An Archive Approach to Oral History

An Archive Approach to Oral History

IASA Special Publication No. 1

by David Lance

Keeper of the Department of Sound Records,

Imperial War Museum London

in association with

International Association of Sound Archives

Association Internationale d' Archives Sonores

Internationale Vereinigung der Schallarchive.

Published 1978

IASA Members may also download a free PDF version. If you are not a Member, why not join IASA?

Table of contents

Forewords

Foreword by the Director of the Imperial War Museum,

Dr Noble Frankland CBE DFC

The Imperial War Museum exists to illustrate and record all aspects of modern warfare and collects every type of material bearing on this subject. These have included, since the Museum's foundation in 1917, films, photographs, documents, books, and works of art as well as weapons, uniforms, medals, equipment and other three-dimensional objects. Recently the development of sound recording and of oral history techniques has added a new dimension to this range of materials and one that is especially important to the Imperial War Museum. For it is now possible to secure permanent records of those servicemen and women and civilians who, for lack of inclination, opportunity, or literary skill, will leave no written records for the historians of the future to study. The participants in great historical events may be questioned about them and their experiences and opinions recorded in their own voices. Sound recording also adds to the range of different ways in which the public is able to gain access to the Museum's collections by using sound in exhibitions and in educational activities, through audio publications, and by contributing recordings to radio programmes - two programmes, Icarus with an Oilcan and The Loneliest Men have been compiled by the Museum's staff and broadcast by the British Broadcasting Corporation. Since 1977 the sound archive has been open to the public and copies of tapes offered for purchase. The Museum's Department of Sound Records, its newest collecting Department, was founded in January 1972. The Keeper, Mr David Lance, is also Secretary of the International Association of Sound Archives with which the Museum is pleased to be associated in publishing this guide to oral history technique.

Noble Frankland

Imperial War Museum

9th February 1978

Foreword by the President of the International Association of Sound Archives, Dr Dietrich Schüller

The International Association of Sound Archives was established in 1969. It exists to represent, focus and develop the work and interests of institutions and individuals professionally involved in the collection, preservation and dissemination of documents of recorded sound. Since its creation IASA has drawn together members associated with archives of music recordings; historical, literary and dramatic recordings; bio-acoustic and medical sounds; recorded language and dialect surveys; folklife and ethnological recordings; and many broadcasting organisations. The practice of oral history, which has developed with remarkable speed during the past two decades, has resulted in the creation of an important new category of sound archive that is now well represented within IASA. This work by David Lance is welcome as a useful source of practical information for all who are concerned with oral history and, particularly, with oral history sound archives. It is the first in a series of specialist publications which IASA hopes to sponsor. In making this publication possible the International Association of Sound Archives is glad to acknowledge the burden of authorship, preparation and printing which has been carried by the Imperial War Museum.

Dietrich Schüller

Phonogrammarchiv der Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften

13th January 1978

Preface and Acknowledgments

This publication is based on my experience of setting up and developing the oral history programme at the Imperial War Museum. Like some similar works it reflects the specialised interests and particular purposes of one institution. These cannot be directly relevant or applicable in all respects to the great variety of organisations and individuals in the field, many of whose interests and emphases are differently placed. It does, however, cover much ground and many problems which are common to all oral historians and provides a focus which is in some respects distinct from earlier comparable works.

I was initially motivated by Dr Rolf Schuursma - Editor of the Phonographic Bulletin (Journal of the International Association of Sound Archives) - to write An Archive Approach to Oral History. The interest of lASA in this field of activity exists for two reasons. First, because a growing number of the Association's member archives are creating and acquiring oral history recordings. Secondly, because IASA - as an association of professional sound archivists - is concerned that the substantial growth of interest in oral history should be accompanied by a corresponding degree of understanding about the importance and qualities of the resultant sound documents. This concern accounts for the space and emphasis given to technical matters in this publication.

The fact that this work appears as a publication sponsored jointly by IASA and the Imperial War Museum, is due to the interest and encouragement of Dr Christopher Roads (Deputy Director of the Museum) who was primarily responsible for the initiative which led to the establishment of the recording programme on which An Archive Approach to Oral History is based. It complements other publications which have come from the Museum and reflects the institution's longstanding efforts to encourage a multi-media approach to historical research.

While accepting full responsibility for the content of this publication, I should like to thank Roger Smither who, with Laura Kamel, wrote Chapter 7 on cataloguing and indexing. The technical sections could not have been compiled in their present form without the expert knowledge and contribution of Lloyd Stickells. Directly or indirectly, the influence of these and other Museum colleagues has also contributed to many of the practices described in the text. Margaret Brooks has played an important part in the development of our methods and Fiona Campbell helped to compile the bibliography.

David Lance

Keeper of the Department of Sound Records

Imperial War Museum

November 1977

1. Introduction

Before preparing this booklet on the practice of oral history, I seriously considered whether there was any need which could justify my adding yet another such publication to the already substantial and rapidly growing body of literature on oral history. Whether it does meet any need will only become known after the circulation of the work. There did, however, seem justification for such a publication as this.

A major justification is that all comparable existing texts are of American provenance. Those publications - among which the works of Willa Baum and William Moss are perhaps the best known1 - reflect oral history's mode of development in North America. There, the main preoccupation has been 'to obtain, from the lips of living Americans who have led significant lives, a fuller record of their participation ... in political, economic and cultural life.'2 By contrast the oral historian in Britain has very largely been concerned with the social history of urban and rural working class groups and communities: 'He moves among the generality of the population, noting and recording prejudices and reactions ... to garner human experience in all its richness'. 3 Different principles have produced different practices and some of these will be reflected in the following pages.

Thus, this work is intended as a practical reference source for those to whom the British experience may be more appropriate than the American model and - for more general interest - simply as a counterpoint to the other comparable publications available in this field.

This manual has also been compiled as a step towards the codification of disciplines which are of particular relevance to museums, libraries, archives and other collecting centres. One feature of oral history in Britain is that much of the important early work and nearly all of the published literature has been produced by university historians whose main concern has been with their own research and publication. As a result the bulk of the published commentaries have focused on those aspects of oral history that most naturally interest academic historians such as, for example, research methodology and the evaluation of oral evidence. With the growing involvement of libraries and archives (whether through the establishment of creative recording programmes or by way of receiving recordings and transcripts which others have produced), it is opportune to provide a publication that may be of practical value to collecting institutions which have to come to terms with the specialised housekeeping problems which apply to oral history materials.

So An Archive Approach to Oral History provides a body of professional method for oral history librarians and archivists. The practices which have been developed in my Department during the past six years may help to set standards and provide conventions which can eventually be developed into a code of professional practice of the kind which has been long established for the administration of traditional records.

A third consideration, in addition to the national and institutional factors, contributed to the compilation of this work. The importance which my Department attaches to the medium of recorded sound has fundamentally influenced many of the methods we have developed. This emphasis is not typical. In North America methods are - with important exceptions4 - still generally orientated to the production of the oral history transcript, which is widely held to be the product to which recording programmes should be geared. In Britain, the domination of the transcript is not nearly so strong but technical standards and knowledge here are also generally and unnecessarily low. Many individual practitioners and collecting centres are conscious that well-recorded oral history interviews have particular qualities and applications which can be exploited in various interesting and valuable ways. For those, whose main concern is the creation and administration of oral history sound recordings, this publication may be more useful than other works whose emphases have been differently placed.

Several sections of this manual are based on papers originally drawn up as working procedures for my Department. When the Department began its oral history programme in 1972 there were very few established professional practices sufficiently well suited to our needs to warrant imitation. 5 In nearly all cases, therefore, we designed and developed our own procedures, frequently revising and refining them in the light of growing experience and not a few false starts. The methods described in the following pages have stood up fairly well to the test of ten major recording projects in such varied fields as military, naval, air, industrial, agricultural, medical, welfare and art history. They are consistently applied in an archive which now holds more than three thousand recorded hours of material.

The theory of oral history has not yet been formed into a generally accepted orthodoxy. Perhaps it never should. Most authors in the field, however, make some attempt at definition and evaluation of oral history, and the present writer is also unable to resist the same temptation. A simple and probably uncontroversial definition is that oral history is formed from the personal reminiscences of people who were participants in or witnesses of the events or experiences they recount and - by present conventions - information which is obtained by interviewing methods and recorded verbatim by one means or another (though in practice now almost invariably on magnetic tape). Beyond this functional definition there are a number of differences of emphasis. For some practitioners oral history must be research directed; for others it must be archivally focused, in the sense of collecting generally whatever information informants may have to offer; some oral historians see the value of the information recorded as directly related to its proximity in time to the events covered; while others hold to the belief that the oral tradition communicates accurate and valid data across decades or even centuries. Such differences illustrate the range of approach and account for varying definitions.

Having briefly considered the method, what of the material? What is the status of oral history records and wherein lies their value among the various other classes of historical source materials? It will be argued that oral history records provide three major categories of information, which can be described as sensory, complementary and original. The concept of sensory information may not be recognised or considered as a characteristic of historical documentation (except perhaps by the media), but the oral qualities contained in sound recordings have their own special value and it is one which is distinct from the communication capabilities of any other record form. In this respect the essence of the information is in the medium which carries it, as well as in the information itself. Oral history's ability to affect the feelings as well as the intellect, gives an essentially human underlining to the facts that the recording also conveys. The value of such sensory information may be measured in relation to the degree of additional understanding of historical experience that the oral history record imparts. Above and beyond what can be discovered from other sources about the same experience, recorded sound carries its own unique dimension of information.

Oral history records are also of value in that they can be created and used to complement other record sources. In the field of biographical research, for example, historical gaps of interest and importance are frequently found which can be filled by using oral history methods to create records which otherwise could not be made available. Similarly, when research otherwise might have to be confined to using administrative documents, the personal and anecdotal characteristics of recorded interviews can provide flesh for the sometimes arid bones of history. In this respect it is apposite to quote a former Keeper of the Public Records who, in a similar connection, identified as limitations of Cabinet Office records that they are 'deliberately prepared objectively and impersonally, and designed to record agreement and not promote controversy; [but] behind many of the decisions [lie] tensions and influences which are not reflected in the official records'.6 The value of personal testimony for amplifying such records has been assessed by one of the outstanding historical writers of the 20th century in the following terms: '[history should be] tested by the personal witness of those who took part in the crises and critical discussions ... The more that any writer of history has himself been ... in contact with the makers, the more does he come to see that a history based solely on formal documents is essentially superficial'. 7

The third contribution of oral history is that it can open fields which otherwise would be closed to historians and, in this respect, provide information which is original in character for distinct subject areas. For studying many social and occupational groups which do not leave written records of their lives and work, oral history is a fundamental and sometimes the only tool. In terms of historical research, it is in this area that oral history can make its most substantial contribution.

For further information an important assessment of the value of oral evidence is available in various books by George Ewart Evans 8 and a continuing dialogue on oral history research methods can be found in Oral History. 9 Further definitions of oral history, assessments or oral evidence and aspects of methodology can be found in the publications listed in Chapter 13.

- Baum, W. Oral history for the local historical society; Nashville, Tennessee: American Association for State and Local History; 1969.

Moss, W. Oral history program manual; New York: Praeger Publishers; 1974. - Nevins, A. The gateway to history; New York: D. Appleton-Century; 1938.

- Marshall, J. 'The sense of place, past society and the oral historian' in Oral history, Vol. 3, No. I; 1975, p. 23.

- The Public Archives of Canada and the Provincial Archives of British Columbia are among the important exceptions to this rule.

- The School of Scottish Studies (University of Edinburgh) and the Welsh Folk Museum were two centres which provided inspiration if not - by virtue of their subject fields - practices directly suitable for emulation.

- Wilson, S.S. The Cabinet Office to 1945; London: H.M. Stationery Office; 1975,p.4.

- Liddell Hart, B.H. The real war; London: Faber and Faber; 1930, p. 10.

- Evans,G. Where beards wag all; London: Faberand Faber; 1970.

Evans, G. The days that we have seen; London: Faber and Faber; 1975. - Oral History is the journal of the British Oral History Society; for subscription and membership details contact Mary Girling, Department of Sociology, University of Essex, Colchester, Essex, England.

2. General principles

Oral history recording is practised in varied institutional settings. In libraries and archives oral historians have particular problems which are not shared by many of their university colleagues. Partly these problems arise owing to the novelty of the creative function , which is in contrast to the traditional collecting role of these centres. There are, however, more important and less transient difficulties than this. First, the subject range of collecting centres can be extremely wide. Broad based recording programmes require a correspondingly varied range of historical expertise that is rarely found in a single institution, let alone a single historian. Secondly, unlike the majority of university projects -which may be personal to a particular historian or funded by limited and short term budgets -institutional programmes will tend to be ongoing. Thus the primary problem and challenge for libraries and archives lies in sustaining a large number and a wide variety of well designed recording projects.

In responding to this challenge, oral historians in libraries and archives should recognise both their strengths and their weaknesses. Among their foremost strengths will be a detailed knowledge of what printed and documentary records are available in their collecting fields. The absence of traditional records will itself suggest the kinds of recording projects which should either be set up or at least investigated. There are usually well established communications between libraries and archives which can be used to establish whether such gaps in historical records are absolute, as opposed to being merely deficiencies in a particular collecting institution.

However, the records of most historical fields are deficient in some respects. While absolute gaps provide obvious paths to pursue, projects can also be based -even in well documented fields -on what the records do not tell historians. In the evaluation of existing record groups the training and experience of library and archive staff will be valuable and relevant.

So topic selection, the key to any soundly based recording programme, is a function which collecting centres are usually well qualified to carry out. However, the professional experience of librarians and archivists may have prepared them less well for the need to define objectives and otherwise prepare their selected projects Oil the basis of the most recent scholarship. Historians responsible for broadly based recording programmes in collecting centres seldom have the opportunity to develop their subject knowledge to a sophisticated degree in very many fields. So, even if they have considerable research experience, collaboration with appropriate subject specialists is probably the most prudent and an always valuable recourse in preparing any project.

Project preparation within professional collecting institutions should, however, take into account more than research criteria. Collecting centres do not exist solely for research. In a great many cases their main function is broadly educational and their main users the educated general public. Collecting and presenting materials as they are for non-specialists, their recording projects should also relate to the wide variety of interests which they exist to serve. Those who consider oral history to be purely a research method sometimes find it difficult to reconcile the function of reflecting the past with that of uncovering it. However, oral history does permit the pursuance of both ends without one necessarily damaging the other. The aim of oral historians in libraries and archives must be to ensure that their work actually does achieve this.

For the purpose of oral history recording the contradistinction between research and education arises because projects can be geared more towards one end than the other. Many collecting centres could validly organise their recording work on rather general subject lines, with the deliberate aim of producing material which will have the widest possible educational application. This would provide little original information. It can be argued, however, that very narrow research projects -of great value to a small number of scholars -may be of little practical value and use for the many other users whom libraries, archives and museums serve. On the other hand, not to raise with informants questions which might provide scholars with otherwise unrecorded information would be to miss important and perhaps unrecoverable opportunities for posterity.

If collecting centres are not to give the needs of one group of their users priority, where then are they to strike the balance? This can only be achieved by developing an approach to oral history which combines depth and breadth. The careful selection of project subjects in areas where oral evidence can make a significant contribution to historical documentation is essential. But while seeking to record original information, the approach should not be so esoteric as to preclude opportunities for collecting sound recordings which have a more broadly educational potential. In practical terms this means interviewing in a flexible way. We should not confine ourselves to investigating only prescribed research themes. Within the general subject area of the project, information should be recorded about any interesting events or activities which the informant participated in or witnessed.

The case for recording in breadth as well as in depth may also be made by contrasting oral history in the universities with recording projects in collecting institutions. University historians are generally using recording techniques in specialised fields of personal academic interest, as a means of collecting information primarily for _their own use. Libraries and archives rarely acquire materials with any comparably specific ends in mind. So, in the range of their recording, they should be able to adopt a more flexible approach. This practice is not only possible but politic. Experience administrators of any kind of reference collection know that public and research interests change. As libraries and archives are collecting for future as well as present generations, they should not be over influenced by current fashions.

The need for breadth and depth in collecting institutions is accompanied by a need for the known as well as the novel. Personal reminiscences which represent the common experience have a permanent value in the process of acquiring a real sense of history. Even when they add little to our knowledge of the past, they can contribute much to our understanding of it. Anecdotes are particularly valuable in that they most commonly achieve the profound sense of involvement which gives oral history recordings a strength of personal character unique among the various classes of historical documentation.

There are, however, inherent contradictions in a very flexible approach to oral history which have to be guarded against. For in seeking to meet all demands lies the danger that you may satisfy none. So flexibility requires not less preparation but more. It calls for a structured approach, so that within a disciplined plan interviewers are in fact able to move freely with purpose and effect. For by laying down fairly rigid research rules, the breaking of them will not only be a deliberate decision (or at least a conscious occurrence); it will also be constructive towards those ends other than pure research which a professional collecting centre should always have in mind.

As regards the scholarly use of oral history collections, how can the collecting centre best serve the academic researcher? Scholars will not be able to assess the nature and worth of oral evidence, or its relevance to their needs, unless each stage of its creation has been carefully documented (see also Chapter 3). The general aims of the collecting centre in carrying out a recording project, may be very different indeed from the purpose of the historian who eventually seeks access to the resultant material. So, along with the recordings and transcripts, the archive must also be prepared to furnish its users with the fullest details of the collecting methods which were used, as well as sufficient personal details of the informant for the scholar to be able to judge the quality of his source.

The principles suggested in this section as being particularly relevant to libraries and archives - or to the institutions in which such collecting centres may be set - have to be seen against the range of possible uses to which oral history material may be put (see also Chapter 12). Thus radio broadcasting and audio publications are realisable ends, offering attractive opportunities for the very wide dissemination of archive records. Within museums, and elsewhere for exhibition purposes, oral history recordings provide a display technique which is Singularly effective for reminding visitors that history is about people, as well as giving background and depth to the objects exhibited. To teachers, the scope for using recordings in the classroom is wide and, unlike most of the published audio packages which are available, oral history archives provide educationists with raw materials from which they can select and compile the aids they judge best suited to their particular needs. Scholarship has already been sufficiently served by oral history to make it unnecessary to re-emphasise the value of oral evidence in research and publication. Finally, the familiarity of the public with audio information and stimuli over several decades will undoubtedly offer many new opportunities for using oral history recordings in research and education. In this full range of exploitation lies the dividend which collecting centres should seek and this, in turn, underlines the need to develop a more archive centred methodology which both draws upon purely academic experience and adds to it.

3. Project Organisation

The organisational methods on which this section is based have been applied across a wide subject and chronological range. They can be adapted for much oral history research which is concerned with the history of particular social and occupational groups. In order to allow readers to relate the various phases of project management to specific examples it is convenient, however, to concentrate on a single project. The project used for illustrative purposes was concerned with the experiences and conditions of service of sailors who served on the lower deck of the Royal Navy between the years 1910 and 1922.

Preparation

The organisation of any project should be set within realistic research goals. Since oral history recording is dependent for worthwhile results on human memory, this fallible faculty must be accommodated by careful preparation. The planning of the project should, therefore, be based on as thorough understanding of the subject field (and of the availability of informants) as the existing records permit.

It is prudent, first, to fix a research period which is historically identifiable as being self-contained. In the lower deck project, for example, the so-called Fisher Reforms of 1906 altered several important aspects of naval life: the First World War stimulated further changes during the early 1920s; and the Invergordon Mutiny in 1931 was another watershed for Royal Naval seamen. The combination of these three distinct periods in a recording project, would have made it extremely difficult for sailors who served throughout them to avoid confusion on many details of routine life which, for research purposes, might be of critical importance. Three distinct periods of social change within a single career of professional experience are clearly difficult for informants to separate with few points of reference beyond their own memories. By setting the general limits of the lower deck project at 1910 to 1922, a reasonably distinct period of naval life was isolated as appropriate for oral history research.

The research problems which are created by rapid social change can seldom be eliminated entirely from oral history recording. It is for this reason that historically unsophisticated interviewing can result in information of uncertain reliability. Therefore, the project organiser's responsibility is to minimise the dangers implicit in such situations by his own common sense and historical sensitivity, and he should always apply the question 'Is this reasonable?' to the goals which he sets. Some practical examples of the application of this principle in oral history research are given overleaf.

The chronological scope of an oral history project should be fixed before any recording begins, bearing in mind the age of the likely informants as well as the historical character of the subject field. By the time the lower deck project began in 1975, men who saw service in the Navy as early as 1910 were in their eighties, and thus the opportunities for preceding this date were limited. This basic consideration affects all oral history recording. The informants who are actually available to be interviewed, also predetermine many of the topics which may be sensibly raised. Thus, owing to the slowness of promotion in the Royal Navy there was little point in introducing questions about, for example, conditions in petty officers' messes in 1910. Only informants into their nineties would have had the necessary experiences to be able to answer them. The chances of locating a sufficient number of interviewees of this great age, were sufficiently slight to preclude this and many similar topics -from being a practical aim within a systematic research project.

Similarly, the project organiser must take into account the structure of the particular group of people he is concerned with. For example, a battleship of the Dreadnought era - with a complement of some 700 men - might carry one writer (i.e. account's clerk) and one sailmaker. The odds against tracing such rare individuals more than fifty years after the events eliminated some aspects of financial administration and some trade skills aboard ship from the range of what it was likely to be able to achieve.

The selection of and possible bias among informants, are related factors which have to be appreciated. Between 1914 and 1918 the total size of the Navy increased threefold owing to the needs of war. A substantial proportion of those who served for hostilities only may not have accepted the traditional mores of regular lower deck life. At the end of a carefully organised and conducted project, the organiser had no clear idea of whether wartime personnel generally adopted the attitudes of those who had been in the service since they were boys, because the original selection of informants simply did not permit systematic investigation of their particular prejudices. An appropriate selection of sailors to be interviewed would have produced a representative sample of these kinds of informants and thereby provided suitable evidence from which conclusions about this particular question could be drawn. This obviously does not devalue the information for the purposes for which it was recorded, but it does eliminate the range of hypotheses to which this body of data is open. Thus, the project organiser must take into account the relationship between the subject matter of the project and his selection of informants and -at one stage yet farther removed from recording - this involves being clear about the kind of research evidence he is actually seeking to collect.

Specification

The list of topics which guided the interviewers' work in the lower deck project is given below, as one example of subject delineation in oral history research. The field of study was first broken down into the following main areas:

a Background and enlistment

b Training

c Dress

d Ships

e Work

f Mess room life

g Rations and victualling

h Discipline

i Religion

j Traditions and customs

k Foreign service

l Home ports

m Pay and benefits

n Naval operations

o Effects of the war

p Family life

q Post service experience

Each of these topics was examined in some detail, the extent and nature of which may be demonstrated by one example. Thus, in dealing with the subject of 'Discipline', the following questions influenced the interviewers' approach:

a. What was the standard and nature of discipline on the lower deck? Who influenced it? Did it vary much?

b. What were the most common offences? What were the most extreme? How were they punished?

c. Was the discipline fair? Was it possible to appeal effectively against any unfair treatment, if it occurred?

d. What was the lower deck's attitude to naval police? How much and what sort of power did they have? Did they ever abuse their authority?

e. What were relations like between the lower deck and commissioned officers, 'ranker' officers, NCOs and the Marines?

f. Was there any code of informal discipline or constraint on the lower deck? What kind of behaviour was considered unacceptable and how would it be dealt with?

g. Who were the most influential members of the lower deck? Was their influence based on any factors other than rank?

Application

While there can be no question that the purposes of oral history research need to be very carefully defined, the way in which project papers should be used is open to variation. Some important work has been done 1 in which listed questions are much more numerous and refined than in the above example and the resultant paper used in the form of a social research questionnaire. While such methods may serve the purposes of some historians, for the wider aims of collecting centres (see Chapter 2) formal questionnaires have not been found suitable. Partly this is because no questionnaire is sufficiently flexible to accommodate, in itself, the unexpected and valuable twists and turns of an informant's memory; and partly it is due to the fact that a questionnaire can become an obstacle to achieving the natural and spontaneous dialogue that is the aim of most oral historians.

But, short of a questionnaire, lists of topics can provide useful guidelines for interviewers to work to. The more interviewers there are engaged on a particular project, the greater becomes the need to ensure consistency of approach. As a device for obtaining such consistency, topic lists have a practical value throughout a recording project. Even with a project which is in the custody of one historian, the construction of a formal research paper is still valuable for reference purposes, because consistency is no less important and only somewhat more certain with one interviewer than with many, in the course of a recording project of any significant scale.

- The outstanding British example of this kind of approach is Dr Paul Thompson's (University of Essex) study of family life and social history in Edwardian Britain.

Monitoring

It is possible, simply by drawing the interviewers together and taking their reactions, to get an impression of the progress that has been achieved at various stages of the recording programme. However, for the effective monitoring of the project more systematic aids should be introduced. These are needed because the creation of oral history recordings usually far outstrips that of processing the recorded interviews. Cataloguing, indexing and transcribing generally lag so far behind recording that the customary aids which give access to the material are not available when they would be most useful for project control.

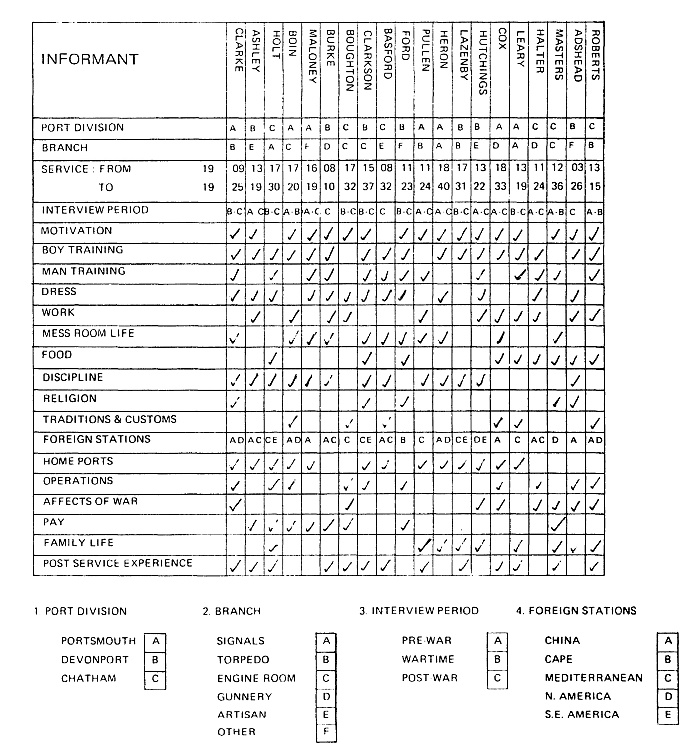

As an intermediate means of registering the project information as it is being recorded, simple visual aids can be designed which are appropriate to the work which is being carried out. In the case of the lower deck project the chart reproduced opposite was useful as such a tool. When projects are geared to preparatory research papers and control charts of the kind reproduced [under Documentation, next section] oral history recording can be effectively monitored and sensibly controlled. At the beginning of the project, the research paper represents the academic definition of the project goals. By careful application in the field academic prescription and practical possibility can begin to be reconciled. Thus, in the light of early interviewing experience, the list can be altered after some initial application. Certain questions may be modified, some removed or new questions may be introduced into the initial scheme, until a more refined and useful document emerges. Sensible alterations to the scope of a project cannot be made without a systematic approach of the kind that is implied in the formulation of a project paper.

As recording progresses, a chart of the information being collected permits the monitoring of the project's interim results. The value of the original topics - and their various divisions - should not be treated as inviolate until the work has run its full course. A common experience is that the collection of information in some subject areas reaches a point of saturation before many of the others. Such lines of questioning may be discontinued when there is reasonable certainty that their continuation would be unlikely to add significantly to the information that has already been recorded. The converse is also facilitated by a framework which permits the interim analysis of results. That is to say, areas in which the collection of information has proceeded less satisfactorily can more easily be singled out for greater attention.

Devices of the kind described above are usually essential in the effective management of oral history research. Unless the resources of the collecting centre are untypically lavish, there is usually no other means by which it can be established that the interviewing and recording is achieving the results which were originally sought. It is obviously necessary, through such methods, to be able to control the course of the project and to judge when it may be terminated.

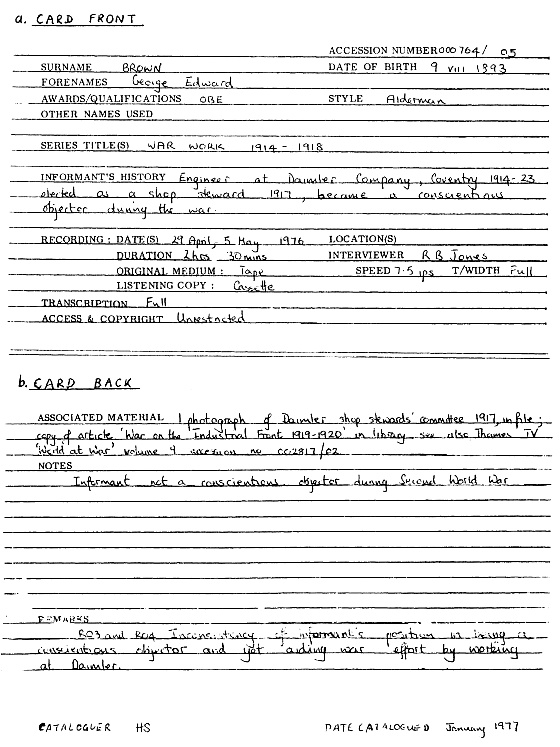

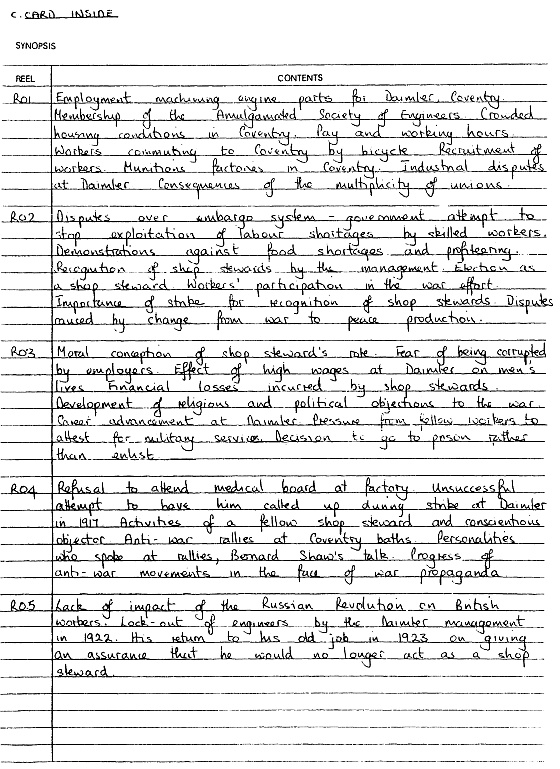

Documentation

For the proper assessment and use of oral evidence, the collecting centre should systematically record the project methodology. Without this background information the scholar may not be able to use appropriately the information which has been recorded. What were the aims of the project organiser? By what means were informants selected for interview? What was their individual background? How were the interviews conducted? How was the work as a whole controlled? The more information there is available to answer such questions as these, the more valuable oral history materials will be to the researcher and the more securely he can make use of them in his work.

A formal paper, of the kind recommended earlier, can tell the user a great deal about how the project was structured. A working file will be even more useful, if it reveals the way in which the work evolved (recording what changes were introduced at what stage in the development of the project). Such files should be maintained and regarded as an integral part of the research materials which may be needed by historians.

Individual informant files should also be accessible for research. They should contain biographical details of the informant and also be organised in such a way that the user can correlate tapes or transcripts with places and dates which are covered by the interview. In this respect, interviewers are in a uniquely valuable position to secure a documentary basis of the information they record. Often the informant's memory, photographic and documentary materials in his possession, reference sources and the interviewer's own subject expertise, can be combined to formulate quite a detailed chronology. This will support and give background to the recorded interview.

Similarly, the interview itself should be used as a means of establishing the kind of background information that will give additional significance to the information the informant provides. Thus, in addition to the specific project information the interviewer is seeking, he can with advantage also record details of the informant's place of birth and upbringing, his family background, economic circumstances, educational attainments, occupational experiences and so on.

Much that an informant says during the course of an interview he may wish to correct, amend or amplify subsequently. No documentation system would be complete without providing him with the means so to do. The opportunity to listen to or read the completed interview often provides the informant with a considerable stimulus to add to the information which has already been recorded. Once committed to an oral history interview, most informants feel the need for historical exactitude. Collecting centres can maintain their transcripts in pristine condition, whilst also giving informants full opportunity to supplement with written notes the information they have already given, and filing such notes along with the final tapes and transcript.

4. Interviewing

Oral history interviewing approximates to many kinds of situations in which one person is seeking to obtain information from another. In other words it is not a scientific technique (although it should be a systematic one) for which there are many fixed rules. A successful interviewer will develop his own methods and the most that a publication like this can hope to provide will be a few general guidelines.

More useful than any guidelines, however, is sensitive reviewing by the interviewer of the work which he has actually done. Potentially good interviewers will recognise many of the mistakes that may occur in their first interviews and be able to make the appropriate changes in their subsequent work. Those who lack this facility are unlikely to make good interviewers. The benefits from reviewing recordings will be greater if the study and analysis of the recorded interviews is a shared experience. Interviewing is commonly an emotional process from which the interviewer cannot entirely disassociate himself. (It would, in any case, be counterproductive for the interviewer to try to eliminate his commitment to the interview because it is on this personal level that much of his effectiveness will depend.) But it is important that he should have a thorough understanding of how he functions in an interview situation and how his informants react and relate to him. To achieve this the observations of experienced colleagues, who can bring greater detachn1ent and objectivity to the reviewing process, are particularly valuable.

It is helpful in oral history that interviewing is carried out within a clear historical framework; for when the aims are clear the achievements can be the better assessed. The most effective test of oral history interviewing is whether or not it is producing appropriate results. If the interviewer has been successful in these terms then this, more than his observance of all the approved conventions, is the ultimate criterion by which his work must be judged.

Having said this, the following guidelines may nonetheless be instructive:

Aims

The purpose of oral history interviewing and recording is to collect interesting and significant information by questioning men and women about their personal experiences within prescribed subject areas. Interviews should be based mainly on activities or events in which informants were directly involved. Opinions and attitudes may also be of interest and value, provided they generally derive from some personal knowledge on the part of the informant. Completely unfounded views are unlikely to be useful, unless the particular oral history project has some special purpose.

Interviews may often provide original information; they should always produce interesting reminiscences. The application of these two criteria is the best test of whether an interview has been successful or not.

Preliminary Interviews

For some kinds of oral history interviews preliminary meetings are unnecessary and can prove to be a positive disadvantage by taking the initiative from the interviewer. In recording well known politicians, for example, the historian is in any case generally able to find from written sources sufficient information about the informant's life and career to identify in advance of an interview the relevant and worthwhile subjects for discussion. The case of most informants from working class backgrounds is significantly different. Here the main and sometimes only source about the research field and the particular individual's place within it, is oral. Thus there are usually few points of reference apart from the informant's memory from which the interviewer can satisfactorily prepare himself. So, for the purpose of structuring the interview in a way which will obtain the most valid and valuable contribution each person can make, a preliminary interview is generally useful in providing the basis for successful subsequent recording sessions. The processes of research interviewing and recording methods are also sufficiently novel to unsophisticated informants that their introduction to them in a gradual fashion is a prudent and beneficial course.

The preliminary interview, therefore, has four main purposes:

- To enable the interviewer and informant to get to know each other and thereby create the appropriate atmosphere for a relaxed and trusting dialogue.

- To give the interviewer insight into the personality of the informant so that he can adjust his approach the questions he asks and the way he puts them to the individual needs of each informant.

- To provide the interviewer with adequate factual information about the informant's background and experiences so that he can structure the recorded interview in a sensible, well informed and appropriate way.

- To enable the interviewer to decide whether the potential informant is worth recording or not. Contributors should not be discarded lightly: but there is no point in pecording them unless they have useful information to give and are reasonably well able to articulate it.

If the preliminary interview has been conducted with care the subsequent recording sessions will have a real sense of purpose and direction.

Some oral historians regard preliminary interviews as anathema and most commonly argue that they rob the subsequent recordings of much of their spontaneity. It has to be acknowledged that sometimes the first account of a particular event is the best one. But the spontaneity of the overall interview is not significantly reduced provided the first recording session does not follow too closely on the preliminary meeting (a gap of between one and two weeks seems to work best). If the loss of freshness in a small proportion of the recording is a regrettable price which sometimes has to be paid, there are clear compensating advantages from preliminary interviews which can be identified. The opportunity they provide to reflect on and study the range and detail of possible questioning, can result in many questions being put which might not have occurred to the interviewer in the heat of a recording session which was not so prepared. It can be argued that follow-up interviews serve the same purpose; but they do so only at the expense of producing a very disjointed recording in which related parts need to be subsequently brought together either by editing or more elaborate cataloguing.

Generally, the degree of useful information in a recording is in direct proportion to the amount of interview preparation that has been carried out. Preparation which is also related to a prior appraisal of the informant's capabilities will usually result in recordings of greatest substance and economy. An undisciplined interview, on the other hand, will produce recordings and transcripts which are difficult and time consuming to organise or use as well as being extremely expensive products. A heavy cost may have to be paid in cataloguing and transcribing for that first spontaneity which too easily deteriorates into superficial meanderings.

Recording Sessions

The ideal oral history recording would be a natural and spontaneous unfolding of all those parts of an informant's life story which have a connection with the research field being studied. Natural and spontaneous they will often be; but it is the rare and treasured exception when interviews unfold. More typically they are drawn out through good preparation and hard work. Interviews most conveniently follow a chronological pattern; start at the beginning and work systematically through the period which the particular project is concerned with. This helps to ensure that most of the informant's relevant experiences are covered and also correlates particular details with specific periods and places.

Do not hurry the interviewing process. The pace of an interview depends mainly on the informant's personal capacity; the length depends entirely on the amount of useful information he has to give. There should be no other personal factors to consider in deciding how much time to devote to each informant.

Keep your questions as short and simple as reasonably possible and only ask one at a time. When you are reaching the end of a reel avoid questions which are likely to elicit a lengthy response, so that the informant does not lose the thread of his answer during a reel change. Do not interrupt the informant while he is speaking or interpolate 'yes', 'I see' and other noises to encourage the speaker and reassure him of your interest and attention. Appropriate facial expressions serve this purpose equally well and do not spoil the recording with extraneous noises.

Interviewing Sins

- Questions which are unnecessarily long

- Questions which are not clear

- Questions, too frequently, which are answerable by 'yes' or 'no'

- Combining several questions into one

- Interrupting a speaker with a secondary question before he has finished answering the first

- Failing to press a question which has not been fully or satisfactorily answered

- Seeking, too often, for opinions and attitudes (particularly without establishing any factual basis for them)

- Missing opportunities for follow-up questions which are 'invited' by earlier answers

- Not asking for specific examples to illustrate general points which an informant has made

- Jumping to and fro between one subject and another, or one time period and another.

The final transcript of a recorded interview can provide revealing evidence about how effectively the interviewer has done his job. For similar reasons as reviewing the recordings, the transcript merits study. Perhaps the clearest indication that preparation was inadequate or the interviewer somehow lost his way, is to be found in the balance between questions and answers. If the interviewer occupies a disproportionate amount of transcript text, then it is likely that something has gone amiss!

5. Recording

If an interview is worth recording, it is worth recording well. A poorly recorded interview can be transcribed but it can be used for little else. Radio, television and commercial records have accustomed present generations to a fairly high standard of recorded sound. This has also set a standard for any oral historians who wish to use their tapes for the various audio applications which are described in Chapter 12. Even if these uses are not of primary concern, interviewers should take the trouble to use their tools efficiently. Given that recording techniques for the usual interview situation are perfectly straightforward, if becomes almost as easy to make a good recording as a bad one!

Recording Environment

The biggest problem when recording in people's homes is persistent extraneous background noise. If informants live on a busy road or near an airport, for example, there is usually no way in which a good quality recording can be made. Sometimes moving to another room in the informant's house will enable you to get far enough away from the source of the extraneous noise to make a satisfactory recording. Otherwise the only alternatives may be to try to move to the home of a neighbour, friend or relative, or to ask the informant to come to the collecting institution if better facilities are available there.

A good many minor extraneous noises can be and should be silenced. Clocks, fluorescent tubes, refrigerators and other electrical appliances are most common and can usually be stopped or moved. Dogs and budgerigars should also be 'silenced'. To deal with the noise problem interviewers must carefully assess the environment. Listen! If you can hear noises the microphone can too and they will always sound more distracting and prominent on the recording than they do to the interviewer at the time.

The best rooms for recording are those that contain a lot of soft furnishings and such things as curtains, carpets and rugs. This will usually be the living room. Technically, the bedroom is probably the next best recording area! Rather bare rooms, with a lot of hard reflective surfaces will give the recording an echoey, bathroom-type sound and should be avoided if possible.

Microphones which can be clipped to the informant's clothing are best suited to oral history interviewing requirements (see also Chapter 9). Apart from being small, and therefore unobtrusive, they permit almost complete flexibility in the matter of seating arrangements. You should place the informant and yourself in the most 'natural' setting. If the informant has a favourite or usual chair, that is where he should sit. Place yourself in a position where you are comfortable and can make good eye contact with him. In other words, you should arrange a social disposition and avoid 'staging' the interview.

If you are using a table standing microphone, the easiest way to work is to set up the microphone on a table (over which there is a table cloth or some other soft material) at which the interviewer and informant can sit on fairly upright chairs. Try to avoid easy chairs as these tend to throw the speaker too far back from the microphone to obtain a good recording level.

The recorder itself is best placed out of the informant's view (and never on the same table as the microphone), but in a position where the interviewer can see it easily. This is arranged most simply by the machine and the informant being on the opposite sides of the interviewer, so that his body serves as a screen.

Thus, in selecting your recording environment, there are three main considerations:-

a. Extraneous noise

b. The room acoustic

c. The convenience and comfort of informant and interviewer

Often you will have to compromise, because it will not be possible to meet all three conditions. In such cases, (a) and (c) above are the most important considerations for getting a good quality recording.

Microphone Placement

A clip microphone should be attached to the most stable appropriate part of the informant's clothing, so that it cannot swing in response to movements of his body. Thus, a jacket lapel is to be preferred to a tie. The microphone should be placed some six inches (15 centimetres) from his mouth; that is about breast pocket level. Secure the informant's microphone cable in some appropriate way (e.g. by tucking it into the corner of his chair) and make sure, at all costs, that he does not handle it while you are recording.

A table standing microphone should be placed not farther than eighteen inches (45 centimetres) from the informant's mouth. Interviewers should try to get an equal recording balance between the interviewer and the informant, which may require adjusting the speakers' positions relative to the microphone to compensate for the one with the weaker voice. Remember, however, that the informant is more important than the interviewer and at least ensure that you are getting a good recording level on his voice. Do not aim the microphone at the informant. You will get better results (and find it easier to make good eye contact with him) by placing the microphone so that you are both speaking across it.

Using the Recorder

In selecting the recording speed one factor to bear in mind is that the slower the speed the lower the absolute recorded frequency range, and the higher the relative tape hiss level. That is to say that at the slow speeds of 1 7/8 i.p.s. (4.75 cm/sec) and 15/16 i.p.s. (2.4 cm/sec) you may fail to record the higher frequencies of the voice on some machines. As the hiss level increases noticeably at these speeds, this produces an extraneous audible noise at the same time. These two related factors working in combination can produce an unpleasing recording. With a modern machine and an appropriate tape these dangers will usually be avoided and spoken word recordings of a high standard should be achieved at speeds of 3¾ i.p.s. (9.5 cm/sec) and above.

The use of automatic recording level control devices found on many recorders is not generally recommended. There is a case for using them with informants whose voice levels rise and fall dramatically or with a fixed microphone for interviewees who are constantly moving their positions relative to the microphone. But as they can have the result of making certain words sound clipped and may also cause a general and audible rise and fall effect on the recording these automatic controls should only be used under exceptional circumstances.

Interviewers should set the recording level manually, so that at the 'peaks' of the informant's speech the meter level indicator is just below the 100% or zero mark. This means that for much of the interview the needle will probably only be registering in the lower regions of the meter and never - well hardly ever -in the section which is usually marked in red. Set the recording level while social pleasantries are being exchanged and then apart from the occasional glance concentrate on the informant. If the interviewer has made the initial adjustment carefully, then most reasonable quality modern tape recorders will take care of the rest.

Before using the equipment in the field experiment with it at home or in the office. This teaches the interviewer what his recorder is capable of and how to get the best results from it. Such familiarisation exercises will also give the operator confidence in his own competence. The lack of such confidence in the interviewer can have a similar effect on the informant.

Administration

A key point during recording is to speak the informant's name and the appropriate reel number onto the tape and to write the corresponding references on the carton. Neglect of this common sense practice can make a nonsense of transcripts and catalogues.

6. Transcribing

The practice of reproducing the content of a recorded interview in the form of a typescript, thereby creating the oral history transcript (a hybrid that is neither a genuinely oral record nor truly a written document), has resulted in an apparently endless debate about the relative status of these two formats. To the extent that it focuses attention on how to present an essentially verbal record as accurately as the written format permits, the debate should be of interest and value to all collectors and users of oral history materials. However, claims that the transcript is the primary oral history document ascribe to it a character which the most discriminating processing methods can never achieve. The only form in which the full content and quality of oral information can be reproduced is that in which it is recorded. It is in the spoken word, not the written, that the oral history interview is encapsulated.

Given that the average speed of reading is about three times as fast as the average rate of speaking (and therefore of listening, since there are as yet no generally available systems for fully redressing this imbalance while retaining speech audibility) the value and importance of the transcript obviously lies in the convenience of access it permits to the content of oral history interviews. While the transcript has no other major advantage over the recording, this one alone is a sufficient justification for its existence, and a sufficient guarantee that most collecting centres which have the means will endeavour to transcribe as many of their interviews as possible.

Selection

If collecting centres do not have the resources to transcribe their recordings, effective cataloguing and indexing (see Chapter 7) is of paramount importance, as it provides the sole facility for retrieving information which has been recorded. Other institutions either may not have the means to transcribe all the recorded interviews they collect, or they may feel that not all of their recordings merit this costly process. In all cases where a measure of selection is necessary, the following criteria can be used. Transcription may be recommended when:

- The fame or historical Significance of the informants suggest that there will probably be a demand for access to their interviews.

- More than 50% of the content of a particular interview is informative as opposed to impressionistic in character.

- There are clearly outstanding parts, though amounting to less than 50% of the whole interview, in an otherwise unexceptional recording (then the appropriate reels may be specifically recommended for transcription).

- The quality of the interview, as a sound recording, is sufficiently lively and interesting to indicate that it has potential value for use in, for example, educational or broadcasting programmes.

It does not follow from the above that the lack of a transcript necessarily indicates a poor interview. Interviews which are not selected for transcription may be those which contain a higher degree of general than specific information; those in which there is more opinion than illustration; and those where the informant is less articulate or overly discursive. Such interviews may well contain extremely valuable information even though - for one reason or another - it is not well enough presented by the informant to justify the cost of transcribing.

Transcribing Policy

One major factor which affects transcribing policy is the relative status which the particular institution gives to its recordings and transcripts. The Department on whose methods An Archive Approach to Oral History is based unequivocally takes the position that the sound recording is the primary oral history document. In application, the main consequence of this viewpoint is that the resultant transcripts contain the facts of the interviews but are not overly concerned with their 'flavour'. Many conversational characteristics are deliberately excluded from the transcript and those users who seek or need the verbal idiosyncrasies of oral history are directed to the sound recordings.

Each collecting centre must take its own decision on this general principle and, following from it, what scale of its resources tp allocate to the transcribing programme. The investment in this work -if it is undertaken at all -will, however, always be substantial because transcribing is by its nature time consuming, labour intensive and therefore costly. Thus the area for individual choice lies not in whether transcribing may be done cheaply or expensively, but in making the programme more or less expensive. What then are the relevant considerations? The most fundamental one is implicit in the previous paragraph, but there are many others. Should the first typescript be the final product? If corrections are made to it should they be made in manuscript or must they be in typescript? If in typescript, should the corrections be made on the original transcript or should this be retyped? Should you permit informants to amend their original statements and, if you do, should the entire text be retyped to accommodate them? If common subjects are discussed in different parts of the interview should these be brought together in the transcript? By answering all such questions collecting institutions will eventually find the balance between what they prefer and what they can afford.

When the collecting centre has formulated its policy it is important that the preferred practices are laid down in the form of detailed written directions to which the typists can refer. This provides a clear basis for their work: the most economic means of achieving consistency: and, above all, it ensures that extremely important decisions are taken by the historian and not by the typist. In this lies the best guarantee that the content and construction of the interview will be faithfully reproduced.

General Practice

The task of the typist is to produce an accurate typescript of the interview and by the appropriate use of sentences, paragraphs and punctuation - to make it as literate a document as possible without altering the words or sense of the speakers. Thus the informant's choice of words should always be retained; 'I were' should not be changed to 'I was' or 'don't' replaced by 'do not'. Similarly, certain conventions of the written word, such as not beginning sentences with conjunctions, need not be observed when typing the spoken word. The most loyal printed facsimile of an oral record would contain phonetic spellings and, by this and other means, take account of unusual words or forms of words which are due to dialect or accent. For purely historical research, however, such methods are unnecessary and, in most cases, known words are best given their conventional spellings.

Although the object is to transcribe the interview as accurately as possible, there are certain conversational characteristics which can be excluded from the transcript. False starts, such as 'it was in ... no it wasn't ... I remember now ... it was in the autumn of 1916', may be ignored and only the informative section of the recording need be transcribed. Repetitions may often be left out of the transcript, while 'ums' and 'errs', slips of the tongue, insignificant mistakes, and uninformative interjections are among the features of normal speech that may appear on the recording but can also be ignored as they would add nothing of substance to the typescript of the interview.

As there are aspects of a recorded interview which need not be carried over onto the typescript, there are also additions to it which may be usefully made in order to clarify the meaning or structure of what has been said. If, for example, there is a distinct pause in mid-sentence it may be helpful to indicate the speaker's hesitation by some clear convention such as three spaced dots. Suitable linking words may be added to the text where the recording is inaudible to the typist and either the informant or the interviewer feels able to provide the sense of the missing piece. In such cases, however, the readers should be warned that the inserted words are additions by placing them in square brackets. A similar situation sometimes occurs when the informant anticipates the interviewer's meaning and starts answering a question before he has completed it. The response can lose much of its pertinence if the reader is not also given the full question and, again, the interviewer should provide at least the sense of what the typist may not be able to hear.

In their general construction, transcripts should conform to the accepted rules and conventions of written language. These, however, may be variously applied in processing oral history interviews and a great many detailed decisions therefore have to be taken in order to establish a clear house-style (in this process consistency is usually more important than any particular practice). For example, should the speaker's qualifications or parentheses be indicated by placing them within brackets or by inserting hyphens before and after the appropriate piece? Should pauses in speech or unconc1uded sentences be represented by dots or by dashes? When direct speech has to be indicated are single or double inverted commas to be preferred and how do you then distinguish between direct speech and quotations? If magazines, bocks, newspapers or song titles are referred to, which of the conventions among the various possibilities (underlining, inverted commas, capitalisation) are to be employed in each case? When numbers are mentioned, are they to be typed in full or in numerals and where numerals are preferred are there occasions when Arabic or Roman figures might be used to distinctive advantage?

It will be clear from such examples that many transcribing conventions will not be based on absolute rules but, often, on preferences between equally serviceable alternatives. It will also be noted that the written representation of the spoken word makes considerable demands on the number of available conventions and that this necessitates very careful consideration and selection among the options for each case. This should under1ine the need for a set of formal transcribing rules which the typists should consistently app1y. To give one more example, all the possible cases where complete words or first letters might be capitalised should be prescribed. Without clear guidelines imagine the various forms in which the following piece might be typed: 'Life aboard HMS TIGER (Tiger) was my worst experience of navy (Navy) discipline and in the Engine Room Branch (engine room branch) the petty officers (Petty Officers) really ruled it over the stokers (Stokers). There was a Chief Petty Officer (chief petty officer) Jones in Number 2 Boiler Room (number two boiler room) who wielded a real rod of iron. This sort of thing could make you hate the service (Service)! The list of questions which have to be considered and answered in order to regularise transcribing practice is not endless but it is certainly long and cannot - or at least should not - be avoided.

The layout of the transcript also raises important considerations. Presentation and format not only have a bearing on the good appearance of a document which is produced at considerable cost; they are also instrumental in making the text as clear as possible and the typescript convenient to use. The options in this field are again quite numerous. Margins (on all Sides), page numbers (and - for correlation - reel or cassette numbers), informant's and interviewer's names (or initials), overleaf keywords, spacing and alignment should therefore all be standardised.

The main purpose of this chapter is to identify some of the main problems and pitfalls which arise in the process of transcribing oral history recordings. A specific code of practice has not been laid down because it is to be expected that collecting institutions will formulate their own conventions in the light of individual preference and resources. But although practice may vary the problems are common. Every transcribing programme therefore needs to be based on a detailed set of rules which are consistently applied if the programme is to be systematically effective. For detailed instructions based on the preferred (and exacting) transcription methods of one experienced centre, reference may be made to Transcribing and Editing Oral History by Willa Baum (Nashville: American Association for State and Local History; 1977).

7. Cataloguing and indexing (Roger Smither with Laura Kamel)

Introduction

Oral history recordings are exceptional among reference materials in that their contents are not amenable to 'browsing'. Researchers and cataloguers may 'dip' into a book or flip through a photograph album. There are, however, no real alternatives to playing a sound recording on appropriate equipment at the correct speed all the way through. It is true, of course, that an oral history transcript is as accessible as any other comparable documents, but since the audio dimension of oral history carries a significant part ,of its message adequate documentation has to be provided by way of finding aids for access to the original medium.

The documentation discussed here is, primarily, that which the archive maintains on its own premises for its own purposes, covering the entire collection. Material extracted from the central source for publication is of secondary importance in this context and will not be considered in this section. The documentation which it is normally considered essential for an archive to supply comprises a catalogue, with entries describing each separate item in the collection, and an index or several indexes in which the user may look up the topics which match his interest and be directed to items in the collection relevant to those topics. The index should be regarded more as a key to the catalogue than to the collection itself. Although the researcher who finds only one reference in the index suiting his needs may as well go directly to the item indicated, the researcher who is offered several apparently suitable recordings by the index should use the catalogue, with its description of the nature and context of the proferred items, as a means of refining his short list before progressing to listening to tapes. Provision of transcripts may help the process of refinement still further.

What information should be conveyed by the entries in this catalogue which is so central to an archive's documentation, and does there exist a proven acceptable system which would spare the archivist the task of evolving his own? The staff of an oral history archive asking these - questions will find the answers overlap. There are several extant cataloguing systems, and any or all of them repay examination; they all, naturally, also stipulate what information is to be provided. It is, however, inevitably true that most extant library cataloguing systems have been designed solely or primarily for book collections. The cataloguer of oral history recordings may find serious discrepancies between what an existing system offers and what his collection needs. Typically, a book catalogue entry looks for a title, a statement of authorship or responsibility and publication details. The cataloguer handling recorded interviews will find such labels inappropriate to his sources and, although the conventions may be forced to meet his needs, the results may please no one. The available 'standard' library package may well not provide a solution with which a conscientious archivist will be satisfied.

As people do not usually talk in the same way as they write, similar difficulties may be found in adapting established indexing or classification systems to the needs of an oral history archive. An even more serious difficulty arises because most oral history collections are set up with a specialist subject or regional emphasis. As a result they will usually be too specialised for established general systems and too generalised for existing specialist systems. For example, the Universal Decimal Classification system (UDC) covers 'the whole field of knowledge' but consequently offers little space for any specialised single interest. An archive of labour history would find that 'Labour, Work and Employment' is subsection 331 of section 33 (‘Political Economy, Economics') of UDC's primary division 3 (‘Social Sciences'). While a specialised archive would leave large portions of the classification system unused, its cataloguers and researchers would be obliged to pursue references through several digits and 'auxiliaries' to achieve a full description, a task they might find burdensome and inconvenient. Conversely, a specialist classification system, such as the Engineers' Joint Council Thesaurus of Engineering Terms, may go into too much detail to be of use in similar circumstances, besides failing to cope with the many peripheral topics about which informants may be expected to talk,

A further difficulty in indexing is implicit in the nature of the task. Whereas cataloguing may be described as the objective description of an item in a collection, indexing involves subjective evaluation of what is significant about that item. The evaluation, moreover, must attempt both to reflect a collecting organisation's own policy and to anticipate the needs of future users. The chances of finding a system evolved by a third party that will adequately meet the requirements of both archive and user are s1ender. For any or all of the above reasons, the cataloguer may be compelled to enter on the complex task of devising an indexing system for his archive from scratch.

The remarks made in the preceding paragraphs should not, of course, be read as a rejection of all the work that librarians and archivists have already done. They seek only to caution the creator of a new oral history collection against accepting that anyone has already done all the necessary work for him. Of course, if he can find an adequate extant system, he should use it. Equally, if his collection is part of a larger library or an organisation which already has an adequately functioning single system covering its other collections, he will obviously find substantial advantages in joining in as far as possible with the methods of his colleagues. This chapter may help some cataloguers to evaluate the systems they are offered and to identify those changes on which they feel they should insist. For the less fortunate, the chapter may provide a starting point for their own design work.

General Principles