6. Commercial Records (Pekka Gronow)

1. Introduction

At least two billion records and pre-recorded cassettes are sold annually in the world. In the most industrialized parts of the world almost every home has a record or cassette player and miniature 'sound archives'. Even in less developed countries, commercial recordings have a long history and enjoy considerable popularity. There are very few countries without regular commercial production of sound recordings. 1

To the sound archivist, commercial recordings are just one type of sound recording. The archivist who is specially concerned with, say, wildlife recordings, political speeches or folk songs, does not attach much importance to the question of whether a particular recording derives from a broadcast, a commercial issue or a recording specifically made for his archive. From his viewpoint, this is a perfectly valid approach. Commercial recordings have a variety of content and may be of interest to any type of sound archive.

However, there is another way of looking at the matter. This is perhaps best illustrated by the analogy with written material. There are many different types of written documents, ranging from manuscripts and official documents to newspapers and books, and there are also many kinds of libraries and archives that preserve written materials. But many countries have a national library which has the task of preserving the most important printed works published in the country. In several countries the national library actually has the task of preserving a copy of every book and periodical published. The printed word has a wide audience; it has left some mark on national culture and thus deserves to be preserved for future generations.

It makes sense to look at commercially issued sound records in the same way as printed books are viewed. Such recordings have also been made public; they have become permanent statements and deserve to be preserved. The number of recordings issued in any country is certainly much smaller than the number of printed works. If a country wants to preserve a complete or representative collection of its published literature, it should also pay similar attention to published sound recordings (not forgetting films and other moving images).

- 'Commercial' in this connection simply means that the recordings are offered for sale to the public. It does not necessarily imply the existence of a profit motive or a specific economic system. 'Non-commercial' recordings are those made exclusively for broadcasting organisations, archives or private use and which may not generally be available for purchase.

2. A national collection of commercial recordings

This chapter is based on the assumption that every country should preserve a complete or representative collection of its national record production for posterity; an audio counterpart of the national library. However, much of the advice given here is equally applicable to other situations, such as specialized sound archives wishing to build up a collection of commercial recordings related to their field of study.

The idea of a national collection of commercial recordings was first introduced in France, where the Phonothèque Nationale was founded in the 1930s. It has become part of the national library, the Bibliothèque Nationale. In the United Kingdom, the British Institute of Recorded Sound collects not only commercial recordings but also wildlife sounds, documentary recordings, folk music and broadcasts. In Sweden, the Arkivet för Ljud och Bild is the central archive for commercial recordings, radio and television broadcasts, and films. In Denmark, the Nationa1diskoteket is part of the National Museum. In the United States, the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress was established in 1978, combining a number of previously existing archives into one unit. There are also several other important American collections of commercial recordings which specialize in particular types of music, such as the John Edwards Memorial Foundation at the University of California, Los Angeles (country music), the Rodgers and Hammerstein archives at the New York Public Library (popular music) and the Yale University collection of historical recordings (opera).

The above examples show that it is not possible to say how the national record collection should be organized. It can be an independent body or part of a larger institution. There are obviously several alternative models. The important thing is that some institution or institutions should bear the responsibility for this task, the scale of which may be judged from the history of the record industry.

3. A brief history of the record industry

After the invention of sound recording in 1877, recordings were made individually on wax cylinders for almost two decades. Very few recordings from this period survive.

In the 1890s, it became possible to duplicate cylinders and discs on a large scale and, after the turn of the century, the commercial production of sound recordings really got under way. Half a dozen US, British, German and French companies soon assumed leading positions. These companies operated on a global scale. They established subsidiaries and agencies in as many countries as possible and sent their recording experts to record local music in order to promote more interest in the new invention. During the decade preceding the First World War, records enjoyed an astonishing popularity and cheap spring-operated record players found their way even to remote villages where electricity was still unknown. Between 1898 and 1921 a single company, the Gramophone Co. (UK), is known to have made a total of 200,000 different recordings. The Company made recordings in most European, Asian and North African countries.

The First World War naturally reduced sales, but in the 1920s records again became popular. In addition to the established international companies, there were now a number of smaller local companies. As recording technology was still relatively expensive, however, many small countries still lacked a local industry. For instance, there was no local record industry in Finland, Denmark, Norway or Ireland until the late 1930s, and all recordings made in these countries were produced and pressed by foreign companies.

The worldwide economic depression of the early 1930s and the simultaneous introduction of sound film and radio broadcasting made record sales drop to one tenth of the previous decade's level. Many record companies went bankrupt and information about their activities was lost. In the late 1930s sales increased again, but another world war intervened and not until the 1950s did record sales again reach the peak level of 1929.

In the 1950s, the introduction of microgroove (long playing and single) records and the general improvement in the standard of living increased the demand for records, and for the past three decades world sales have generally been moving upward. With the introduction of magnetic tape, recording became much easier and the number of small independent record companies increased dramatically. A local record industry has now been established even in areas where relatively few recordings were made before the war, such as Africa south of the Sahara, the Pacific and small Caribbean countries.

Pre-recorded cassettes and cartridges and cheap cassette players were introduced in the late 1960s. Cassettes soon became very popular and, especially in Asia and the Arab countries, sound recordings now reached a much wider audience than ever before. The duplication of cassettes is so simple that it has also created the new problem of record 'piracy' - the unauthorized duplication of recordings -which has become a large underground industry especially in countries where copyright legislation has lagged behind technological development.

Today there are literally thousands of record companies in the world, but the structure of the international record industry still reflects historical development summarized above. About half of all records produced in the world are made by a dozen huge international corporations, many of which are direct successors of the industry's pioneers. For instance EMI, the world's second largest record company, is descended from the Gramophone Company that was founded in 1898. These international corporations have subsidiaries or agents in most large countries. They produce many different types of recordings, both internationally known classical and popular music and national idioms. (Melodiya is an exception among the largest companies since it operates solely in the Soviet Union. As the only record company in one of the world's largest countries, however, its record production easily surpasses that of many multi-nationals.)

The scale of activities by the largest ten of those companies may be illustrated by their sales figures in 1977.

| US$ | |

|---|---|

| CBS (USA) | 770 million |

| EMI (UK) | 750 " |

| Polygram (Federal Republic of Germany/ Netherlands) |

750 " |

| Melodiya (USSR) | 580 " |

| Warner Communications (USA) | 530 " |

| RCA (USA) | 400 " |

| MCA (USA) | 100 " |

| Transamerica Corp. (United Artists) (USA) |

90 " |

| Bertelsmann (ariola-Eurodisc) (Federal Republic of Germany) |

90 " |

| A & M (USA) | 80 " |

This table is based on material compiled by Martti Soramaki and Jukka Haarma.

The thousands of smaller companies usually operate only in one country or region. They often specialize in regional music, in special categories of music or in other specific types of sound recordings. Of course, such companies may vary considerably in size, from enterprises employing, say, a hundred people to being one man's part-time occupation. All are nonetheless small when compared with the world's largest record companies. There are companies specializing in Eskimo music, the songs of one religious sect, reissues of early operatic recordings, sound effects and documentary recordings of the Second World War. The sales of such recordings may be relatively low -often only a few thousand copies and a mere trifle when compared with international hits selling several million -but the combined number of different recordings issued by the small companies is tremendous and their total sales are by no means unimportant.

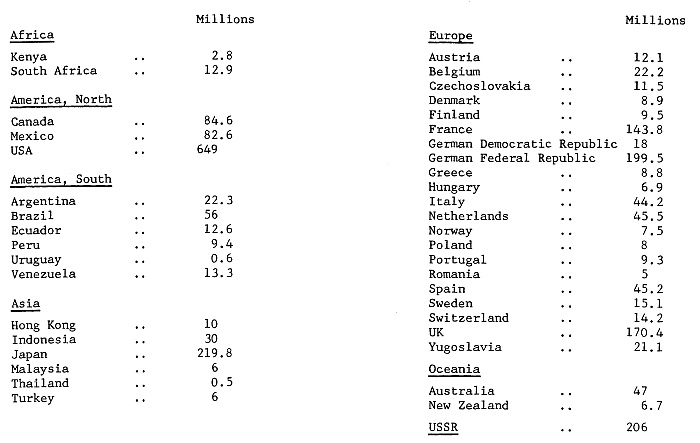

As an indication of the record industry's output the table set out in Figure 1 may be useful. The figures on the sales of records and pre-recorded cassettes are intended as a preliminary guide. International statistical publications such as the UNESCO Statistical Yearbook do not yet include sound recordings, and the accuracy of these statistics is in some cases questionable. Most of the figures shown are from 1979 or 1980, and were obtained from the International Federation of the Producers of Phonograms and Videograms and from Billboard magazine.

Figure 1

4. How to start a collection

The definition of national record production

We have touched on the necessity of preserving examples of 'national record production' without defining this term. It is not as simple as it may seem.

Throughout the history of the industry, records have frequently been manufactured outside the country where the original recordings were made. A German record company makes recordings of a Danish artist in Finland, has them manufactured in Sweden and sends them back to Finland for sale. Are the records Finnish, Danish, Swedish, or German? It depends on the viewpoint and it is impossible to give a universally acceptable answer. Countries with a strong record industry may produce records that are intended for export only. Very small countries may have no local record industry and even recordings of their national music are made by foreign companies abroad. Sound archives may, with good reason, adopt quite different definitions of national record production.

To give an example, Suomen äänitearkisto (the Finnish Institute of Recorded Sound) considers every record manufactured in Finland to be national production. Most such records are, it is true, recorded in Finland by Finnish artists, but there are exceptions. In addition, all records published by Finnish companies are considered to be national production even if they are manufactured abroad. In this case, too, the records usually have a clearly Finnish character. In addition, the archive collects recordings made in the Finnish language (often by Finnish immigrants) in the USA, Canada, Sweden and the USSR, although they are not formally considered national production. This definition is practical in a relatively small country with a locally oriented record industry, but other countries will have to formulate their own definitions. The country of manufacture, the domicile of the record company, the recording site, the nationality of the performer, and even the language or style of the performance may all be involved in the definition of national production.

Complete or representative collections?

Should every record or only a representative selection of recordings be preserved?

The majority of commercial recordings feature popular music of various types. It may be argued that not all recordings are worth preserving. Certainly many popular recordings may be of ephemeral interest only. But it is very difficult to know what will be considered valuable fifty years from now. Folk music was once despised by many people; now it is studied seriously everywhere. Urban popular music was in turn considered by scholars to be inferior to folk music, but 1981 saw the founding of an international association devoted to the study of popular music. Many popular records made in the 1960s have already become eagerly sought collectors' items.

Very few countries publish more than a thousand LP records annually. It takes about three metres of shelf space to store a thousand records. In many countries the complete record production of many decades can be stored in one small room. In most cases there cannot be any real practical objections to preserving a copy (or better still, two copies) of every nationally produced record. In my opinion, it is far better to waste a little space on unimportant recordings than to risk the complete disappearance of some important ones.

If every country were to assume the responsibility for preserving copies of its national record production not an unrealistic or unreasonably expensive task -we could be certain that an important part of human creativity was being preserved for posterity. Later it will be much more difficult and often impossible to fill in the gaps.

New domestic production

The simplest task of archives is to obtain new domestic production. The obvious way to get started is to buy copies of new recordings as they are issued, either from retail stores or directly from record companies. In most countries the annual cost of purchasing one or two copies of every new domestic recording issued is quite reasonable.

The main objection to this method is not its cost but the problem of obtaining a truly complete collection. In countries where there are many small record companies, or where some records for national consumption are manufactured abroad, it may be difficult to keep track of new releases. By the time the archives learn about the existence of a new recording it may already be sold out.

It is therefore better to establish direct contact with all record companies in your country. IFPI, the International Federation of Producers of Phonograms and Videograms, has recommended that its members donate sample copies of their production to national sound archives. This system of voluntary deposit has worked successfully in several countries. Of course the receiving institutions must be clearly designated and have national status. Record companies cannot be expected to distribute free copies to all and sundry.

However, this system has many of the drawbacks of purchasing records. In many countries there are small companies that are not members of national record industry organizations. It may be difficult, therefore, to establish contact with all record producers. For this reason many countries have introduced the system of the legal deposit of sound recordings.

The legal deposit of printed works has a history going back several centuries. In numerous countries printers and/or publishers are required to deposit copies of their publications in one or more libraries. In Finland, for instance, printers are required to deposit five copies of all books and periodicals printed; the copies go to the Helsinki University Library and four other University libraries in other parts of the country. Several countries have already extended legal deposit to include sound recordings. Such countries now number about 30, although it seems that in some cases the legal deposit of sound recordings is based on the registration of copyright and the recordings received are not always properly cared for.

The details of such legislation naturally vary from country to country. In some countries the legal deposit of sound recordings includes both domestic production and imports (records imported in some quantity for sale). In countries where legal deposit is connected with copyright, it usually involves only new production and not reissues. In Finland, record manufacturers (both record pressing and tape duplication companies) are legally required to deposit two copies of every record and cassette manufactured. In addition, record companies are obliged to deposit copies of Finnish recordings they have manufactured abroad. Foreign recordings are not included unless they are actually manufactured in Finland.

The legal deposit of sound recordings is, in most cases, the ideal method of building up a national collection of commercial recordings. The absence of such legislation need not, however, deter any country from starting a national record collection. Some of the finest record archives in the world have acquired their collections through voluntary deposit, purchase or a combination of the two.

Historical recordings

The first commercial recordings were issued in the 1890s. A tremendous number of recordings had, therefore, already been made before the first national sound archives were established and in many cases these recordings were lost without a trace. Consequently, any serious sound archive is soon faced with the problem of obtaining out-of-print commercial recordings. Some may be only a few years old, some four-score, but the problem remains the same.

Why not go to the record company which originally produced the record? In the case of recent recordings this is often a good idea, and the company may be persuaded to find a duplicate or make a tape copy. But my experience is that most record companies do not have proper archives, and when a record is no longer commercially viable, even archival copies are destroyed. Even where record companies do have archives, they are seldom properly cared for (material borrowed by staff is not returned, etc.).

The introduction of microgroove records in the 1950s seems to have been a turning point for many companies. When the 78 rpm speed was abandoned, existing stocks of older records (including archival copies) were often destroyed. As far as I know there are only three record companies in the world with large archives dating back to the early years of the industry. (There may be others, and an important task for research is the inventory of the archives of leading record companies.) These companies are EMI Records at Hayes, Middlesex, outside London, and CBS and RCA, both in New York. EMI is the successor of the Gramophone Company, founded in 1898. The EMI archives are unusually well organized and include archival copies of most records made by the Gramophone Company (but not by other EMI subsidiaries). This means that the archive contains recordings made since the turn of the century in most countries in Europe, Asia and North Africa.

The RCA (formerly Victor) and CBS (formerly Columbia) archives are not as extensive as those of EMI. In many cases the records themselves have not been preserved, but only the metal masters which were used to stamp records (and can still be used to make test pressings). Columbia and Victor had business connections in many European and South American countries and the archives also contain material from these countries.

The EMI, RCA and CBS archives are not open to the public. They are inadequately catalogued and it is often very difficult to find out whether particular items have actually been preserved or not. All three companies have occasionally cooperated with sound archives and made copies of their holdings available. All three archives also contain a large number of recordings which have probably not been preserved in any way in their country of origin. It is to be hoped that in future some way could be found of making these archives more widely accessible. This would mean some kind of agreement which takes into account both the legitimate economic interests of the companies and the interests of sound archives and historical research.

When searching for historical recordings it is, of course, also advisable to contact other established archives, whether national, specialized or broadcasting. Over the years many archives have accumulated foreign material and in my search for old Finnish records I found many important items in Sweden. The British Institute of Recorded Sound is an example of archives which have material from many countries. Many archives are willing to copy material for other archives, especially if an exchange is involved, but it must be remembered that copyright may in many cases restrict copying unless the permission of the copyright owners can be obtained (see section 11 on copyright).

Sooner or later the archivist is also likely to come into contact with private record collectors and dealers. Before the establishment of public sound archives many private individuals were already collecting old records as a hobby. Ali Jihad Racy, a specialist in Arab music, was able to write an important article on the history of Arab music by relying on private record collectors in Egypt and Lebanon. 1 His material was obviously not available in any public archive.

Private collectors can be of considerable value to sound archives. They can often spend much more time searching flea markets, antique shops and other sources for old records than can the professional sound archivist and they are usually willing to sell, exchange or lend their material.

But how much are old records worth? So far there is no market for old records comparable to the market for old books, stamps and certain antiquities. In some specialized fields, such as operatic singing and jazz, there is an established network of mail auctions, dealers and specialist shops and in such fields it is also possible to speak of established prices. But in general the prices of old records are much lower than the prices of old books of comparable rarity. I have purchased hundreds of interesting historical recordings dating from 1900 to 1950 for prices ranging from $0.50 to $5 (US). Even well-known collectors' items can often be bought for prices ranging from $10 to S25. There are records that might sell for a hundred dollars or more, but they are few in number and specialists in these fields could easily list them. 2 I am mentioning these figures because the absence of established prices sometimes makes the uninitiated think that any old record must be tremendously valuable just because it is old. A record by a famous singer like Caruso must surely be worth a lot! In fact Caruso's records sold so well in their time that they are still quite common and, with a few rare exceptions, can be purchased from specialists at very reasonable prices.

The absence of an international collectors' market has tended to keep prices down, but it also makes finding some records very difficult. If I am looking for original US jazz records from the 1920s or German opera singers of the 1930s, I know dozens of people through whom my needs may be met. But if I am interested in finding African recordings made before the Second World War or other items which are not generally collected, I can only hopefully pass the word around to fellow collectors, ask archives in various countries or hope for a lucky find in the flea markets of some large city with an African population. The situation being as it is, I would advise all sound archivists to establish good relations with private collectors.

- Racy, A.J. 'Record industry and Egyptian traditional music, 1904-1932' in Ethnomusicology Vol.20, No.1; 1976

- 1915-1965 American Premium Record Guide published by L.R. Docks (P.O.Box 13685, San Antonio, Texas 78213) gives estimated prices of several thousand US jazz, blues, country and popular records. The prices range from $3.00 to $100.00 or more with the majority being under $10.00. Please note, however, that there are thousands of records in these categories which are not listed in the book because their value would be less than $3.00.

5. A case study: Finland

I hope I will be excused for using my home country as an example, but I feel that many of the problems we faced in establishing an archive of commercial recordings in Finland are quite typical.

In the early 1960s, the Finnish Broadcasting Company had the only large collection of Finnish recordings. Even this collection did not go much farther back than the 1930s, was quite incomplete and was not open to people outside the company. Nobody seemed to know, or to care very much, what Finnish records had been issued at the beginning of the century.

In 1965 a group of private collectors, scholars, and record industry people got together and decided to found a sound archive. All Finnish record companies agreed to donate sample copies of their future production and, moreover, copies of their earlier recordings which were still in stock (most of them from the 1960s). Some storage space was obtained without rent and at first all work was done by volunteers. Later some financial support was received from the Ministry of Education.

The task then remained of acquiring older recordings. As nobody really knew what records had been issued, it was decided to embark on two simultaneous projects: to collect as many older Finnish records as possible and to compile a complete list of Finnish records, regardless of whether they could be found or not. For this purpose, private and broadcasting archives, old record catalogues preserved at the Helsinki University Library (thanks to the legal deposit of printed works!), the files of record companies and even advertisements in old newspapers were consulted. Archives in Sweden, Denmark, the UK and the USA were visited, and it was discovered that they had few Finnish recordings but a great many valuable record company catalogues in which Finnish records were listed.

Copies of old records were gradually acquired through purchase or donations. The acquisition of a large collection of Finnish-American records from a former producer of Finnish language radio programmes in the USA was especially lucky. But recordings made before the First World War remained particularly hard to find.

At this point it was learned that the EMI archive at Hayes in England had a large collection of early Finnish records. The archive had no index but as we had already compiled lists of the records, based on old catalogues, we were able to provide catalogue numbers and titles of the records required. EMI then agreed to make tape copies for a reasonable price. In about fifteen years, with the help of many private collectors and other archives, the Finnish Institute of Recorded Sound has been able to acquire a fairly large collection of Finnish records, including many which were completely unknown at the time the archive was started. This work has not been only of historical and academic interest. It has also provided material for numerous radio programmes, new recordings of old songs by contemporary artists and dozens of reissue LPs of historical recordings (in many cases by record companies which had forgotten that they had once made such recordings and lost their material!).

6. Foreign recordings

The first task of every country is to preserve its domestic record production, but this alone is not enough. There should also be examples of important foreign recordings, for students of history, music and languages, for historians of sound recording and for the general public. During the history of commercial recording, a few million different recordings have been issued all over the world. What should be chosen for archival preservation?

In a country with a large market for imported records, one answer is obvious. Obtain representative examples of recordings sold in your country. They have obviously influenced cultural life there and there has clearly been some demand for them. In fact, some countries have extended legal deposit to include imported recordings.

This still is hardly sufficient. Only a fraction of all recordings issued are distributed outside their country of origin. The sound archives that want to build up systematically a collection of international recordings must also keep an eye on what is published in other countries.

Of course it is impossible to give universally acceptable guidelines for the planning of such a collection. Who is going to use the collection and for what purpose? Is it for students of music, folklorists, ethnomusicologists, historians or political scientists? Is the intention to build up a collection covering the history of Western art music, the main musical traditions of the world, the history of recorded sound or examples of the voices of famous historical and political figures? There are numerous possibilities. The choice should also take into account what other archives in the country, and perhaps also in neighbouring countries, are doing. Archives in Central Europe will probably have different goals from those, say, in South East Asia or in the Caribbean.

In any case, a sound archivist will probably soon find that he cannot rely too much on retail stores and importers in his own country, because they are not likely to be interested in obtaining one or two copies of some obscure recording. He-may, therefore, have to find suppliers abroad. If there are currency restrictions the best solution would probably be to establish exchange programmes with suitable foreign archives. This procedure is quite common among libraries. Even if there are no problems in obtaining foreign currency, finding the right suppliers may be quite complicated.

In some cases, the archivist should probably write direct to the record company. My experience is that many small record companies are quite happy to handle small postal orders. Large companies often sell wholesale only, however, or may be contractually prevented from selling direct to buyers in other countries (even if the appointed agent in their area does not stock the items required or refuses to accept small orders!).

Often the best solution is to find a reliable retailer who is willing to handle postal orders and go to some trouble to find unusual records. The prospects of finding a good supplier depend on the country, the types of recordings concerned and, obviously, also on the amount of money you are going to spend. A good way to get started is usually to look for advertisements in music or record trade periodicals and then place a small sample order.

Even then the archivist must know exactly what he is looking for. This involves finding out from periodicals, catalogues, and discographies (see section 7) what records are available and what their catalogue numbers are. It should be remembered that the same recording is often issued under different catalogue numbers in America and in Europe (often, even in different European countries, the numbers vary). Do not try to order out-of-print recordings from dealers who only sell current recordings. The previous section on historical recordings gives some hints on sources for out-of-print recordings.

7. Catalogues and discographies

Many countries regularly publish national bibliographies, catalogues of books and periodicals published in the country and acquired by the national library. There are also innumerable bibliographies on books and articles on various subjects. Discography, the systematic cataloguing of records, is a much less developed branch of library science. Only very few countries have made attempts to produce national discographies and, in most cases, these are only partial attempts, listing only recent or only historical recordings. Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, and the Federal Republic of Germany should be mentioned in this connection.

Recently there has, however, been increasing interest in discography. Specialists have published discographies of various types of recordings, such as operatic singing, violin playing, jazz, film music, dance orchestras, certain composers, speeches, etc. Most of these publications are mainly concerned with records issued in the English-speaking countries, while in other parts of the world there has been less interest in discography. There have also been discographies listing all recordings (or certain categories of recordings) published by a single record company and this is already a step towards a national discography. Certain types of music, such as jazz, are already quite well covered by discographies, but others are hardly touched at all.

In this situation the second best source of information is usually commercial catalogues published by and for the record trade. Most record companies regularly publish catalogues and newsletters listing new releases and other recordings currently available. In some countries there are also collective catalogues listing all (or most) recordings currently available for the trade. Well known examples are the Schwann catalogue in the USA, Music Master and Gramophone in the UK and Bielefelder in the Federal Republic of Germany. Such catalogues are invaluable for two reasons. They list records currently available and show their publishers and catalogue numbers. But even later, when the catalogues are no longer current, they are useful check lists of recordings that have been published, many of which are probably not listed in any other source. In fact sound archives would do well to obtain as complete a collection as possible of catalogues issued by record companies in their country, and at least occasional copies of the main international catalogues mentioned above. Afterwards such catalogues will be almost impossible to find. Record company catalogues published at the beginning of the century are already collectors' items which in many cases cost more than the records they list.

8. Technical considerations

The operations of archives of commercial recordings do not differ much from those of other sound archives. You need storage space, staff, a cataloguing and filing system and technical equipment. But while other sound archives will mainly be using open-reel tape, commercial recordings are mainly issued on records (discs) and cassettes.

Modern microgroove records (LPs and singles) are not likely to present any special problems. They are quite durable (if direct wear, scratches and other physical damage are avoided) and can be safely played even on moderately priced record players if the stylus is checked frequently and changed before it is worn. Information on record players and other high fidelity equipment is readily available from dealers, manufacturers and specialized publications.

Pre-recorded cassettes and cartridges do not, in principle, differ from open-reel magnetic tape and the instructions given elsewhere in this book should apply for cassettes as well. However, in practice, pre-recorded cassettes are usually of much lower quality. Their quality varies tremendously, and they also frequently have mechanical faults which cause problems. Cassettes are such a recent invention that there is not yet much information on their preservation. Any archives which hold cassettes in their collections should -especially if the identical material is not available on disc -pay special attention to them and check their condition regularly. It would probably be safest to copy the most important recordings immediately onto high-quality open reel tape.

The older type 78 rpm records were standard in the record industry until the 1950s and in some countries they were manufactured even later. Today they are hardly made anywhere. From an archival viewpoint the old '78' was an excellent sound carrier if direct mechanical damage was avoided. Most of the shellac compounds used for the manufacture of records seem to be quite stable and 78 rpm discs seem to withstand the ravages of time better than paper, film or magnetic tape. Very little can happen to properly shelved shellac records, although at high humidity certain types of mildew growing on paper sleeves can damage shellac. Even dirty old records which have not been properly stored can frequently be improved by washing them carefully with water (preferably distilled) and a liquid detergent.

The main problem is playing the records. Old records should no longer be played on old record players with steel needles and heavy pick-ups, unless a specialist is available who can ascertain that no damage is caused to the record. Fortunately, modern light-weight pick-ups (except some of the more expensive types) can usually be adapted for 78s. At least one company, Shure, commercially manufactures styli for 78s and there are specialist companies, such as Expert Pickups in the UK, which will supply diamond styli for 78s. Several different types are available, corresponding to different makes and periods of 78s. Many archives have had excellent results with these styli.

Speed control can also cause great problems. Few record players any longer have the 78 rpm speed, although there are still some relatively expensive models with 78, 45 and 33 rpm. If one of these cannot be located it may be possible to have some other model modified so that the 45 rpm speed is changed to 78. Early records were seldom made to play at exactly 78 rpm. Before 1920 the correct speed could just as well be 74 or 80 rpm, so archives may need access to record players with variable speed controls. There is no way of knowing exactly the correct speed, but if an early recording sounds unnatural at 78 rpm then correction should be attempted by trying to vary the speed. Jeffrey Duboff, a specialist who lives in Massachusetts, supplies a variation of the Sony record player which has adjustable speed from 65 to 105 rpm, in addition to the standard 45 and 33. Speeds as high as 100 rpm may be necessary in special cases.

Before the lateral-cut 78 rpm shellac disc became standard in the record industry, it had several serious competitors. The situation in the record industry at the beginning of the century resembled today's video market with several competing systems. There were even oddities such as the 'World' record, which had to be played at a constantly changing speed. Few archivists are likely to encounter the most unusual types and the problems of reproducing them are so specialized that we need not discuss them here. If you meet very special types of recordings ask other, older archives for advice. I shall, however, discuss briefly the most common 'non-standard' recordings.

Cylinders were manufactured commercially from the l890s to the 1920s and, even later, blank wax cylinders were used on dictating machines. Cylinders were made from many different materials, came in different sizes and were played at different speeds. The reproduction of cylinders is a highly specialized field and there is even one specialist company which supplies modern electrical cylinder players which accommodate most types of cylinders. Basically. it is not too difficult to build a moderately successful cylinder player which uses a modern stereo pick-up and several articles on this question have appeared in specialized publications.

Vertical cut discs sometimes look like ordinary 78 rpm discs, but when played on a normal record player little sound is heard. However, with a suitable stylus, a stereo pick-up, the correct speed and using only one channel of the stereo signal, they can be reproduced quite satisfactorily. The main makes were Pathe and Edison. Edison discs are usually 10-inch, the same as most 78s but much thicker, and they play at 80 rpm. Pathe discs come in many sizes up to 14 inches, sometimes play from the inside out and were usually recorded at approximately 80 or 90 rpm. There were also other early manufacturers so, if you encounter early recordings which reproduce poorly make sure that they are not vertically cut.

The sound of old recordings, both standard 78s and more unusual makes, can usually be considerably improved by using filters, equalizers and other more specialized electronic equipment. Such miracles of modern electronics are useless, however, unless the proper stylus and correct speed are used.

9. Staff

There are few training programmes for sound archivists and hardly any for archivists specializing in commercial recordings. Such an archivist needs a combination of several skills: some knowledge of sound reproducing equipment; familiarity with the practical operation of archives and libraries, such as cataloguing, indexing, shelving; a basic knowledge of the history and structure of the record industry; some musical training, if possible.

One person need not necessarily have all these skills. The technical aspects of sound reproduction can be handled with outside help. But the successful running of the archive requires a combination of library or archival training and a basic knowledge of the record industry. Both are equally important. Many of the tasks in sound archives are no different from those in a library, but the mechanical application of library or archive training without an understanding of the peculiarities of recordings can produce disastrous results. The cataloguing rules for sound recordings developed by libraries may be good for a public library which must handle both books and recordings, but they are inadequate for sound archives with historical recordings. The best background for a sound archivist specializing in commercial recordings would probably be basic library or archive training combined with an extensive reading of literature. He should make visits to older sound archives; correspond and have personal contacts with other archivists, collectors and record industry people; and have a genuine interest in recordings.

How many staff are needed? This depends on the size and collection of the archive, the input of new recordings, the complexity of the cataloguing system, the services offered to the public and other factors. It is relatively easy to estimate the working time required for the cataloguing of a certain number of recordings annually and the operation of a listening service (and reading room for printed material on sound recordings). It is more difficult to estimate how much time is needed for contacts with record producers (there are always problems with getting recordings), correspondence with other archives and scholars, the search for historical recordings and administrative work. Archives will have to estimate for themselves how many staff the ideal operation of their archive would require, and then comfort themselves with the knowledge that most archives have to do with less! It is also important to remember that the first task of archives is to preserve material for posterity. Even if it is not possible immediately to arrange the proper cataloguing of recordings, a listening service and so on, it is important to acquire recordings so that they are not lost.

10. Security

Most sound archives have been established by a few dedicated individuals who have personally supervised everything. Access has probably been limited to a small number of equally dedicated specialists. Then the archives grow. More staff are employed, often on a temporary basis. The number of users grows considerably and one day it is discovered that valuable recordings have been lost.

All archives must pay attention to the security of their collections and archives of commercial recordings are likely to have larger problems than, say, archives specializing in wildlife sounds. The typical 'thief' who takes material from archives is not a professional criminal but an enthusiastic visitor or a staff member who thinks that he needs a particular item more than the archive and that the loss will not be noticed anyway.

The best precaution against the loss of material is the establishment of simple rules for the removal and return of material from shelves, for taking material off the premises, for locking and opening doors and having access to keys, for the inspection of bags and so on. The existence and observance of such rules will probably eliminate most security problems.

11. A note on copyright

All sound archives - especially those concerned with commercial recordings - will sooner or later come into contact with copyright legislation. Can we make tape copies of records for researchers or for exchange with other archives? Can we make duplicates for our internal use? Can we charge for copies?

The details of copyright legislation vary considerably from country to country and the copyright of sound recordings is not always as clearly established as, say, the copyright of printed works. The following should consequently be read only as a general outline of the subject; individual archivists must thoroughly understand the law in their own countries. However, some general principles are common to the copyright legislation in most countries.

A commercially published sound recording usually utilizes two separate types of copyright:

the rights of the author(s) of the recorded work (composer, lyricist, arranger, etc.). These rights are often controlled by a publisher and/or a copyright organization;

the rights of the performer and the record company, usually controlled by the latter and/or a performing rights organization.

The author or owner of a copyrighted work has the exclusive control of the use of the work. Thus archives making a tape copy of a recording for their internal use may be breaking a law, unless this is specifically permitted in the country's copyright law or the archives have the permission of the copyright owners.

Laws must be obeyed, but copyright must never be an excuse of inaction. There are least three different ways of ascertaining that archives can make necessary copies and in other ways utilize copyrighted works.

(a) Obtain Necessary Permits

Especially in countries where composers and record companies have representative organizations, it might be relatively easy to obtain permission to make copies of copyrighted recordings for archival use or exchange. A payment may be demanded but this need not be excessively high. The copyright owners may also realize the importance of archives and grant certain rights free of charge. Even if a general arrangement is not possible permission may be sought in specific cases, for instance when an exchange with a foreign archive is involved. Never use copyright problems as an excuse for refusing to make copies unless you have at least asked the copyright owners.

(b) Exceptions Provided by Law

In most countries, copyright legislation provides some exceptions to the general principle. In some cases these exceptions directly involve archives. For instance, the copyright law of Finland allows archives to copy printed works on microfilm and it has been suggested that a similar provision be made for copying rare recordings on tape to ensure their preservation.

(c) Works Out of Copyright

Copyright lasts for a certain number of years only; the time of protection varies from country to country and can be different for different types of works. When copyright has expired, the work is in public domain and can be freely copied. Please note, however, that the rights of both the authors and the performers must have expired before this can be done. Early recordings are out of copyright in many cases.

The illegal copying of sound recordings continues to cause great losses to the record industry and it is easy to understand why the industry is very much concerned about copyright. Where sound archives are concerned, however, the record companies are usually quite helpful. Archivists who are uncertain about copyright matters, or who have specific problems regarding the copying of sound recordings, should first contact copyright organizations or representatives of the record industry in their own country. Certainly many problems may be solved in this way.