Problems of selection in research sound archives (Rolf Schuursma)

An archivist is usually the opposite of a selectionist….

This was the first sentence of a paper, which I presented to the Annual Conference of IASA in Jerusalem in 1974 (Phonographic Bulletin, No. 11, May 1975, P.12-19). The paper was called “Principles of Selection in Sound Archives” and it is perhaps symptomatic that the focal point of the present contribution has moved from principles to problems. Since 1974 I have been involved in various efforts to cope with the ever growing amount of sound and film records in the Netherlands, and again and again the term “selection” has appeared as a kind of incantation - a miraculous keyword - which should open the road to archival happiness. In fact, selection means a lot of problems, which mainly have to do with a lack of funds and, most particularly, with a lack of staff. This paper does not attempt to provide the final solution to our troubles. It is meant as a stimulus for discussion and a starting point for critical questioning about archival policy. It is primarily restricted to the problems of spoken word collections, but some observations might also refer to archives of music recordings, and even film and TV archives could easily recognize some of their own deliberations and solutions.

This paper will summarize statements made in the 1974 conference about selection criteria, and the then draw attention to the process of selection and the effectiveness of selection.

In the context of the paper, ‘record’ means the carrier, including the audio-information. ‘Recording’ means just the audio-information itself. So a gramophone record or an audio tape is a ‘record’, containing for example a ‘recording’ of an interview with Bela Bártok or a performance of one of his string quartets.

Why Selection?

To reiterate: an archivist is usually the opposite of an individual who makes selections. By nature the archivist is striving for an ever-growing collection; including whatever he can get; excluding as little as possible. Why should he then apply selection to the collection of recordings ready to enter his vaults? There could be three possible reasons:

-

Lack of space

New technical developments will eventually allow smaller formats for records, yet space will always be an argument in favour of selection. Audio-records also demand certain standards of air-conditioning which may involve a considerable investment of money. -

Lack of staff and equipment for preservation

Preservation may consist only of keeping air-conditioning under control and a regular check on the stability of the records in storage. But old and deteriorating records have to be copied, involving time-consuming operations, sophisticated equipment and a quantity of blank carriers. -

Lack of staff for cataloguing

The accessibility of the recordings in our archives is of course very much dependent on the quality of the catalogues we are going to produce. Even a simple catalogue of audio recordings should be based upon standardized title descriptions. For example, the ISBD, while spoken word recordings demand an additional summary of the contents. The descriptions should be classified according to some system using keywords derived from an authority file such as the one produced by the Library of Congress. Cataloguing is, therefore, a time-consuming affair.

Selection should be seen as a means to diminish investments, exploitation costs and above all the considerable costs of staff necessary for preservation and cataloguing.

Criteria For Selection

The term selection implies a procedure based on the general policy of the archive and certain criteria within the limits of the policy. What criteria can we establish without hampering future research and destroying recordings which, in a hundred years or more, could have become interesting or even indispensable? Are there methods to avoid disaster and to protect ourselves from blame by our successors? It is doubtful whether such criteria can be found but we should try to formulate a few points which can be applied without too much risk. Apart from obvious things like the discarding of dubbings or recordings of very bad quality, the following should be taken into account when an archive begins to define selection criteria.

-

The specific qualities of the medium

Sound archives are collecting music and spoken recordings or are concentrating on one of the many other fields. Spoken word can, of course, also be preserved in writing or in print. It is, however, not really possible to convey on paper variations in tone, laughter, sighs, chuckles, interruptions and intervals-in short, non-verbal expressions. This does not mean that one has to preserve every recording of spoken word. We should restrict ourselves to records, which contain medium-specific information. So many recordings of speeches by official persons, made entirely in accordance with the policy of their government, are in fact second-rate sources which do not add significantly to the knowledge stored in traditional archives of written and printed records.All of this means that we should concentrate on recordings made without previous preparation such as live-interviews, discussions and improvised talks; in other words, recordings, which enrich already existing, printed reports in the daily papers and official documents.

Medium- specific qualities apply also to music recordings, since such recordings cannot be replaced by printed music in any way. Thus the first criterion will seldom apply to music, because it is by nature medium-specific and irreplaceable.

-

The division of work between archives

Most spoken word archives are in fact specialized institutions, concentrating on restricted fields, and usually there is only a small overlap with other institutions. If there is duplication, as is sometimes the case with broadcast sound archives and research archives outside the radio, it is there because radio archives are not able to provide a service outside their broadcasting institutions. However, the general policy of archives should be very clear about the limitations of their own collection as well as others and selection policy should take account of these limitations. This applies equally to spoken word and music.

-

The length and completeness of recordings

Selection has also to do with the length and completeness of recordings. This does not mean that only extensive and complete records are valuable, because a very short abstract from an early broadcast may be worth many long recordings of later date. In the case of spoken word it is particularly difficult to decide to what extent fragmentary recordings are useful. News broadcasts, for instance, which are transmitted by the dozen every day, usually consist of many comments and few authentic sounds. They are useless for research and for most educational applications. On the other hand complete recordings of live interviews belong to the more important part of every archives collection and must certainly not be eliminated because of a too strict selection policy. In the case of music, complete recordings are preferable in most cases.

The above-mentioned points give us something upon which to base a policy. In short: are our recordings adding to the traditional written media or are they worthwhile because of their specific qualities as sound records? Are they held elsewhere in the country or abroad, or are they too short and too fragmentary to provide useful information? Criteria along these lines will in general not impede any future research.

There are a few additional points, which are more risky, but can do little harm to our descendants in the world of sound archives.

4. Single records or complete collections

Most records, be they spoken word or music, belong to series or to collections brought together with a specific aim. In many cases records derive their importance from the mere fact that they belong to a collection, while single records without any relation to other recordings stand apart and may be less valuable. The recording of a well known Haydn Symphony by a certain orchestra under a particular director is of course different from the same symphony recorded as part of the complete series by Antal Dorati and the Philharmonia Hungarica.

5. The importance of the subject: estimation of value

Frequently spoken word recordings have been made because at the time people seemed to be interested in the subject. Radio broadcasts, in particular, tend to be of temporal value, fashionable or tied up with sudden bursts of sensational curiosity. Archivists should be able after some time to distinguish between temporal and more enduring subjects. There are risks in this approach, because any tape may contain the one and only recording which eventually proves to be of outstanding value but, as long as we deem selection to be necessary, the subject-criterion provides another weapon against pollution of our precious collections. Archivists of music recordings may easily find parallels within their field of interest.

6. The importance of the subject: social history

There is a tendency to apply social sciences and historical research to daily life, the life of the man in the street, the unemployed, workers in factories or minorities in great cities. Aside from the inevitable exaggeration of this movement, it is nowadays a matter of common understanding that historians and archivists have spent too much time on outstanding events and very important persons, and that they should change their course. While a lot of documents cover the dealings of the so-called establishment, the number of records related to the circumstances of living and the cultural interests of the public at large is relatively small. Selection should take care of this distinction and place less value on outstanding persons and more on social history, at the cost of our customary collections of voice portraits of VIP’s, who as a mater of fact are well prepared for eternal life anyway.

Further to this summary of the criteria of selection in general terms, it should be indicated that for each specific subject of research, whether music or one of the many fields of spoken word, the archivist may develop his own criteria within general parameters, dependent upon the policy of the archive and the point of view within that field research. However, it is not easy to use more specific criteria without grave risks of the wrong kind of perfectionism. General directives and a well-developed common sense are better remedies than so-called scientific criteria which, in practice, spoil much of the fun of collecting and do not really add to a well-balanced archive collection.

The Selection Process

Before moving on to the process of selection, a few preliminary explanations are required. It should be stressed that this paper has to do with spoken word, although it may also apply to music. Also, the figures used by way of explanation about the effectiveness of selection are based upon both experience and speculation. If they have any significance it is because they may stimulate the discussion and provide a kind of model for calculating. Lastly, the article is restricted to matters of personnel, not investments and costs in the material sphere, because the costs of equipment and materials are usually far less forbidding than the costs involved in hiring staff.

Finally the selection process has been related to the cataloguing. Records which have been selected for further use will, in any case, pass through the cataloguing process in order to become accessible. It is, however, doubtful if all of them will also go through a stage of copying and further preservation. After passing the selection process many recordings will indeed return to storage without further preservation. Including preservation in this calculation model would complicate things unnecessarily.

The selection process consists of a series of actions which lead to the decision to send the collection or the single record for further processing through the archive (positive selection), or to exclude it from further processing or even to destroy it (negative selection). Within that kind of process there are many possibilities, differing in degree of intensity relative to the needs of the archive and the kind of input of records in the archive. At one end of the scale we find coarse-mesh selection, and at the other end fine-mesh selection. Coarse-mesh selection is the evaluation of complete collections of recordings without going into each record specifically. Fine-mesh selection is based upon a record-for-record approach necessary, for instance, in case of probable copying, bad technical quality, etc.

In the first case the selection process is usually not very time consuming, which means that the ratio of the size of the collection and the time spent on selection is advantageous for the archive. However, coarse-mesh selection is risky whenever the collection is not already well defined and well documented. If this is not the case, one may end up with a lot of rubbish and a few really valuable recordings.

In considering fine-mesh selection it is worthwhile to go into the question of effectiveness of selection in more detail. The process of selection with a fine-mesh approach consists of several stages:

- Getting the record from storage;

- Inspecting the container, the sleeve, the label and the eventual documentation with the record;

- Listening to the complete record or to part of it, and/or studying an eventual detailed list of items of the recording;

- Filling in a selection-form with headings for a few primary dates;

- Sending the records back to storage;

- Evaluating the findings and taking a decision about positive or negative selection. Completing the selection form.

Stages 1 through 5 can be described as a pre-cataloguing process because, in the case of positive selection, the selection-form can, amongst other things, serve as a tool for cataloguing proper.

Selection of Different Records

Let us compare a few imaginary records of ten-, thirty- and sixty-minutes duration by running them through the selection stages mentioned above and estimating the time taken for each stage. In doing this we can also make a distinction between a selection process in which the record is listened to completely, for instance in the case of dubious dubbings or a great many separate items (maximum intensity), and a process in which only part of the record is listened to (minimum intensity). See Table1.

|

Duration of recordings |

10m |

30m |

60m |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stages of the selection process | min. | max. | min. | max. | min. | max. |

| 1. from storage | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m |

| 2. inspection | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m |

| 3. listening | 5m | 10m | 10m | 30m | 20m | 60m |

| 4. filling in form | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m |

| 5. to storage | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m | 3m |

| 6. evaluation and completing from | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m | 5m |

| Total of selection process | 26m | 31m | 31m | 51m | 41m | 81 |

Table1: stages and durations of two different selection processes for recordings of three different durations (in minutes)

It is not insignificant that the only variable figures in this table concern the time necessary for a minimum or maximum listening to the recording. All other figures are, generally speaking, the same for every kind of record. (The storage time has been limited to three minutes each because one should, of course, handle a group of records all in one.) There may be some differences between the one and the other single recording, but such variations are not significant for our comparison. It must be noted, however, that part of the pre-cataloguing process does not have to be repeated during the cataloguing process proper. We should, therefore, deduct some time from the total duration of the selection process in order to make a comparison with the cataloguing process more meaningful. But a suitable cataloguing process should include the listening stage, particularly in view of the production of a summary and the determination of keywords. Only a few data listed on the selection form might then serve to speed up the cataloguing process and you cannot subtract more than five minutes on the average from each of the total times mentioned in the table.

We may, in any, case safely conclude that

if selection does not result in the de-selection of a certain number of records, it will only add considerable additional loss of time to the existing lack of time of the staff.

The duration of the selection may very from twenty to eighty minutes or more per record, depending upon the duration of the recording and the amount of listening we decide to do.

The Cataloguing Process

In order to underline the point, let us take a close look at the cataloguing process and list the stages involved in the process with their estimated durations (a simplified reproduction of the total process). See Table 2.

|

Duration of recordings |

10m | 30m | 60m |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Stages of the cataloguing process |

|||

| 1. from storage | 3m | 3m | 3m |

| 2. standardized title description (the complete process) | 45m | 45m | 45m |

| 3. summary | 20m | 30m | 45m |

| 4. subject-code and keywords | 15m | 15m | 15m |

| 5. input in database | 10m | 10m | 10m |

| 6. to storage | 3m | 3m | 3m |

| Total of cataloguing process | 96m | 106m | 121m |

Table 2: Stages and duration of the cataloguing process for recordings of three different durations (in minutes).

Here also there is a relationship between the duration of the recording and the total duration of the process. The variable is in the summary stage which varies according to the duration of the recording because a longer recording will usually be more time consuming than a shorter one.

In comparison with the cataloguing process, selection takes a lot of time. If we put together the minimum selection figures table 1 and the cataloguing figures from table 2 and subtract five minutes from the pre-cataloguing phase, Table 3 applies.

|

Duration of recordings |

10m |

30m |

60m |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. selection (minimum intensity) |

21m |

26m |

36m |

|

2. cataloguing |

96m |

106m |

121m |

|

Total time taken |

117m |

132m |

157m |

Table 3: duration of selection and cataloguing for recordings of three different durations (in minutes).

To make the comparison work for a group of records ready for a fine-mesh selection process followed by the cataloguing process, let us take a group of one hundred records with an average duration of 30m per recording (resulting in 26m for minimum selection and 106m for cataloguing). Consider that the records pass the selection with flying colours, so that all of them get catalogued in the end. The total duration of processing these records through selection (minimum intensity) and cataloguing would then amount to the following: see Table 4.

| Number of recordings | 100 |

| Average duration of recording | 30m |

| Selection (minimum intensity) | 43h 20m |

| Cataloguing | 176h 40m |

| Total time taken | 220 h |

Table 4: duration of the selection and cataloguing processes for 100 recordings of thirty minutes average duration (in hours).

One person, working effectively seven hours per day, would thus spend more than six days on selection and more than twenty-five days on cataloguing those hundred records.

In this case the selection process, seen from the point-of-view of the selecting archivist, was entirely without result. But when does selection become effective? In other words: where is the break-even figure at which it is to the advantage of the archive to process records through the selection procedure and above which selection is a waste of time, indeed only adding to the problems of the archive?

The Break-even Point

Take the following supposition:

As long as we succeed in keeping the total time involved in the selection and cataloguing of a certain number of records equal to the time which would have been used for cataloguing without previous selection, there is an advantage for the archive.

Even if we do not win time during the selection and cataloguing processes, we will have less to store and eventually less to preserve. And we are not losing any time by selecting carefully.

However, if we succeed in making the total time involved in selection and cataloguing less than the time originally involved in cataloguing proper without previous selection, then selection becomes even more advantageous. But as soon as selection and cataloguing time add up to a total higher than the cataloguing time without previous selection, we pass the break-even point in the wrong direction. Then the archivist should decide whether problems of space and preservation might counter-balance the loss in time on the selection/cataloguing side.

Now what does the break-even point mean in the case of our hundred records? Taking the figure of 176h 40m involved in the cataloguing of those records (again: 30m average duration, 106m cataloguing per record), if we are going to put those 100 records through the selection process and if we are only going to catalogue the records which were positively selected, we should nevertheless stay within the limit of those 176h 40m in order not to lose time. To find the break-even point in this case becomes a very easy procedure.

We have to go through the selection process anyway for all hundred records. As we have seen this process takes up 43h 20m (again: 30m average duration which means 26m selection per record). Now we only have to subtract those 43h 20m from the 176h 40m mentioned above to find the time which we can safely use for cataloguing proper.

Thus we have 133h 20m left for cataloguing. As long as we stick to 106 minutes per record for the cataloguing of each of these 100 records, we are then able to catalogue about 75 records without going beyond the break-even point. In other words:

There is a break-even point below which it is even more advantageous to select and above which the archive may lose extra time by selection. The break-even point can be found when one subtracts the time involved with the selection process from the total time, which would have been involved with cataloguing all records, in question if there had been no selection. The remaining time is left for cataloguing and should be divided by the time necessary for each separate record in order to find the total number of records, which can safely be considered for cataloguing.

An archivist should in this case instruct his staff to de-select at least one quarter of the pile of one hundred records in order to make the selection a useful tool in the process of saving staff time and money. This assumption is based upon a selection process with minimum intensity. More intensity means a deteriorating ratio, which may even go beyond fifty-fifty.

100 audio-recordings of different duration – fine-mesh selection with different intensity

|

Average duration of recordings |

10m |

30m |

60m |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity of selection | min. | max. | min. | max. | min. | max. |

| Total duration of cataloguing if no selection |

160h |

176h 40m |

201h 40m |

|||

| Total duration of selection minus pre-cataloguing phase | 35h | 43h 20m | 43h 20m | 76h 40m | 60h | 126h 40m |

| Total time available for cataloguing after selection | 125h | 133h 20m | 133h 20m | 100h | 141h 40m | 75h |

| Duration of cataloguing per record |

1hr 40m |

1hr 45m |

2h 1m |

|||

| Number( = percentage) of records to be selected for cataloguing | 78 | 73 | 75 | 57 | 70 | 37 |

| Number ( = percentage) of records to be de-selected | 22 | 27 | 25 | 43 | 30 | 63 |

Table 5: calculation of the minimum percentages of audio-recordings of different duration to be de-selected in a fine-mesh selection process of two different intensities, in order to prevent extra loss of time because of selection.

A greater percentage of de-selected records is more advantageous to the archive in terms of timesaving. A lesser percentage means greater loss of time and makes selection disadvantageous in terms of timesaving.

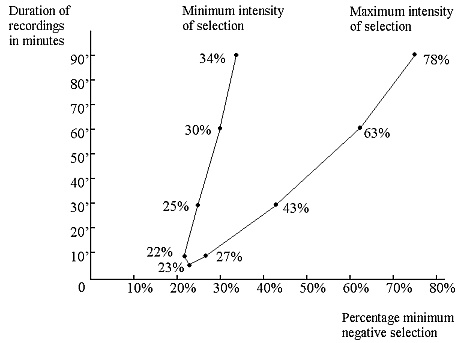

Table 6: minimum negative selection with recordings of different duration

Conclusion

The purpose of this exercise in sound archive arithmetic is, of course, not to deliver a ready-made calculation model for all kinds of selection. It is, at best, a clue to the solution for a small part of the total selection problem. Establishing reliable and effective criteria is probably a much more difficult problem to solve.

However, to get back to the beginning of the paper, it is important for any archive to establish the general policy with regard to the limits of its collection. Only when it is apparent that, even within those limits, the archive simply cannot cope with the amounts of records pouring in, it should consider a more energetic selection procedure. Even then, it is better to try a kind of coarse-mesh selection in order to lose as little time as possible on that stage of the total processing of records through the archive.

If, however, records enter the archive without any cohesion amongst themselves or without any connection with the collection already present, it is necessary to apply a fine-mesh selection. In this case, it is advisable to consider the ratio between the time necessary for selection and the time involved in further processing through the archive including the cataloguing process. A fine-mesh selection, which does not result in at least one quarter of the records being thrown out, can eventually end in a bad result in terms of costly hours. See table 6.

One final consideration. Negative selection does not always have to end with the destruction of the records. If space is no problem, one can, of course, store them in some part of the archive where they can do the least harm. One can also offer them to another archive. However, sometime it is definitely better to pull oneself together and have the records either thrown out or destroyed. If some archivists here or there still believes in miracles, the author is the last one to attempt to awaken them from their dreams. However, we can be very certain that the longer we wait, the less money will be available and the more our conscience will bother us. A well-established selection policy, consistently carried out, is the best solution.

Rolf Schuursma was the librarian of the Erasmus University, Rotterdam.

This paper was given at the IASA conference in Budapest in 1981.