producing a compromise between the requirements of technical precision and the need for equipment to be unobtrusive, together with all the implications this may have for the choice of equipment and the resulting recording standards.

The question as to whether existing historical recordings are worth retaining despite their technical shortcomings is something which must be decided after consideration of the contents in each case, but a decision to retain them should not lead us to the conclusion that we may abandon the idea of trying to obtain the highest possible standard of recording in new projects.

- The Technical Committee of IASA is preparing a Technical Manual for Sound Archives which will deal in depth with all the technical problems specifically related to archives and will be aimed at a technical readership also. As this chapter is only meant to serve as a basic guide, it does not go into detail and deals only with conventional analogue recording techniques. For more detailed information, readers should consult the literature listed in the bibliography to this chapter.

- dB (decibel) is logarithmic ratio measurement of sound pressures or its analogous voltages.

2. Choice and maintenance of equipment

In all areas of making original recordings and producing archival copies, the use of equipment of a professional or, at the very least, semi-professional standard is vital. By professional equipment we mean the sort which comes up to modern standards of technology, which will guarantee a minimum of distortion and which will be sturdy enough to continue producing recordings of the highest standard after hundreds and even thousands of hours of operation. By semi-professional equipment we mean the sort designed for the discerning amateur which, in its technical performance, will almost if not totally equal that provided by professional equipment. Of course, semi-professional equipment is not as sturdy in its construction as the professional variety and its performance will decline after extensive use.

Above all, these basic principles apply to the tape recorder which is the vital organ of the technical system in all modern research programmes. If it is at all possible financially, both stationary and portable equipment should be of the professional kind. In view of the small number of companies which deal in equipment of this class, and of the comparable price-to-performance ratio of different products, the choice of a specific make is not critical. From the point of view of efficiency, however, it is best to choose a manufacturer with outlets across the country or throughout the region as this will make servicing and the supply of spare parts that much easier. This generally means using the makes and types of equipment used in local or national radio stations. This approach is particularly recommended for countries outside Europe, if one is to avoid the risk of recording sessions being held up for several weeks when equipment breaks down. Of course, semi-professional equipment can also be used for recording but any savings on purchase costs must in the long run be offset against higher outlays on servicing and repairs. However, these cheaper types of equipment may be used in cases where less precise copies of high quality recordings suffice, such as in monitoring. 1

Of all audio equipment, the tape recorder requires the most thorough maintenance. This is because each individual machine has to be very carefully tuned to match the tapes compatible with it, if the optimum performance is to be obtained from both together. With continuing use the tape heads are gradually worn down, impairing the performance, and regular adjustment is absolutely vital if the best possible quality is to be retained. Moreover, electrical parts can, without any warning, become defective regardless of how long they have been in use and it is essential that tape recorders and the adjustments made for the tapes used on them should be continually monitored. In general, the following service schedule might be used as a reasonable guideline for professional equipment:

Daily (or every time a machine is used): check the frequency response and carry out an auditory test.

Weekly: clean and demagnetise the tape heads and tape paths.

Two monthly (or after every 50 hours use): carry out a full service.

In the case of semi-professional equipment (especially with machines which receive rather rough handling or are used to record a unique or rare occasion) it is advisable to carry out the above procedures at more frequent intervals. A full service on a professional piece of equipment will take between one and two hours (as long as no serious repairs are necessary) but about twice as long is to be spent servicing a semi-professional set. If it is at all possible financially, institutions should employ their own well qualified audio service technician for this work. Even if an institution has only a small amount of equipment such a technician, qualified in the right field, can be given the job of producing copies and looking after the collection. In this way institutions will avoid the need to rely on the often shoddy workmanship of servicing firms and at the same time find it easier either to carry out or to supervise the extensive servicing of equipment necessary in order to maintain archival standards. A written record should also be kept of this work. Managing all this, of course, requires a whole series of test apparatus and tools and, last but not least, a workshop.2 Lack of the necessary financial resources or shortage of skilled technicians may make this impossible, in which case one should always try to work in close co-operation with similar institutions which share the same service requirements and with whom a solution to one's needs might more easily be achieved. Alternatively, one might enlist the help of local or national radio stations.

Microphones should be chosen with great care. Not only do they have to satisfy specific technical requirements, they should also be tested in a properly equipped workshop whenever they have been extensively used (once a year at least and whenever they have been dropped or similarly mistreated). Here again, if the necessary facilities are not otherwise available, institutions of a similar nature should work together or, where there are no other similar institutions, radio organizations should be consulted for technical expertise and advice.

- Price ranges for tape recorders (¼ inch tape, mono or stereo, prices and exchange rate as of June 1982) are as follows. All prices quoted are in US dollars, ex-works, excluding import duty and taxes.

Stationary professional sets .............$ 3,500 to 8,000

Stationary semi-professionals sets ...$ 1,000 to 2,000

Portable professional sets ............... $ 4,000 to 6,000

Portable semi-professional sets.......... $ 600 to 1,000

- For the range of essential measuring devices and equipment one should be prepared to pay at least US $3,000.

3. Choice of tapes and tape formats

If the highest standards are to be maintained, then the choice of tapes and tape formats is scarcely less important than the choice and maintenance of recording equipment. Because of its sturdy nature and its low sensitivity to humidity and temperature, and because it presents the least mechanical problems, the tape most widely used nowadays for archival purposes is polyester tape with a thickness of 52 micro-metres (1.5 mil). Several varieties of tape display good electro-magnetic qualities, are not significantly prone to print-through and are, therefore, suitable for archival purposes. For recording outside the studio long-play or double-play tapes are often the best sort to use because of the length of recording time they give, but care should be taken to make sure that these records are transferred to archival tape as soon as possible. It is impossible to say that anyone particular tape is 'the best', and the choice of tapes is usually a question of compromise between availability and price. As with the choice of equipment, one should bear in mind when choosing tapes, how many other similar institutions or radio stations use the same type. Furthermore, one should generally choose tapes which are likely to be available on sale for as long as possible, so that recording equipment does not have to be continually re-adjusted to compensate for different sorts of products. For the same reason it is advisable to purchase a large stock -about a year's supply -in advance and to ask for a batch from the middle of a production run. Care should be taken with new varieties of tapes, as the improved electro-magnetic qualities of a tape can often be accompanied by a fall-off in mechanical quality (such as its resistance to oxide shedding), at least during the period when a new tape is being brought onto the market. It makes better sense, therefore, to choose a somewhat older but proven product rather than risk losing valuable source material by using poorly tested products.

As efficient sound recording is a basic requirement for sound archives, it follows that high standards should be observed when choosing tape formats. The recording speed for original recordings and archival copies should never be less than 19 cm/s. For mono recordings one should use full-track, while for stereo recordings, halftrack should be used. For evaluation work and for distribution the expense can, of course, be tailored according to the requirements and for certain types of work compact cassettes are quite adequate in the quality they provide.

4. Handling, storage and preservation

In presenting the arguments for high standards in recording we saw that sound recordings, unlike written records, contain no superfluous matter but that every detail is a source of information. In a book, a spot of fungus on a page will generally not hinder the reader and at worst may reduce the volume's commercial value, but the slightest damage to a sound recording immediately results in a loss of information. Its physical vulnerability dictates the precautions which we need to take if we are to ensure the preservation of acoustic source material. 1

Before considering other risks to sound carrying media we must first consider the problems of decrease in quality as a result of normal use. Disregarding the damage done to recordings by careless handling, the loss of quality through normal use is relatively high in the case of mechanical sound carrying media. Because of the friction between stylus and record, with time the groove becomes worn and the signal distorted. The degree of wear and tear involved depends on various factors, but above all on the condition and adjustment of the record player. The recorded signal and the material of which the record is made are also important factors, so that no matter how careful one might be the risk of damage can still be relatively high. These risks are appreciably less in the case of magnetic recordings and, provided excellent playback facilities and modern tapes are used, it is safe to say that changes in the signal in normal playback will be minimal. There is always the danger that tape oxide might sometimes be rubbed off, especially when older tapes are wound at high speed. In particularly bad cases one must take special care by making safety copies, but generally it is sufficient simply to wind at a slower speed.

The effects of temperature on sound carrying media depend on the material involved. In the case of shellac and modern vinyl records and the nowadays rather rare PVC tapes, temperatures above 500 C are considered a risk. The old acetate tapes, which are no longer produced, and the modern polyester tapes can withstand temperatures well over l000C. High temperatures, however, will increase print-through on tapes and continual changes in climatic conditions are also to be avoided; the optimum temperature for an archive is 200 ± 30 C, although print-through can be kept to a minimum in rarely used stores for security copies by keeping temperatures at a level of 100C. It should also be noted that heating devices, lighting and sunlight can also be damaging, even when temperature controls are used. The field researcher operating in tropical climates can provide some protection for his tapes and films by keeping them in polystyrene containers.

Only shellac records are immediately at risk from high humidity. The old acetate and cellulose tapes, on the other hand, shrink and warp if storage conditions are too dry. Micro-organisms such as fungus thrive in high humidity and quickly attack both magnetic and mechanical sound carrying media altering the surfaces to such an extent that the record content may be partially or even totally ruined. Relative humidity should therefore be kept to a level of 50% ± 10%. Humidity is particularly important to researchers working in tropical regions, where valuable original recordings can be protected by frequently exposing them to the air and storing them together with moisture absorbent silica gel.

On records, dirt in its many forms produces the well-known crackle effect. With tapes it leads to 'drop outs', as the contact is lost between tape and tape head. Dust should, therefore, always be avoided and, equally, one should never touch the surface of a record or tape as this can also cause dirt to stick to it. Adhesives of all kind, especially inadequate splicings, should be removed if present and otherwise generally avoided. Before adopting a particular method of cleaning record or tape surfaces, one should always make a thorough check of the available literature on the subject and test the methods properly beforehand. Good packaging, properly sealed work rooms, archive areas which can be easily cleaned and with dust filters fitted to climate controls should provide a good protection against dust.

Defective spools and uneven winding can cause tape warping as also can bad packaging and incorrect storage. Both records and tapes should be stacked absolutely vertical when in store; if they are kept in a leaning position for long periods, they can become permanently warped and so this too should be avoided. Records may also be stored in suspended position, while any inserts - such as textual material - which can cause them to warp, should be kept separately.

A well-known and, as we shall see, over-rated cause of damage to tapes in store is the occurrence of print-through. This term is used to describe the echo effect resulting from magnetic interaction between two adjacent layers of tape on a reel, thus producing the effects known as pre-echo and post-echo. The degree of print-through mainly depends on the characteristics of the individual tape, on tape thickness, temperature and period of storage. However, the echo signal - unlike the basic recording signal - is unstable and can easily be greatly reduced by mechanical means, such as rapidly rewinding the tape. This is confirmed by the results of recent tests. 2 The problem of print-through, therefore, is one which can be ignored as long as tapes are chosen and stored correctly, are rewound once a year and kept alternately on the take-up spool (or 'tails out' position) and the feed spool (or 'tails in').

One should not underestimate the dangers to tapes from magnetic fields. Tapes should, therefore, be kept well away from dynamic microphones and headphones, as well as from loudspeakers and electronic measuring instruments. Permanent magnetic fields, which are a particular risk to tapes during play-back, can also build up on tape heads and tape guides. Regular demagnetisation is, therefore, a vital part of any service schedule. One should also make certain when fitting out storage areas that there are no high voltage electricity cables, power transformers or lightning conductors in the vicinity which might be dangerous sources of magnetic fields.

To complete the picture, it must also be said that one should consider not only the specific problems mentioned above, but also the more general ones such as security against theft, fire and flooding.

- Because this chapter is only meant to serve as a basic guide, only the most important sound carrying media have been mentioned. These are:

Mechanical recording media (records):

shellac records (78 rpm records)

vinyl records (LP records)Magnetic recording media (tapes) with the following base materials:

acetate-cellulose (AC, no longer used)

polyvinylchloride (PVC, rarely used)

polyester (PE)

- Schüller, D. 'Archival tape test' in Phonographic Bulletin, No. 27; 1980

5. Conclusions

As we have seen, all forms of sound recordings are extremely vulnerable and we should, therefore, consider a few basic principles and organizational methods aimed at minimizing the intrinsic problems involved.

Even if all the measures mentioned under section 4 are observed, accidental damage can never be ruled out. It is, therefore, necessary to develop a policy which will minimize - if not eliminate - any remaining risks. The main principle of such a policy is to keep -if at all possible - two high quality copies of each item in separate locations: one in the storage area of the sound archive itself; the other in a security vault well away from the archive's premises.

Wherever original recordings are made in a studio, standard archival tape should be used. Ideally two recordings should be made at the same time: one should function as the archival master to be retained in the archive itself. The second should function as a security copy to be stored in the security vault. The archival master should only be used occasionally, while in those cases where frequent use or in-depth evaluation is foreseeable, an additional (working) copy should be made. This copy may be of lower fidelity and even a cassette copy may serve for many routine archive purposes.

Original recordings made on portable equipment in the field, are rarely recorded on standard archival tape. It is therefore necessary to copy these long-play or double-play original tapes onto archival tape which then will serve as archival masters. If economies have to be observed then as a compromise the original tapes may, after copying, function as security copies, although it must be borne in mind that LP or DP tapes are not the most suitable for security purposes.

The production of archival masters and security copies should always be done with utmost technical care avoiding any element of subjective filtering or other aesthetic treatment. Fast copying techniques always affect the quality and therefore should be used - if at all - only for the production of working copies where a lower quality is acceptable. Every archival master tape should begin with test tones which facilitate the production of further copies and make it possible to conduct subsequent quality control inspection of the tapes. They also serve for short checks of the equipment while it is used. 1

The same principles of security also apply to records. Duplicates should be kept and - for security purposes - be stored at separate locations. Because of the higher vulnerability of records, the archival master should always be a tape copy while the record itself should only be used if the archival master is accidentally destroyed.

All storage areas, the one in the archive itself as well as the separate security vault, should be equipped with full temperature and humidity control (especially under tropical and subtropical conditions). The high cost outlay involved will often suggest co-operation with other sound archives in the same country or region. It may, therefore, be wise to establish as few independent sound archives as possible and to concentrate financial resources as well as organizational and technical skill. At university level, at least, only one unit should be established and professionally equipped and this should maintain co-operation with all research bodies that have an interest in the production and use of sound recordings.

If proper technical quality control is to be maintained, then written records should be kept of all equipment used for recording and copying. A note of the dates on which the recordings were made and the results of tests conducted should also be kept. This information together with the written reports on equipment tests, make it possible to carry out proper quality evaluations of copies. This is especially important in the light of the increasing work being done in all fields in acoustic analytical evaluation, since a sound recording essentially provides a measurement of a physical process whose accuracy or inaccuracy has to be known. It is also useful to keep test reels of each of the various sorts of tapes or batches of tape used, with recorded signals and a length of unused tape for future inspection and test.

Finally, it should be a basic principle of routine organizational security that only archival staff be allowed to handle original tapes, archival and security copies. Only by strict observation of this principle and by careful choice of staff who believe in precision in all things, can damage to the archival holdings be minimised.

In this chapter we have tried to show the technical layman who has to produce, accession and evaluate sound recordings the basic physical and technical framework within which he must operate. He should not assume that he no longer needs to study the relevant literature or seek technical advice. This chapter, however, should help him to take the right direction from the beginning and to approach the responsible financial authorities for the necessary funds. Let us not forget that, amidst all our considerations, it is the physical preservation of valuable acoustic source material and an irreplaceable heritage which is at stake.

- Schüller, D. 'Standard for tape exchange between sound archives' in Phonographic Bulletin, No.19; 1977

3. Documentation (Roger Smither)

1. Introduction: why document?

Few, if any, established archives can truthfully claim that the documentation of their collections is satisfactory or adequate. Most will admit to a sizeable backlog of material which is at best poorly catalogued or at worst completely uncatalogued. Older archives will attribute such shortcomings to the failures or faulty priorities of previous generations of archive keepers, but enquiries about their current practice will often disclose that the backlog is not shrinking, and may not even be static. This state of affairs is also common to many archives created too recently to have previous generations of administrators to whom blame can be attributed. The truth is that it is not only in the past that cataloguing and record-keeping generally have failed to be accorded a high level of priority in archives' policy.

The reasons for this are not difficult to find. The task of cataloguing is undramatic, its only urgencies are self-imposed, and its visible benefits on the whole are unspectacular and slow to materialise. Large backlogs of uncatalogued material, after all, have not inhibited the survival of archives into the present. An archive that is not growing, an archive whose collection is not being used by its intended audience or customers, and an archive whose collection is deteriorating are all in different ways obviously failing. An archive with less than perfect documentation, on the other hand, is merely making life less easy than it might be for its staff and users -or so it seems. Hence the concentration in a new archive on building a collection, and in an established archive on the technical care of the collection and the improvement of service to users; hence, too, the repeated decision, in the face of pressure for economies, that the archive's cataloguing section is the one which may be reduced, relatively or absolutely, with least disruptive effect on the archive as a whole. Until more secure and prosperous times arrive, why catalogue?

There is more than special pleading, however, behind the argument of cataloguers that the perspective and priorities just outlined are wrong. The task of cataloguing, or rather of documentation generally, should be seen as central to all aspects of archive administration. An acquisitions policy can be effectively pursued only if the decision makers know the material already in the archive and the gaps in the collection. The work of technical care and preservation of the collection depends on adequate record keeping which, if not actually part of the cataloguing procedure, has several points of contact with it -at the simplest level, archival effort may be wasted in the unknowing care of separately acquired duplicate copies of the same recording. An adequate service to the public cannot be achieved or maintained without the provision of catalogues and indexes of high quality - the personal knowledge of archive staff is no substitute, as any archive which has lost such a human encyclopaedia to accident, illness or a new job can testify. A poorly documented archive is thus at risk in all its activities, and an inadequate cataloguing effort can only increase the level of risk.

2. The documentation needs of sound archives

The precise nature of the documentation required by an archive will depend on the type of material it collects; the requirement will also be perceived differently by the archive's staff and its outside users. In general terms, however, documentation may be considered under three headings - registration, cataloguing and indexing.

Registration

An up-to-date register or inventory of its collection is an essential administrative tool for an archive and the maintenance of such a register is therefore a high priority task, although it need not be a complex one. The process of registering an acquisition formally acknowledges - most tangibly by allotting the new item an accession number which gives it an identity within the archive - both that the collection has been augmented by a new item, and that the item is now part of the collection. The register thus provides a reflection of the archive's growth, and a starting point for all the other documentation which is likely to build up around the item.

The essential feature of an accessions register is its simplicity. Complexity invites delay or confusion, and in either of these cases the register fails to fulfill its purpose. Registers are commonly held in book form, the pages divided so that entries appear in columns under such headings as 'accession number', 'date received', 'source' (i.e. from whom received), 'method of acquisition' and 'identification' (i.e. title or description of item). Entries are obviously in accession number order. Some archives use the numbers themselves to convey information, for example by maintaining separate number runs, or reserving blocks of numbers for different types of material, or by recording each year's accessions in a new numerical run. Such practices are of dubious value they may break down (a sub-collection might grow beyond the block of numbers reserved for it) and in any case the information implied is generally available elsewhere in the documentation. A single, simple numerical sequence is on the whole the preferred approach to accessions numbering -among other benefits, it conveys a direct impression of the growth of the collection.

Individual archives will naturally vary the column headings used to register their own accessions. An archive whose material derives solely from its own staff in the field, for example, would have no need for entries under method of acquisition and source, but might substitute the name or initials of the field-worker responsible and other details such as place and date of recording. Some archives use the accessions register for additional purposes perhaps as a checklist of procedures to be followed in the acquisition/archiving/cataloguing process. Such usage does, or at least should, not violate the principle that the register is a simple document, intended as an aid to archive administration.

Cataloguing

In contrast to registration, cataloguing is a complex task, whose intended beneficiaries are both the staff of the archive and the outside users of the archive's·collection. The purpose of a catalogue is to provide, in systematic form, information on the items contained in a collection in sufficient detail to enable those who have to administer that collection or who wish to use those items to do so as efficiently as possible. Efficiency, in this context, means both the minimum waste of time and the minimum unnecessary usage of the recordings in the archive.

Information normally held in the catalogue falls into several categories, although their precise nature will obviously vary with the type of material catalogued, as is shown in the case studies at the end of this chapter. In many archives, the information categorised here is not all held in a single physical catalogue - a system of parallel files may be a perfectly acceptable alternative. It remains, however, a part of 'catalogue' information.

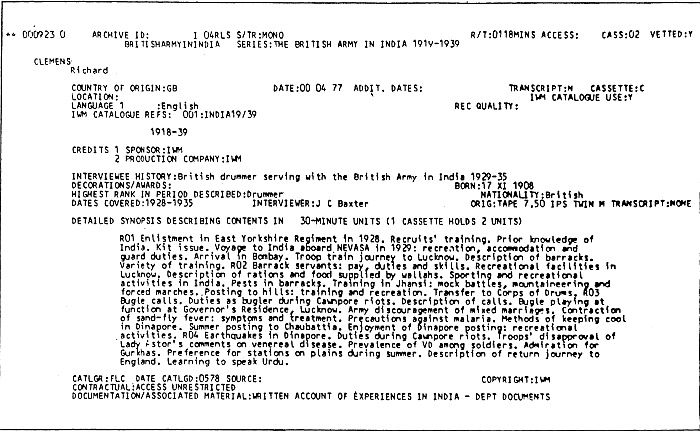

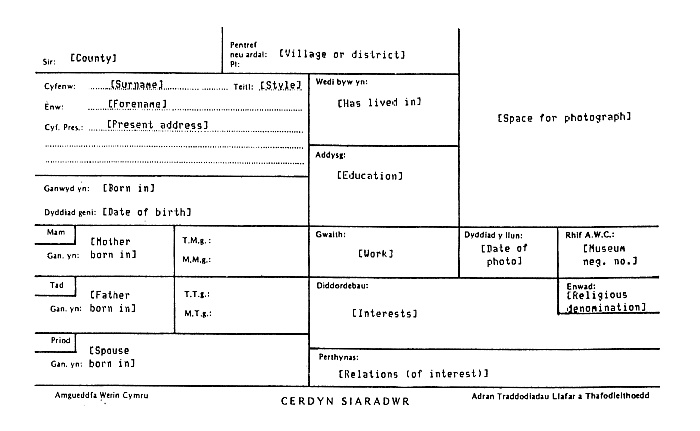

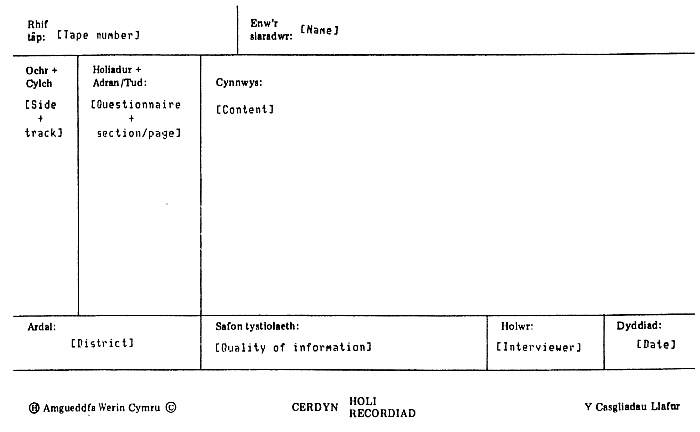

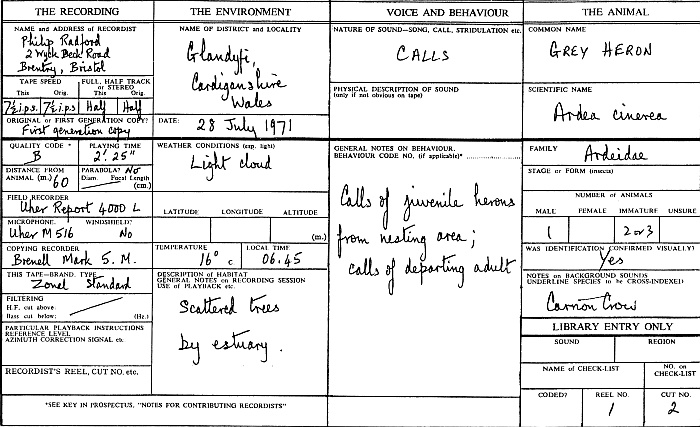

The first category is the formal identification of the recording catalogued: formal identification is identification made accurately within the rules and practices established by the archive, as distinct from the simple identification made at registration. What constitutes correct identification will vary with the material collected: an archive of commercial recordings will use the title that appears on the item catalogued, where an archive of wildlife recordings will use the correct scientific designation of the species recorded and an oral history collection the name of the person interviewed.

Since the formal primary identification of the recording may not actually be very informative, a major part of catalogue information consists of the elaboration of that identification. For collections of commercial recordings, this will generally approximate to the procedures traditional to the cataloguing of published material -the linking of title to statements of responsibility (i.e. the identification of composers or authors, performers, etc.). Collections of non-commercial recordings will have different priorities, depending on the nature of the material collected. Ethnomusicology recordings, for example, which may be identified in the first instance by the name of their collector, will require as additional information geographic (or linguistic or anthropological, or a combination of these) indications of the circumstances of the recording, including a date, and information on what was recorded. An archive collecting the proceedings of a national legislature would require information identifying the session (day and time), the topic and the speakers in a debate or committee, with, perhaps, reference to the published (transcribed) proceedings.

The purpose of providing this level of information is, first, to make unambiguous the identification of the recording (to establish, in other words, that an item is not merely a recording of Stravinsky's 'The Rite of Spring' but is the recording made by a particular orchestra and conductor on a specified occasion) and, second, to provide sufficient detail to enable an interested potential user to assess whether or not a recording contains material appropriate to his or her interests. Thus in the field of material culture a catalogue entry should make clear exactly which processes are being explained and from what perspective; in oral history, the catalogue links an interview to topics, and shows how the person interviewed relates to them. Reading the catalogue cannot be a substitute for using the collection, but a catalogue should ensure that the collection is not wastefully used and that the user's interests are matched to the material listened to as precisely as possible. This will commonly mean that users are guided not merely to specific recordings, but to specific sections of recordings. Lengthy items (especially those generated by field workers) are divided into sections -reels, timed passages, audibly-signalled segments -and the divisions reflected in the catalogue summary or synopsis.

Further categories of catalogue information include technical data on the recording, indicating the form in which it was first recorded and the form in which it would be made available to users. An archive covering more than one language will need to specify the language of recordings. The circumstances of the production of the recording would be included as subsidiary information when they do not form part of the full or elaborated identification; details of acquisition are similarly covered. This information overlaps into the question of copyright and other restrictions on access to, or use of, the material. Finally, an archive will wish to establish connections between the recording catalogued and related material such as further recordings, transcripts, related documents (photographs or text connected with the item catalogued) and bibliographic citations.

It will readily be seen that a catalogue entry providing all of the information suggested in this section will be a lengthy document in its own right. It will also be appreciated that by no means all of these details need (or indeed should) be available to all readers of the catalogue. This is best exemplified in the area of technical information. For the purposes of its own technical staff, and perhaps for professional or commercial users, an archive will need extensive details on the recording, including perhaps the machinery, tape and configuration used in the original recording. For a casual user, however, the knowledge that all recordings are made available on stereo cassette 'listening copies' might make the entire category of technical information redundant in a version of the catalogue provided for general access or sale. To take another example, the question of restriction may involve information confidential to the archive and the person concerned with the recording, when all a user need know is that there are (or are not) restrictions. These considerations underline the statement made earlier, that the product of the cataloguing process need not be a single catalogue. The provision of separate 'internal' and 'external' catalogues, or the supplementing of an open catalogue with restricted files of detailed technical or confidential information, would be acceptable, indeed logical, procedures. The essential qualification, of course, is that cross-reference between all sources of information be quick and precise. This is guaranteed by the use of a single unambiguous label to identify the recording wherever it is mentioned; the accession number is the obvious choice for such a label.

Indexing

In providing the information outlined in the previous section, an archive's cataloguers are only fulfilling a part of their function. If uncatalogued material is effectively useless (since an archive and its users may be unaware of its content in any but the most elementary sense, and may indeed be virtually unaware of its existence) then material on which information is solely available in an unindexed catalogue is only slightly more open to use. Knowledge of items relevant to particular needs will only be gained from such a catalogue by prolonged searching, by accidental discovery, or by a fortunate feat of memory by a member of the cataloguing staff. None of these constitutes a reliable basis for an archive's service.

Indexes and classification systems are provided to open up the archive by providing access points and channels to the information available in the catalogue and -by extension -in the collection itself. Additional access points are provided by sorting the information in the catalogue, or extracts from it, in alternative orders: thus a catalogue of classical music, catalogued by title, would usefully be supplemented by indexes of composers, performers and so on. Channels to information are provided by the establishment of a logical structure of indexing vocabulary and styles, so that cataloguers and researchers can be instructed to consider the collection in similar terms. For example, the same archive of classical music might wish to provide an index by chronological period. In such a case, the information would be directed into the channels by the decision either to name periods by actual year or century designations, or by epoch titles such as 'High Renaissance' and 'Baroque'. The nature of the decision taken is arguably of less importance than the fact that the decision is taken and consistently applied. It does not matter too much whether a period is called 'Nineteenth Century' or 'Victorian'; it matters a great deal if, on different occasions, it is called both (and a number of other names besides) so that a user looking up only one term will fail to find all relevant information.

The number and nature of the indexes provided by an archive will depend on many things, including the resources of the archive and the expectations of its users. The principal determining factor is the nature of the material collected. Archives of commercial recordings may concentrate on indexes of titles (which will require indexing, to restrict the potential confusion of catalogue titles in different languages or formats: 'Die Dreigroschenoper' and 'The Threepenny Opera'; 'Ninth Symphony' and 'Symphony No.9') and of authors, composers, performers, directors, etc. These concerns will be shared by collections of other types of music, such as ethnomusicology, but such collections will also share indexing requirements with other archives of field recordings -circumstances of recording, name of collector, and so on. Different types of field recording will have different priorities -place, for example, which is essential to collectors of dialect, linguistic and wildlife recordings, for example, is generally considered to be of only peripheral interest in oral history. Oral history and other essentially narrative recordings, however, require analysis by subject content -an area where vocabulary control and the structuring of an index are at the same time most important and most complex.

The style of index provided will also vary. In some archives and some circumstances, the preferred procedure is to reproduce effectively the bulk of the catalogue description for the relevant item at every entry in the index; in others, the index term is merely followed by a list of accession numbers for appropriate recordings. In some cases, attempts have been made to use extant bibliographic classification systems -such as Dewey or the Universal Decimal Classification -as a ready-made system of vocabulary control for subject indexing, while other archives use their own system of 'natural language' index terms. In a general chapter such as this one, there can be no real attempt to specify that any given solution is correct, or better than another: the choice between numeric classification codes and natural language, for example, is the choice between a system which comes ready-developed, but may prove difficult to use (because of the need to translate index statements and enquiries into number-strings), and a system whose development must be carefully planned and monitored but which may seem more accessible and 'friendly' to staff and users.

A final factor in the question of indexes to supplement or make accessible the archive's cataloguing effort is the provision of something like the indexing function through mechanisation or computerisation. At its most highly developed, technology may contradict the statements made in the first paragraph of this section: catalogue information may be held in a data-base which can be interrogated 'on line' via a computer terminal, so that physical indexes are not apparently necessary. A later section of this chapter will look at the topic of computer systems.

3. National and international standards

Most of what has so far been written has been written as if a sound archive will be established, and will be left to develop its documentation policy, in an atmosphere of almost complete freedom of choice. This will, of course, never be true. The material about which an archive is offering information will be considered by its users and others in a context which includes what is available from other institutions, and the documentation will consequently be planned under the pressures of precedent and example. Such pressures may come from several directions. A sound archive may, for example, be established within an institution which already contains a reference collection in other media -books, manuscript documents, photographs, film or museum objects and will then experience pressure to conform to procedures observed in extant collections. There may, for instance, be an institutional or national policy committed to usage of one of the MARC-derived systems. There will then be the pressure of example - the inclination to follow the methods of other sound archives which the new archive has been created to emulate or complement. There is, finally, the pressure of emergent international standards promoted by international groupings of appropriate disciplines - for example the International Standard Bibliographic Description for Non-Book Materials, or ISBD(NBM), published by the International Federation of Library Associations.

In many cases, the advantages of adhering to a standard will be obvious. Within an institution, for example, a unified cataloguing system would help ensure that users had access to all material relevant to their interests in several media -an instrument and a recording of how it sounds when played, an industrial machine and an explanation of its use, etc. Similarly, and especially in the field of commercial recordings, adherence to an international descriptive standard will help users discover the information that may be most important to them -that is, the extent to which one archive duplicates or fills the gaps in the collection of another.

There are, however, two potential dangers which should always cause an archive carefully to consider the full implications before accepting the use of a given standard. One is that the standard proposed may not, without change, be applicable to the medium of sound recordings; the second is that it may not be applicable to the specific type of material collected by the archive. The ISBD(NBM) may be used as an example: although designed as a framework for information exchange rather than as a system for archival cataloguing, the desirability of consistency in the documentation of commercial recordings inevitably makes ISBD a subject of great interest for cataloguers of sound material. In 1980, a joint working group of the Cataloguing Commission of the International Association of Music Libraries and the Cataloguing Committee of the International Association of Sound Archives submitted to IFLA detailed recommendations for the improvement of ISBD(NBM) as applied to sound recordings. Points requested by the working party included, for example, the elaboration of rules in ISBD(NBM) governing responsibility statements and physical description, and of cautionary notes concerning the application to sound recordings of the concepts of 'editions' and 'series'. These points are additional to those acknowledged in the ISBD itself: that it is primarily concerned with 'materials published in multiple copies' and excludes 'specimens or found objects' (which category may be taken to include field recordings), and that it 'may require elaboration' to meet the requirements of archives.

ISBD(NBM) is far from unique in any of these respects. Like it, most cataloguing standards derive from the world of librarianship, and many are, for example, not compatible with the sound archivist's perception of 'responsibility' (multiple, and shared between author and performers) as distinct from the more conventional concept of authorship. Outside the field of commercial recordings, the problem may well get worse. Geared to titles and responsibility, standards may not cater adequately for the preferred identifications of field recordings, and may not accommodate the desirable level of description for such works. While, therefore, adherence to standards is an admirable target for sound archive cataloguing, a new archive should be entitled critically to examine the specific applicability of any single proposed standard to its cataloguing needs, and to seek necessary improvements in the standard as an alternative to compromising its own practices.

4. Computer systems

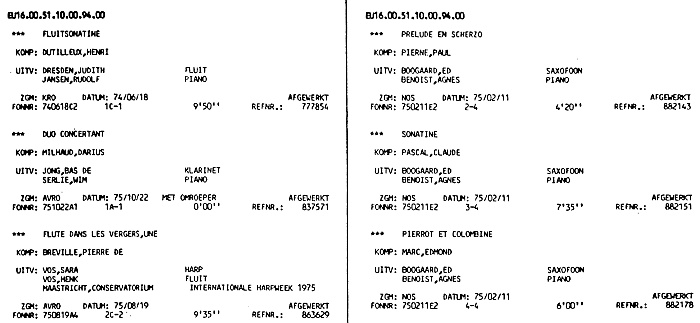

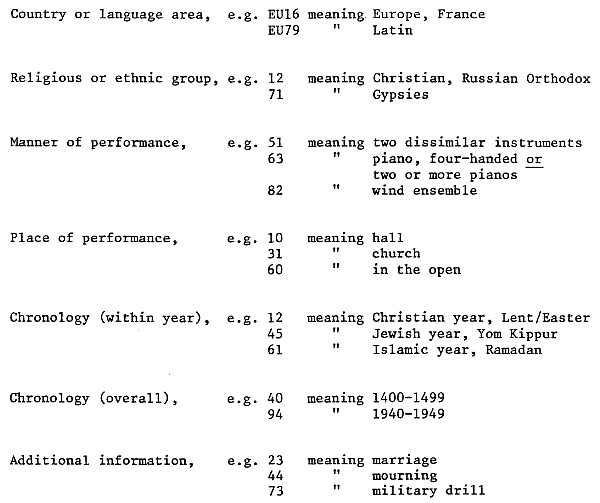

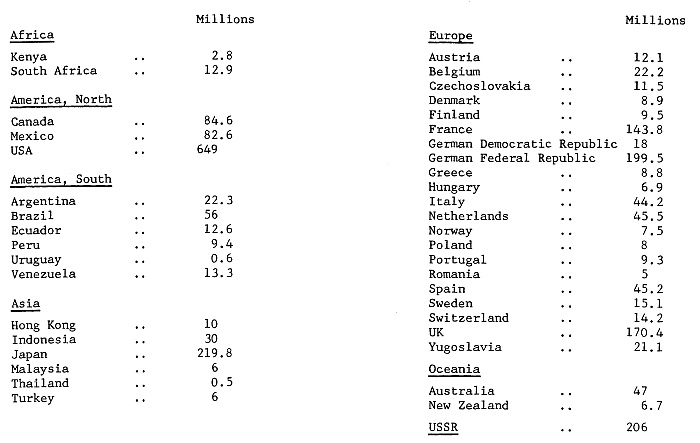

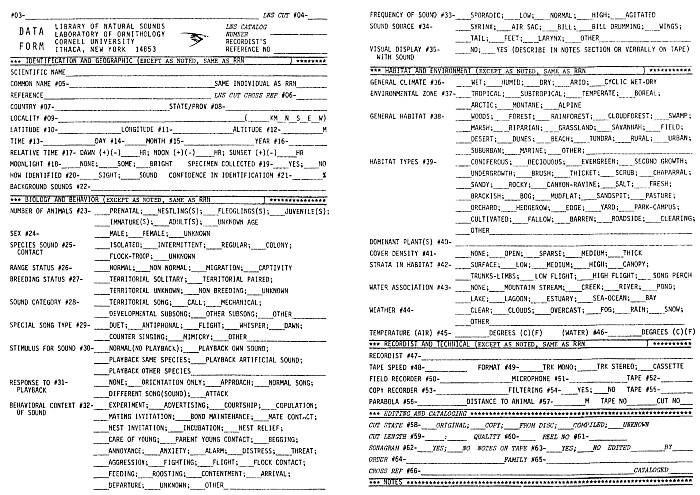

A further dimension to the questions discussed in the previous section, and a topic of increasing general relevance in any case, is the possibility of the involvement of mechanisation or computerisation in cataloguing. Computers are becoming more accessible year by year: the equipment itself is becoming cheaper, and there is an increasing choice of program packages for computer applications, including cataloguing. The only dimension lacking, perhaps, is a realistic appraisal of what computer usage mayor may not really involve.