7. Cataloguing and indexing (Roger Smither with Laura Kamel)

Introduction

Oral history recordings are exceptional among reference materials in that their contents are not amenable to 'browsing'. Researchers and cataloguers may 'dip' into a book or flip through a photograph album. There are, however, no real alternatives to playing a sound recording on appropriate equipment at the correct speed all the way through. It is true, of course, that an oral history transcript is as accessible as any other comparable documents, but since the audio dimension of oral history carries a significant part ,of its message adequate documentation has to be provided by way of finding aids for access to the original medium.

The documentation discussed here is, primarily, that which the archive maintains on its own premises for its own purposes, covering the entire collection. Material extracted from the central source for publication is of secondary importance in this context and will not be considered in this section. The documentation which it is normally considered essential for an archive to supply comprises a catalogue, with entries describing each separate item in the collection, and an index or several indexes in which the user may look up the topics which match his interest and be directed to items in the collection relevant to those topics. The index should be regarded more as a key to the catalogue than to the collection itself. Although the researcher who finds only one reference in the index suiting his needs may as well go directly to the item indicated, the researcher who is offered several apparently suitable recordings by the index should use the catalogue, with its description of the nature and context of the proferred items, as a means of refining his short list before progressing to listening to tapes. Provision of transcripts may help the process of refinement still further.

What information should be conveyed by the entries in this catalogue which is so central to an archive's documentation, and does there exist a proven acceptable system which would spare the archivist the task of evolving his own? The staff of an oral history archive asking these - questions will find the answers overlap. There are several extant cataloguing systems, and any or all of them repay examination; they all, naturally, also stipulate what information is to be provided. It is, however, inevitably true that most extant library cataloguing systems have been designed solely or primarily for book collections. The cataloguer of oral history recordings may find serious discrepancies between what an existing system offers and what his collection needs. Typically, a book catalogue entry looks for a title, a statement of authorship or responsibility and publication details. The cataloguer handling recorded interviews will find such labels inappropriate to his sources and, although the conventions may be forced to meet his needs, the results may please no one. The available 'standard' library package may well not provide a solution with which a conscientious archivist will be satisfied.

As people do not usually talk in the same way as they write, similar difficulties may be found in adapting established indexing or classification systems to the needs of an oral history archive. An even more serious difficulty arises because most oral history collections are set up with a specialist subject or regional emphasis. As a result they will usually be too specialised for established general systems and too generalised for existing specialist systems. For example, the Universal Decimal Classification system (UDC) covers 'the whole field of knowledge' but consequently offers little space for any specialised single interest. An archive of labour history would find that 'Labour, Work and Employment' is subsection 331 of section 33 (‘Political Economy, Economics') of UDC's primary division 3 (‘Social Sciences'). While a specialised archive would leave large portions of the classification system unused, its cataloguers and researchers would be obliged to pursue references through several digits and 'auxiliaries' to achieve a full description, a task they might find burdensome and inconvenient. Conversely, a specialist classification system, such as the Engineers' Joint Council Thesaurus of Engineering Terms, may go into too much detail to be of use in similar circumstances, besides failing to cope with the many peripheral topics about which informants may be expected to talk,

A further difficulty in indexing is implicit in the nature of the task. Whereas cataloguing may be described as the objective description of an item in a collection, indexing involves subjective evaluation of what is significant about that item. The evaluation, moreover, must attempt both to reflect a collecting organisation's own policy and to anticipate the needs of future users. The chances of finding a system evolved by a third party that will adequately meet the requirements of both archive and user are s1ender. For any or all of the above reasons, the cataloguer may be compelled to enter on the complex task of devising an indexing system for his archive from scratch.

The remarks made in the preceding paragraphs should not, of course, be read as a rejection of all the work that librarians and archivists have already done. They seek only to caution the creator of a new oral history collection against accepting that anyone has already done all the necessary work for him. Of course, if he can find an adequate extant system, he should use it. Equally, if his collection is part of a larger library or an organisation which already has an adequately functioning single system covering its other collections, he will obviously find substantial advantages in joining in as far as possible with the methods of his colleagues. This chapter may help some cataloguers to evaluate the systems they are offered and to identify those changes on which they feel they should insist. For the less fortunate, the chapter may provide a starting point for their own design work.

General Principles

The introduction has advanced various reasons why cataloguers of oral history recordings are likely to find themselves involved in at least some design work on their documentation. Such work will require a systematic, logical approach but also a degree of flexibility to cope with a changing appreciation of needs. The staff of a new archive may have little experience or clear perception of the future role and users of their collection and there is no real substitute for experience in the evolution of cataloguing and indexing systems that work well in practice rather than look well in theory. Bearing in mind the importance of avoiding at any stage the need for extensive recataloguing or re-indexing of work already done, the problem will be to make the acquisition of such experience as painless as possible.

Certain principles can be usefully applied to new oral history collections. The first and most basic is to avoid over-sophistication. Even a 'specialist' archive may find itself less specialised than its first few interview projects lead it to expect and systems designed too rigidly will look inconsistent with material later acquired. Thus, for example, a catalogue card designed specifically with military careers in mind looks odd and functions poorly when used for conscientious objectors.

A second principle is to concentrate initially on those aspects of the organisational work which are least likely to be open to revision in the light of subsequent experience. Thus first priority should be given to cataloguing which has already been described as an essentially objective or descriptive task; the second priority, to those aspects of indexing which are least likely to cause uncertainty or appear ambiguous; and those areas most open to controversy or subjectivity should be the last to be systematised. An informant's description of a visit to a coal mine by the Prince of Wales, for example, may be simply indexed under date, personality and location. The same informant's opinions on the monarchy, however, may create problems. Cataloguers could disagree as to whether the politics expressed should be indexed as 'Socialism' or 'Republicanism', while later experience of users' expectations might indicate that a single 'Political Opinions' concept would in any case be adequate. A cautious policy of 'wait and see' may save a great deal of trouble although, of course, the cataloguer cannot wait too long for fear of building up too large a backlog of work.

A third general principle for the new collection to apply is the practical determination to operate within a realistic appraisal of available resources and of likely future trends. It is essential that collecting should not press too far ahead of documentation; it is equally important that a conscientious approach to cataloguing and indexing should not hold back the growth of the collection. If resources are limited and likely to remain so, the policy for documentation must take account of those limits. A modest system effectively covering the whole collection is of more use than an ambitious system covering only a part.

Two future trends of which all collections should take note are the probability that they will wish to publish material from their central documentation files , and the possibility - increasingly likely as the necessary technology becomes more available – that they will wish to apply a measure of mechanisation or computerisation to their record keeping and information retrieval work. The two developments may well come together: computer typesetting for the relatively effortless production of printed catalogues is one of the attractions of computer-based cataloguing systems. They both also make the same demands of the cataloguer - principally, an expectation of consistency. The cataloguer anxious for the neat appearance of his work, and looking ahead to publication without expensive proofreading and correction, will consider consistency desirable in any case. The involvement of computers merely makes the desirable essential. Computers are (unless expensively programmed for flexibility) painfully literal minded. To a computer 'Royal Air Force', 'R.A.F.' and 'RAF' will be three concepts, not one. If a computer is to be asked to search or sort the information it stores, then to achieve useful results that information must be both accurate and consistent when it is first recorded. The best method of ensuring consistency is by the early evolution of a set of clear and straightforward cataloguing rules or conventions and strict adherence to those rules once established.

Accessioning

The first consideration in the organisation of a collection of oral history recordings is how best to identify them as individual units for cataloguing. The most practical approach is to treat each complete interview, regardless of length, as the unit to be catalogued. Each interview should be represented by a unique number, which can then be used to bring together or cross-refer all relevant data such as informant's personal details, the subject content of the interview, the transcript and all finding aids such as index entries.

Accession numbers should be allocated from a single consecutive series. Attempts to reflect subject groupings or other patterns of arrangement by reserving 'runs' of numbers within this series are generally counter-productive. The reserved run may be too long or too short, the subject classifications may prove difficult to define, and the usefulness of the accessions register as an immediate guide to the size of the collection is effectively destroyed.

The maintenance of an up to date accessions register should be the first priority of the cataloguing staff of the collection. The information contained in the register need not be extensive, especially if full cataloguing is not falling too far behind accessioning. It should, however, be adequate to indicate the size of the item, the date of acquisition, the source and method of acquisition (eg 'recording', 'purchase', 'exchange', etc) and the nature of the item. For example:

| Accession No | Date | Description | Source | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 000731/08 | 2/V/76 | 1903-27 Reminiscences of RN Signals Yeoman | T Wallace | Recording |

| 000732/06 | 3/V/76 | WWI Reminiscences of YAD Nurse | ME Callender | Recording |

In this table the allotted accession number 000731 identities the individual interview: 000731/08 indicates that eight reels of tape together comprise interview 731. Reference to parts of the interview may be made by adding a third element to the number. For example, an index reference to the fact that Mr Wallace talks about his service on H.MS Repulse in reel six of his eight reel interview would specify 000731/08/06.

Cataloguing

To fulfil adequately the function of principal finding aid, the catalogue should hold information of two separate but related types: identification of the item catalogued (in an oral history collection this will normally mean identification of the informant interviewed and description of the circumstances of the interview) and a summary of the contents (in the sense of subject matter) of the interview. Established rules and conventions will greatly help the cataloguer in determining how to present his information, but the details of what information to provide and what format to use, are best dictated by the expectations and resources of the collecting organisation.

These two classes of information (item identification and outline description) can be satisfactorily combined in a single piece of descriptive documentation, whatever physical form that documentation may take. Catalogue cards, computer records, loose-leaf binders and other possibilities all offer advantages and disadvantages. The archive will wish to reach its own preferred compromise between such factors as economy and refinement, durability and ease of amendment, simplicity of removal for photocopying or other reproduction and difficulty of extraction by the unauthorised.

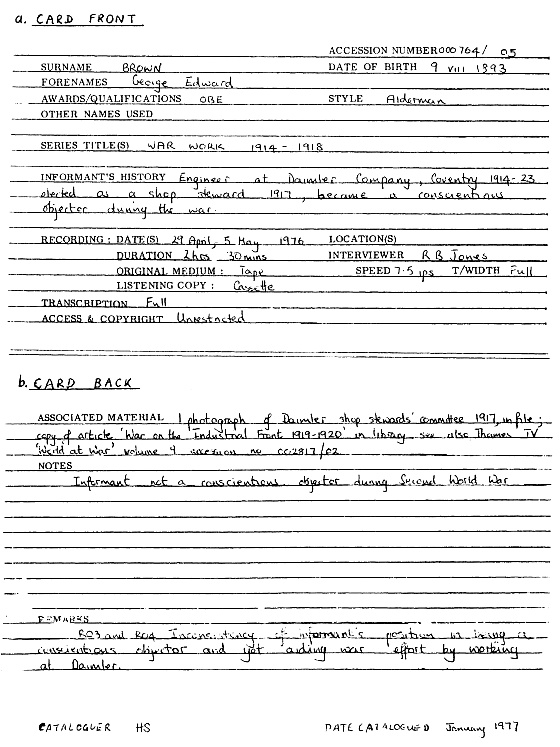

The presentation of the entry will also reflect an archive's own decisions on which elements of information are most important; how best to present information so that details often needed are easy to find; how far to reflect international descriptive standards; and so on. Reproduced [below] as an illustration (not as a model for universal adoption) is the format of a simple interview cataloguing card.

The first six lines on the front of the card identify the interview (Accession Number) and the informant (Surname, Forenames, Style, etc). An important question of principle for the cataloguer of oral history interviews is whether the catalogue entry should describe the informant as he or she was at the time the interview was recorded, as opposed to as he or she was during the period covered in the interview. Should a married woman interviewed about her single career be identified by her married or maiden name? If Daphne du Maurier were interviewed about her late husband's military career, would it be confusing to refer to her as Lady Browning? Generally speaking, the name used as a 'main entry' should be the name most appropriate to the contents of the interview and, if that criterion still leaves more than one option open, the name by which the informant wishes to be known should be preferred. All applicable alternatives should, however, be available as cross references -hence the provision for 'other names used'.

The six lines following (Series Titles, Informant's History) indicate the reasons for the informant having been interviewed. The project or series into which the interview fits is indicated; provision is made to cite more than one series title if required, as an informant's reminiscences may be relevant to more than one project. Space is also given to explain how the informant's experiences are relevant to that project. This space is left undivided, as efforts to pre-determine or tabulate 'areas of experience' will usually break down sooner or later -a format appropriate for a coal miner might not lend itself to the career of a shepherd, for example. Cataloguers would, however, be expected to establish conventions to ensure that comparable careers were described in a consistent style throughout a project. Provision of personal details about the informant and his career in the catalogue may of course be reinforced by more detailed coverage in the personal file relating to that informant which the archive will almost certainly wish to retain. The details provided in the catalogue should, however, be sufficient to indicate the topics which the researcher may expect to find in the interview.

The remainder of the front of the card describes the circumstances of the interview and its ownership. The descriptions of the information (Recording Dates, Locations, Duration, Interviewer, Original Medium etc) are largely self-explanatory, but their use is not necessarily so and serves as a reminder of the need for detailed cataloguing rules. Is the more significant date that on which recording began, or the date recording was completed? Should duration be expressed precisely or 'rounded off,' and in minutes only or in hours and minutes? What are the significant technical variables about the original recording -the type of tape (ie single, long or double play), the tape recorder and microphone used, the speed and track width of the original. If 'Listening Copy' is always available on cassette is this descriptive line redundant, or is it necessary to indicate whether or not a listening copy has yet been made? How much detail would be expected under 'Transcription' -a simple 'yes/no', or full information (Reels 1-4 and part of 5 only)? The list could be greatly extended, but the argument is obvious.

The back of the card provides space for listing 'Associated Material'. That is, material relating to the informant which is also available to users of the collection, such as diaries, photographs or letters. A section for 'Notes' allows the inclusion of additional information for which other areas of the card may not provide sufficient space or for which no other provision is made. Such information may relate to the interview (e.g. 'long break in recording owing to illness of informant') or to the informant (e.g. 'informant abandoned pacifist viewpoint on outbreak of Spanish Civil War'). The section headed 'Remarks' permits the cataloguer to record in this one area subjective comments on the interview. Such a provision will encourage the cataloguer to complete the rest of the card with proper objectivity. It also provides an extra dimension which users of the collection (properly warned of the individual and subjective nature of the comments) may find of value. For example 'surprisingly unsympathetic attitude of doctor towards shell shock' will tell the reader something about the informant which the synopsis (confined both by a restriction on length and an insistence on impartiality) could not convey.

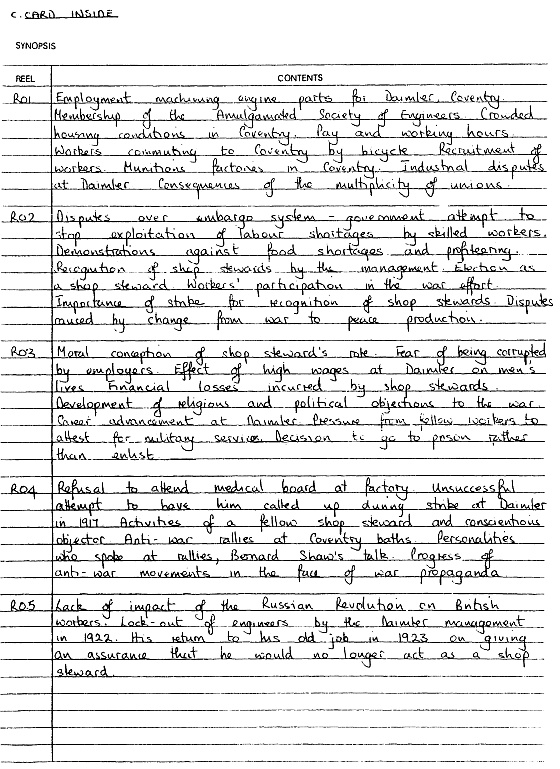

So much for the card's use to identify the item being catalogued. The second function of the cataloguing process -providing a guide to the subject content of the recording -is fulfilled by the synopsis on the inside of the catalogue card. The synopsis must be quite detailed or it will not provide potential users with as clear an idea as possible of the relevance of the recording to their interests. At the same time it must not be over-lengthy or the catalogue ceases to be an easily used research tool. The Museum's experience suggests that 50-75 words for each 30 minutes of recording strikes a reasonable balance. To compress the information contained in an interview into this number of words, and at the same time to reflect accurately the sequence or pattern of the interview, confronts cataloguers with quite an exacting task.

The synopsis should take the form of a list of the significant subjects mentioned, reflecting the order in which information appears on the tape. If an informant reverts to a topic mentioned earlier the recurrence should be noted, not deemed to have been adequately covered by the first mention. Within the limits of permitted length the synopsis should be easy to read - excessive contraction of phrases or clauses can be counter-productive. Information should also be complete: the phrase 'opinion of comfortable life lived by Italian POWs employed as farm labourers' is of considerably less use than 'resentment of comfortable life ...' The Museum's instructions to cataloguers suggest the following types of information are desirable for inclusion in a synopsis.

- Locations and dates of events wherever possible, eg 'Commission to paint and draw in Northern Ireland 1965'.

- Descriptions of events and activities, eg 'Work of wiring parties in erecting and repairing wire fortifications in no-man's land'.

- Opinions and attitudes expressed by the informant eg 'Amazement at number of pacifists' .

- Opinions the informant heard expressed about himself or others eg 'Father's hostility to her taking up nursing'.

- Illustrative stores and anecdotes, eg 'A friend losing her hand in an accident at Woolwich Arsenal' ,

- Personal recollections about other people eg 'Development of the air 'ace' concept and comments on Major T B McCudden, Captain A Ball and Captain W A Bishop'.

- Descriptions of pieces of equipment and practical experiences of using them eg 'Listening devices used for sound ranging in France during 1918. Description of microphones in use. Locating enemy guns by cross referencing signals from six points'.

Indexing

The most refined catalogue imaginable will, in spite of its inherent quality, be only as good as is permitted by the accessibility of the information it contains. A poorly indexed catalogue is, therefore, automatically a poor catalogue. This section considers the question of accessibility.

An archive using a card based catalogue will probably be restricted to a single copy catalogue, available in only one order. An , organisation using a loose-leaf (paper) catalogue, could fulfil several 'indexing' functions by producing extra copies of the catalogue sorted by different priorities. (This option is, of course, also available with card catalogues, but only if quantities of typing and clerical assistance, usually not available to new collections, are to hand). If restricted to a single copy catalogue, the archive should maintain that catalogue in accession number order. It is true that this removes the possibility of using the catalogue in any self-indexing capacity, but the accession number is the most available, logical and incontrovertable label identifying an interview for the purposes of all references to it. A file in alphabetical order of informants' names is the next most useful tool, but never as a sole course. Remember that ultimately references would be not just 'SEE SMITH' or 'SEE SMITH, JOHN' but potentially 'SEE SMITH, JOHN (Accession Number XXXXXX)' to achieve positive identification. A decision on the importance of other aspects of the informant or the interview circumstances for indexing purposes would have to be taken by the individual archive. If its work is built around interview projects, lists of the interviews relating to each project are obviously essential; a collection serving regional interests may also feel a need for an index by informant's home-town, and so on. The bulk of indexing work, however, will lie in providing access to the subjects covered in an interview.

If the circumstances of the archive permit, the work of subject-indexing should be carried out at the same time as the writing of the catalogue synopsis and by the same cataloguer. Not merely is the possibility of actual error or mistaken emphasis then reduced compared, say, to a practice of employing an independent indexer working only from the synopsis, but the cataloguer may use the index to supplement the information in the catalogue. If an informant, for example, has spoken of the qualities of Hurricane, Typhoon and Tempest aircraft, the cataloguer may for the sake of brevity be able only to write in the synopsis 'Good qualities of Hawker aircraft' while the index could refer to each machine individually.

The archive must decide how far its resources permit it to be helpful to its user. In the first place, it must decide how accurately to locate each reference; whether to the correct interview, to the correct reel of the interview, or to a precise, measured or timed location on that reel. If synopses have been written reflecting reasonably the order of items on each reel, the second suggestion is probably the best compromise. If interviews tend to be short in a given collection (say an hour or less) even a reference simply to the interview may suffice.

Next, a decision must be reached on how much information to convey in each index entry. That is, should a reference consist merely of a keyword or a UDC code linked to an interview number (as the index at the back of a book merely links topics to page number) or should it incorporate a brief, descriptive statement. In a strict sense, when the index exists as a guide to the catalogue, the former approach should be adequate, while the latter requires extra effort. On the other hand, the latter approach does reduce the labour involved in discovering appropriate references if the keyword or classification selected offers a multitude of possible citations. If a user were researching food supply in the trenches in the First World War in an archive with much material on army life throughout the twentieth century, consider the varying degrees of usefulness to him of the following three types of heading for a reference to a particular reel:

- 355.65 (this is the UDC code for 'Military Administration: catering, feeding, rations, messing')

- RATIONS, ARMY

- RATIONS, ARMY

1917, Passchendaele Ridge: irregular supply and terrible condition; effects on men's health and morale.

If an archive has the resources, the last example is likely to be the most popular with researchers, although the extra effort required is far from negligible.

The most important decision to be taken in subject indexing is, of course, what kinds of information to select for indexing and how to label them. It is, to begin with, extremely desirable that the indexing staff should have a knowledge of the subject matter covered by the interview and an understanding of the intentions of the interviewer (and of the archive) in making the recording. Without such knowledge, a cataloguer may be liable to miss, or misinterpret, the significance of a point covered in the interview. Staff should also understand absolutely what constitutes useful coverage of a topic in oral history, and what does not. A brief or passing reference is only useful if the fact related is of particular interest; opinions or arguments unsubstantiated by evidence or example are similarly only of occasional value; second-hand information may be too unreliable to merit indexing, but if of special interest may be recorded with suitable qualification. It is above all the informant's own experiences, his own recollections of events, and his own attitudes and opinions that interest the oral historian and that should be reflected in indexing.

Once the subjects to be indexed have been chosen, the next step is the allocation of appropriate subject headings or keywords. If the archive is using an extant classification system, the problem must be one of detailed selection. For example, does an informant talking about government direction of agriculture in war time constitute, in UDC Terms, 351.778.2 ('Public Health, Food, Housing Etc/Food Supplies, Housing/Food Supplies, Household Goods') or 351.823.1 ('Economic Legislation and Control, Agriculture, Trade and Industry/Extractive Industries/Agriculture, Stockbreeding, Hun ting, Fishing') or 355.241 ('Forces (Service) Personnel, Mobilization etc/Mobilization of the whole Nation, Economic Mobilization/Agriculture, Industry, Manpower')? If the archive is using its own classification system the problem may be still more complex, for the appropriate classification may have to be devised and not merely selected.

Some types of indexing present few problems, and (as suggested earlier) it may well repay a new archive to concentrate its indexing activities at first on such areas. These types are, generally speaking, those where identification is positive and labelling amenable to broadly accepted rules or usages eg places, personalities, events (arranged by date) and equipment. Provided agreement is reached on which conventions or textbooks are to be regarded as authoritative, sections of a subject index covering areas such as these may be left to grow virtually unsupervised.

The classifier's real difficulties begin with those rare areas of subject matter not amenable to concrete definition; that is, areas of abstract or conceptual information which are, of course, bound to figure largely in the personal opinions and reminiscences which interviews elicit. The problems may be reduced if both index user and index compiler are encouraged to visualise even the conceptual in as concrete a manner as possible. If an enquiry can be turned from a hazy 'I am interested in medical advances' to a more solid 'I would like to find a description of an early blood transfusion' -and if indexing is arranged to cater for such enquiries - then everybody's life becomes considerably easier. The quantity of conceptual work, however, can only be reduced in this way, not eliminated, and will continue to present two main problems. The first is the question of the level of detail at which the index should seek to work: should, for exam pie, an expression of anti-semitic opinions by a Nazi sympathiser be indexed as 'Politics' or 'Fascist Politics' or 'National Socialism', or should the approach be 'Racialism' or 'Anti-Semitism '? The second major problem which is bound up with the first is that of establishing a controlled vocabulary for the conceptual index.

To ensure that a common vocabulary is shared by all its indexers (and by users) an archive must expect to produce, sooner or later, some kind of guide to its index. Part of the guide's function is purely linguistic - establishing 'preferred' terminology among synonyms (eg referring users from 'CALL UP' or 'DRAFT' to the preferred terms 'CONSCRIPTION'). The remaining part of the guide's job is to explain the classification hierarchies used by an index, so that a researcher may have explained to him the relationship between general and detailed terms (reminded, for example, that an interest in 'PREVENTIVE MEDICINE' may be furthered by exploring 'VACCINATION', 'MASS X-RAY PROGRAMMES', etc) and be guided between terms at the same level of detail (eg be informed on looking up 'BLACK MARKET' that the index also has a term covering 'SMUGGLING'). If an adequate guide exists, the question of selecting the appropriate level of detail when making an index entry becomes less severe as the intelligent user of the index will find his own way through the hierarchies.

The nature of the collection, in any case, will probably suggest an appropriate level of detail for indexing. If an ex-soldier interviewed by a military museum refers briefly to his pre-conscription work as a footman , or an ex-footman interviewed by a social history archive refers briefly to his military service, the two organisations would probably feel that, respectively, 'DOMESTIC SERVICE' and 'MILITARY SERVICE' were the most detail their users would expect of them. In their own areas of specialisation, however, they would naturally wish to go into much greater detail. Even in those areas that appear to require detailed attention, however, it may be possible to save time on indexing if the appropriate information is readily accessible elsewhere. If an archive carries out its interviews in subject groups or projects, and each project is well catalogued, a user with broad interests that lie within a particular project's terms is likely to find the items that interest him as quickly by reading the catalogue entries for that project as by hunting through an index. There are, of course, dangers for both user and archive in relying too heavily on this short-cut; a researcher interested in the miners' strike of 1974, for example, should not expect to find all his material in interviews with miners, although he would find a great deal of it there.

The archive must also decide what arrangement of its subject indexes will most help its users, choosing between a combined alphabetical list (on the model of a dictionary) -which should help the general browser, but will frustrate the specialist by forcing him to refer back and forth -and a structured classified list (on the model of a thesaurus) -which should help the specialist, but will frustrate the researcher whose interests cross the borders of the classifications used by the index. As both systems have their advantages, an archive may attempt to provide both to a degree, by adopting one for use and reflecting the other in its vocabulary guide. In weighing advantage against disadvantage, however -as so often in this chapter the ultimate decision must be taken by the individual archive, in the light of its own circumstances, needs and experience.