3. Project Organisation

The organisational methods on which this section is based have been applied across a wide subject and chronological range. They can be adapted for much oral history research which is concerned with the history of particular social and occupational groups. In order to allow readers to relate the various phases of project management to specific examples it is convenient, however, to concentrate on a single project. The project used for illustrative purposes was concerned with the experiences and conditions of service of sailors who served on the lower deck of the Royal Navy between the years 1910 and 1922.

Preparation

The organisation of any project should be set within realistic research goals. Since oral history recording is dependent for worthwhile results on human memory, this fallible faculty must be accommodated by careful preparation. The planning of the project should, therefore, be based on as thorough understanding of the subject field (and of the availability of informants) as the existing records permit.

It is prudent, first, to fix a research period which is historically identifiable as being self-contained. In the lower deck project, for example, the so-called Fisher Reforms of 1906 altered several important aspects of naval life: the First World War stimulated further changes during the early 1920s; and the Invergordon Mutiny in 1931 was another watershed for Royal Naval seamen. The combination of these three distinct periods in a recording project, would have made it extremely difficult for sailors who served throughout them to avoid confusion on many details of routine life which, for research purposes, might be of critical importance. Three distinct periods of social change within a single career of professional experience are clearly difficult for informants to separate with few points of reference beyond their own memories. By setting the general limits of the lower deck project at 1910 to 1922, a reasonably distinct period of naval life was isolated as appropriate for oral history research.

The research problems which are created by rapid social change can seldom be eliminated entirely from oral history recording. It is for this reason that historically unsophisticated interviewing can result in information of uncertain reliability. Therefore, the project organiser's responsibility is to minimise the dangers implicit in such situations by his own common sense and historical sensitivity, and he should always apply the question 'Is this reasonable?' to the goals which he sets. Some practical examples of the application of this principle in oral history research are given overleaf.

The chronological scope of an oral history project should be fixed before any recording begins, bearing in mind the age of the likely informants as well as the historical character of the subject field. By the time the lower deck project began in 1975, men who saw service in the Navy as early as 1910 were in their eighties, and thus the opportunities for preceding this date were limited. This basic consideration affects all oral history recording. The informants who are actually available to be interviewed, also predetermine many of the topics which may be sensibly raised. Thus, owing to the slowness of promotion in the Royal Navy there was little point in introducing questions about, for example, conditions in petty officers' messes in 1910. Only informants into their nineties would have had the necessary experiences to be able to answer them. The chances of locating a sufficient number of interviewees of this great age, were sufficiently slight to preclude this and many similar topics -from being a practical aim within a systematic research project.

Similarly, the project organiser must take into account the structure of the particular group of people he is concerned with. For example, a battleship of the Dreadnought era - with a complement of some 700 men - might carry one writer (i.e. account's clerk) and one sailmaker. The odds against tracing such rare individuals more than fifty years after the events eliminated some aspects of financial administration and some trade skills aboard ship from the range of what it was likely to be able to achieve.

The selection of and possible bias among informants, are related factors which have to be appreciated. Between 1914 and 1918 the total size of the Navy increased threefold owing to the needs of war. A substantial proportion of those who served for hostilities only may not have accepted the traditional mores of regular lower deck life. At the end of a carefully organised and conducted project, the organiser had no clear idea of whether wartime personnel generally adopted the attitudes of those who had been in the service since they were boys, because the original selection of informants simply did not permit systematic investigation of their particular prejudices. An appropriate selection of sailors to be interviewed would have produced a representative sample of these kinds of informants and thereby provided suitable evidence from which conclusions about this particular question could be drawn. This obviously does not devalue the information for the purposes for which it was recorded, but it does eliminate the range of hypotheses to which this body of data is open. Thus, the project organiser must take into account the relationship between the subject matter of the project and his selection of informants and -at one stage yet farther removed from recording - this involves being clear about the kind of research evidence he is actually seeking to collect.

Specification

The list of topics which guided the interviewers' work in the lower deck project is given below, as one example of subject delineation in oral history research. The field of study was first broken down into the following main areas:

a Background and enlistment

b Training

c Dress

d Ships

e Work

f Mess room life

g Rations and victualling

h Discipline

i Religion

j Traditions and customs

k Foreign service

l Home ports

m Pay and benefits

n Naval operations

o Effects of the war

p Family life

q Post service experience

Each of these topics was examined in some detail, the extent and nature of which may be demonstrated by one example. Thus, in dealing with the subject of 'Discipline', the following questions influenced the interviewers' approach:

a. What was the standard and nature of discipline on the lower deck? Who influenced it? Did it vary much?

b. What were the most common offences? What were the most extreme? How were they punished?

c. Was the discipline fair? Was it possible to appeal effectively against any unfair treatment, if it occurred?

d. What was the lower deck's attitude to naval police? How much and what sort of power did they have? Did they ever abuse their authority?

e. What were relations like between the lower deck and commissioned officers, 'ranker' officers, NCOs and the Marines?

f. Was there any code of informal discipline or constraint on the lower deck? What kind of behaviour was considered unacceptable and how would it be dealt with?

g. Who were the most influential members of the lower deck? Was their influence based on any factors other than rank?

Application

While there can be no question that the purposes of oral history research need to be very carefully defined, the way in which project papers should be used is open to variation. Some important work has been done 1 in which listed questions are much more numerous and refined than in the above example and the resultant paper used in the form of a social research questionnaire. While such methods may serve the purposes of some historians, for the wider aims of collecting centres (see Chapter 2) formal questionnaires have not been found suitable. Partly this is because no questionnaire is sufficiently flexible to accommodate, in itself, the unexpected and valuable twists and turns of an informant's memory; and partly it is due to the fact that a questionnaire can become an obstacle to achieving the natural and spontaneous dialogue that is the aim of most oral historians.

But, short of a questionnaire, lists of topics can provide useful guidelines for interviewers to work to. The more interviewers there are engaged on a particular project, the greater becomes the need to ensure consistency of approach. As a device for obtaining such consistency, topic lists have a practical value throughout a recording project. Even with a project which is in the custody of one historian, the construction of a formal research paper is still valuable for reference purposes, because consistency is no less important and only somewhat more certain with one interviewer than with many, in the course of a recording project of any significant scale.

- The outstanding British example of this kind of approach is Dr Paul Thompson's (University of Essex) study of family life and social history in Edwardian Britain.

Monitoring

It is possible, simply by drawing the interviewers together and taking their reactions, to get an impression of the progress that has been achieved at various stages of the recording programme. However, for the effective monitoring of the project more systematic aids should be introduced. These are needed because the creation of oral history recordings usually far outstrips that of processing the recorded interviews. Cataloguing, indexing and transcribing generally lag so far behind recording that the customary aids which give access to the material are not available when they would be most useful for project control.

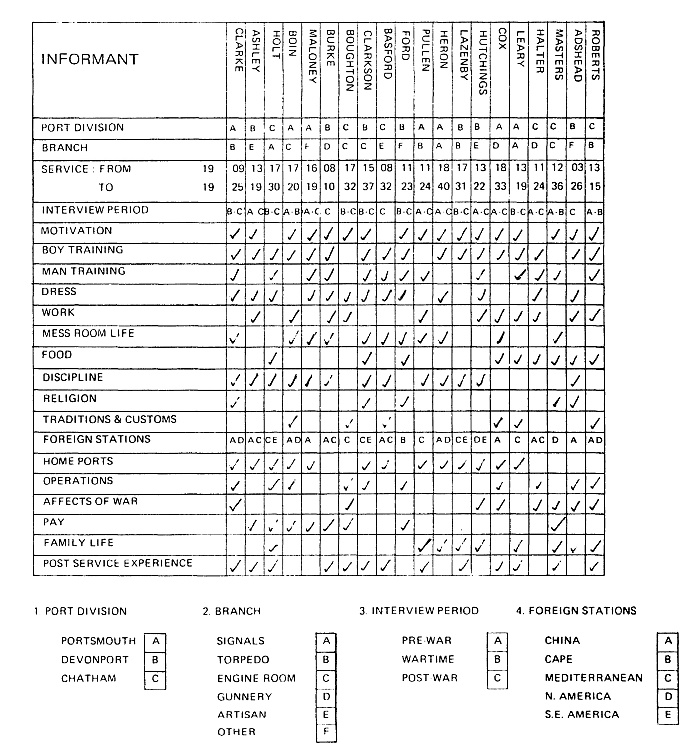

As an intermediate means of registering the project information as it is being recorded, simple visual aids can be designed which are appropriate to the work which is being carried out. In the case of the lower deck project the chart reproduced opposite was useful as such a tool. When projects are geared to preparatory research papers and control charts of the kind reproduced [under Documentation, next section] oral history recording can be effectively monitored and sensibly controlled. At the beginning of the project, the research paper represents the academic definition of the project goals. By careful application in the field academic prescription and practical possibility can begin to be reconciled. Thus, in the light of early interviewing experience, the list can be altered after some initial application. Certain questions may be modified, some removed or new questions may be introduced into the initial scheme, until a more refined and useful document emerges. Sensible alterations to the scope of a project cannot be made without a systematic approach of the kind that is implied in the formulation of a project paper.

As recording progresses, a chart of the information being collected permits the monitoring of the project's interim results. The value of the original topics - and their various divisions - should not be treated as inviolate until the work has run its full course. A common experience is that the collection of information in some subject areas reaches a point of saturation before many of the others. Such lines of questioning may be discontinued when there is reasonable certainty that their continuation would be unlikely to add significantly to the information that has already been recorded. The converse is also facilitated by a framework which permits the interim analysis of results. That is to say, areas in which the collection of information has proceeded less satisfactorily can more easily be singled out for greater attention.

Devices of the kind described above are usually essential in the effective management of oral history research. Unless the resources of the collecting centre are untypically lavish, there is usually no other means by which it can be established that the interviewing and recording is achieving the results which were originally sought. It is obviously necessary, through such methods, to be able to control the course of the project and to judge when it may be terminated.

Documentation

For the proper assessment and use of oral evidence, the collecting centre should systematically record the project methodology. Without this background information the scholar may not be able to use appropriately the information which has been recorded. What were the aims of the project organiser? By what means were informants selected for interview? What was their individual background? How were the interviews conducted? How was the work as a whole controlled? The more information there is available to answer such questions as these, the more valuable oral history materials will be to the researcher and the more securely he can make use of them in his work.

A formal paper, of the kind recommended earlier, can tell the user a great deal about how the project was structured. A working file will be even more useful, if it reveals the way in which the work evolved (recording what changes were introduced at what stage in the development of the project). Such files should be maintained and regarded as an integral part of the research materials which may be needed by historians.

Individual informant files should also be accessible for research. They should contain biographical details of the informant and also be organised in such a way that the user can correlate tapes or transcripts with places and dates which are covered by the interview. In this respect, interviewers are in a uniquely valuable position to secure a documentary basis of the information they record. Often the informant's memory, photographic and documentary materials in his possession, reference sources and the interviewer's own subject expertise, can be combined to formulate quite a detailed chronology. This will support and give background to the recorded interview.

Similarly, the interview itself should be used as a means of establishing the kind of background information that will give additional significance to the information the informant provides. Thus, in addition to the specific project information the interviewer is seeking, he can with advantage also record details of the informant's place of birth and upbringing, his family background, economic circumstances, educational attainments, occupational experiences and so on.

Much that an informant says during the course of an interview he may wish to correct, amend or amplify subsequently. No documentation system would be complete without providing him with the means so to do. The opportunity to listen to or read the completed interview often provides the informant with a considerable stimulus to add to the information which has already been recorded. Once committed to an oral history interview, most informants feel the need for historical exactitude. Collecting centres can maintain their transcripts in pristine condition, whilst also giving informants full opportunity to supplement with written notes the information they have already given, and filing such notes along with the final tapes and transcript.